Module 16: Wildfire and Your Woodland

Introduction

Fire has existed on earth since the firstvolcano erupted close to a fuel source, and since the firstbolt of lightning struck and lit organic matter. No human was there to marvel or tremble at the sight, but fie has since become central to human existence on earth.

Fire has always been a natural part of the Nova Scotia landscape. At one time it burned where it wished, completely out of any human control. It shaped the forests and grassy plains, both destroying and creating wildlife habitat. Fire shaped new ecosystems, released carbon into the atmosphere, and may have caused changes in climate.

It burned at regular intervals, raging through forests until fuel was exhausted or rain dampened its progress. The presence of high winds often led to trees being blown down. These trees died and eventually became dry, and fuel accumulated over the decades. A lightning strike in the right place was all that was needed to heat the fuel to a flash point and start a wildfire.

First peoples skillfully adapted fie for human use. Besides providing warmth and cooking heat, fie was used to harden wood hunting tools. It could also be used to drive game from one place to another for better hunting, and even to renew berry crops. Fire also provided a measure of security at night and a centre for social interaction.

European immigrants brought a profound change in the use of fie and the ways it could be used to shape the landscape. Small coastal settlements in the early 1600s likely employed fie to clear adjacent forestland for agriculture, and many of these fires probably burned out of control, extending many kilometres into the interior of the province.

The granting of land by European interests intensified the use of fe in Nova Scotia’s forests. Often the conditional granting of land carried with it the necessity to clear large acreages for agriculture, or improvements, and one of the quickest and least labour-intensive methods was simply to set fie to the forest. Charred stumps could be pulled more easily, and crops could be planted in the open areas.

Such burning was not without its hazards. Fires easily got out of control and entire settlements were burned to the ground. Dwellings and farm buildings in the path of such wildfires had little chance of survival.

The 20th century brought enormous leaps in technology, not only for mastering the use of fie but also in controlling fie in the forest. Purpose-built tanker trucks, water pumps, and earth-moving equipment were developed to combat forest fies that raged across the landscapes of the province.

Fire towers were built in the early years of the 20th century to detect wildfires and were a common sight in many areas of the province. After World War II, aircraft were employed to both spot and control wildfies, and this use of aircraft continues today. Examples of efficient modern water bombers are found worldwide.

As can be imagined, effectively suppressing wildfire is expensive. Costs of fighting Nova Scotia wildfires exceed $4 million annually.

Why Protect Your Woodland from Wildfire?

As a woodland owner, you have values that are associated with your forested property. Perhaps you value your timber resources as one of the most important reasons for owning woodland. You may also consider wildlife and their habitat to be a primary motivation for managing your woodland. Recreation, in the form of walking, riding, or hunting, could be an important value to you. Or perhaps you relish the opportunity to visit your woodland just to get away from the bustle of everyday life. No two landowners are alike and your ownership values are unique because they are yours.

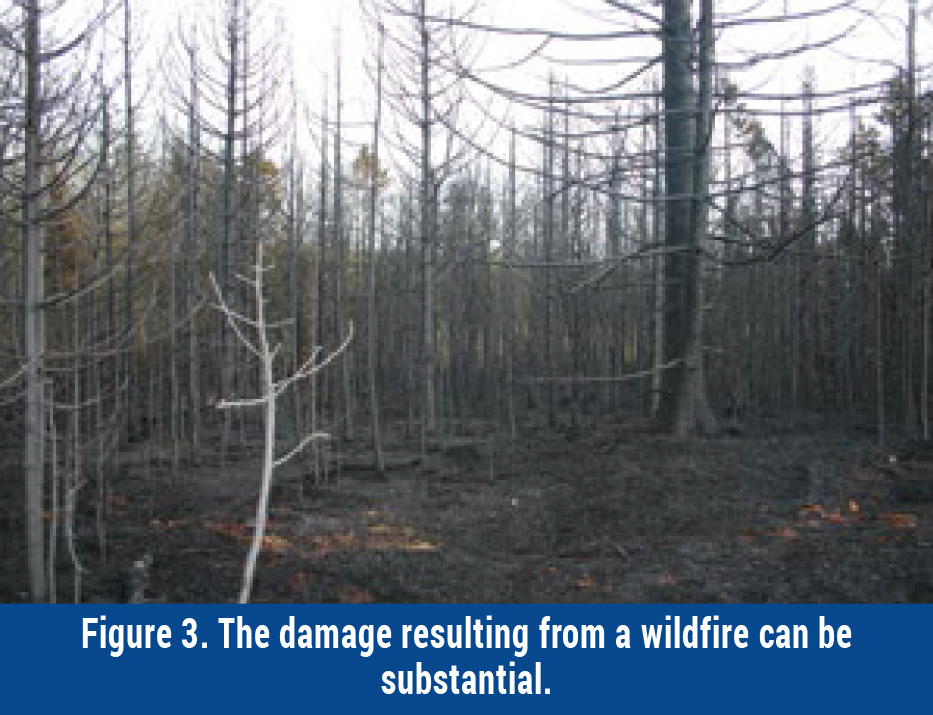

One thing is certain: A wildfire can, in a few short hours, affect your woodland in ways that may cause you to change your values and the ways in which you manage and use your woodland. Preventing wildfire is the easiest way to manage wildfire on your woodland. For this reason, it’s important to understand how wildfires may start and spread.

This module will help you, the woodland owner, to learn how to prevent wildfies on your property, and what to do if a wildfie starts despite your best preventive measures. While fie departments and Department of Natural Resources staff excel in fighting woodland fes, this module will also outline the steps you should take until fiefighters arrie, including fightin small fies on your own.

Lesson 1 - Planning for Prevention

Planning for Prevention

Preventing wildfires is everyone’s responsibility. The old saying “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” is particularly applicable to wildfire prevention. It is clear that the ways in which we behave and interact with the forest will determine whether woodland fires result. If a fire does start and gets beyond our control, we must work with emergency response agencies—including fire departments and government—to reduce the chances of it spreading. But we never wish to reach this stage! Instead, we should plan to prevent wildfires. In doing so, we can avoid the necessity of expensive firefighting efforts and potentially devastating consequences.

Prudent Planning is Effective Prevention

As the owner of woodland, you have the responsibility of preventing and controlling fires on your property. Should a fire escape to an adjacent property and cause damage, you could be liable for repairing or paying for the resulting damages. Loss of trees and woodland use due to wildfire may be serious but loss of buildings and equipment can be worse.

Every woodland owner should adequately plan and actively employ reasonable precautions against fire. This includes scheduling woods work outside the times when risk of fire is high to prevent the ignition of fires and having the proper tools necessary to control a fire should one begin. Everyone working on or using your woodland property in any way, including for recreation, should have your permission and knowledge of what to do if a fire escapes.

For example, planning safe campfires is often overlooked by many people who enjoy the outdoors. The following diagram illustrates the precautions which must be taken around campfires. It can be used as a planning tool to help prevent your campfires from becoming wildfires.

As you plan for wildfire prevention, you should consider the following actions that will greatly enhance your ability to not only prevent wildfires but also encourage early wildfire suppression on your woodland:

• Maintain a daily log of your activities, including the fire weather index, and plan your woodland management activities accordingly. This information will help you in wildfire prevention and could prove valuable if a fire gets out of control.• Keep appropriate firefighting tools nearby and make sure they are in good condition.

• Keep a step-by-step checklist handy in case wildfire should occur. A checklist is essential during times when you may not be able to think clearly in the heat of the moment.

• Make sure that the civic number of your property, or some other means of identification, is prominently displayed at the end of your access road.

• Have your woodland management map or aerial photo readily available for firefighters should thy need it.

• Your woodland roads and bridges will be vital in firefighting efforts! Know their limits and whether they can support the weight of loaded fire trucks. The maximum weight capacity of each bridge should be clearly posted from both directions.

• Make sure there is unobstructed access to woodland ponds, which may be valuable as firefighting water sources.

Assurance through Wildfire Insurance

An important planning component that is often overlooked is making sure that you are adequately covered by fire insurance. Suppression costs of a major wildfire can easily escalate to hundreds of thousands of dollars. Owning an insurance policy that covers public liability and property damage can be of enormous benefit should a wildfire damage neighbouring property. Be sure to specify “fire damage” when discussing such a policy with your insurance agent. A minimum of $2 million in coverage is a good figure from which to begin.

If a woodland contractor is working on your property, you should have a signed written contract that describes the responsibilities and duties of each party. Many contractors have public liability and property damage insurance. Check the amount of coverage and whether fire damage is specified in the policy. Make sure the contract states that the contractor must have fire insurance and that the coverage is for a minimum of $2 million. This will help protect you in the event of a contractor-caused wildfire.

Planning for Wildfire Prevention: Other Considerations

Many of the steps that you can take to prevent wildfire are simple and easily accomplished. For example, working in the forest when the fire risk is extreme could be inviting disaster. Doing the same work earlier in the morning and later in the afternoon can prevent the worst from happening. This precaution should be extended to contractors who may be working on your property. Gauging the fire risk by checking the hazard index and being constantly aware of the conditions around you makes good sense and is a basic prelude to safely working on your woodland.

It is always a good policy to carry a mobile phone while in the woods. During fire season, a phone call will summon help if it is needed. Always make sure your phone is fully charged and never assume that firefighters can quickly find our location. Post the civic number of your property or your name at the road entrance, mark road intersections with flagging tape, and be prepared to give GPS coordinates if possible. For those working in remote locations, emergency GPS transmitters are available, which can provide an extra measure of security.

Lesson 2 - Woodland Fuels and Wildfire Behaviours

It is important to learn about and manage the amount of fuel that is present on your woodland. A fie is not sustainable without adequate fuel, and that is a good thing when you are a woodland owner!

If a wildfiie begins, it will act according to three factors: weather, topography, and fuel. Fuel is the only factor that you can control. This lesson will address the importance of good fuel management and wildfiie behaviour, in the context of your woodland.

The Essential Ingredients of Fire

Fire needs three ingredients to exist: fuel, oxygen, and a source of ignition (heat). If one ingredient is absent, fie is impossible. Both fie prevention and firefighting depend on removing at least one of these three factors.

Together, the three factors are called the fire triangle. While it may be impossible to control oxygen and heat at the outset of a fie, the availability of fuel can be managed, which is often the key to preventing the spread of fie.

Combine a warm summer day with dry leaves and a carelessly dropped match or cigarette butt, and all the ingredients for a fie are present.

|

|

|

|

Sources of Heat

Despite the presence of large amounts of fuel in most woodland, a source of heat is needed for the fuel to combust. Heat can arrive in the form of a still-burning cigarette butt, a blast of lightning, or a poorly kept campfire. While human activity is by far the most common source of heat, it should be the most easily managed. Often, however, human carelessness knows no bounds!

Lightning

Many people in Nova Scotia believe that most wildfires are started by lightning strikes during spring and summer. This is a common misconception. In Nova Scotia, lightning causes less than 2 per cent of wildfires. While lightning is an intense and powerful source of heat, most of the time it does not strike suitable fuels and the fierce energy is dissipated by the soil.

Lightning is caused by a discharge of static electricity that forms in the atmosphere. When positively charged particles (called ions) build to a critical mass, electricity is released as an outlet of lightning. It may or may not be accompanied by thunder.

|

|

It is common for lightning to seek the shortest route from its point of origin in the atmosphere to the earth. While not all lightning reaches the earth, those lightning bolts that do make a connection are often attracted to tall objects such as trees.

If lightning strikes a tree, the effects can be spectacular. Trees route much of lightning’s energy into the ground, with resulting split trunks, broken branches, and roots that may be blown out of the ground. People who have seen lightning strike a tree often describe the impact as a detonation.

When ground vegetation around a lightning-struck tree is dry, the sudden blast of heat can cause a fie. At the very least, much of the vegetation is killed by the burst of energy. If the organic layer of the soil is sufficiently dry, a fie may smoulder for days beneath the surface before finally becoming a wildfire.

In some instances, a tree that has been standing dead for years (called a snag) provides a good fuel source, and a fie may be ignited within the tree. These snags can smoulder for days. If given suitable dry, hot, breezy weather, they could spread to become a wildfire.

|

Such examples are rare in Nova Scotia. While many lightning strikes happen each year, few ignite fires that reach a significant size. Clearly, lightning strikes cannot be blamed for any appreciable number of fires—even within a decade or longer. Environment Canada monitors lightning strikes across the country, and while they can result in huge wildfires in western Canada, such fires are hardly noticeable in Nova Scotia.

Human Activity

Nearly all wildfires in Nova Scotia are caused by human activities. While large-scale burning for agriculture is mainly restricted to blueberry fields, other forms of burning are still fairly common in Nova Scotia.

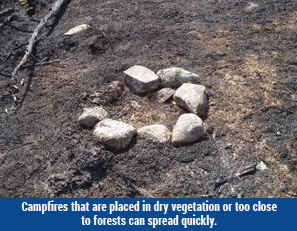

Burning trash is an illegal practice, yet some homeowners continue to do it. Although it is not illegal to burn waste wood outdoors in a controlled setting, these fies can escape into the forest, with drastic consequences to populated areas. Campfies, too, can flare up under the right conditions, get into forested areas, and spread rapidly.

|

|

Perhaps less common are fires that are started by mechanical equipment. Metal parts striking stone can cause sparking, while parts can overheat and induce combustion in dry vegetation. Heavy-duty mowers, if operated during extreme fie hazard conditions, can cause sparking and ignition of fires. For woodland owners who keep their access roads mowed as regular maintenance, this can be an important consideration. Mowing vegetation when it is damp can help prevent combustion.

Hot engine or exhaust parts can ignite dry leaves and grass. Simply parking or idling a vehicle over a dry pile of leaves or other vegetation has been known to cause fires. Combustible material can also accumulate in vehicle chassis, and it is always a good idea to keep your vehicle, including ATVs, clean of debris.

The hot engine of a chainsaw, too, can ignite dry vegetation. Keep fuel containers well away from these sites, and use caution when setting your saw down. During extreme fie weather, you may wish to reconsider working in the woods at all until conditions improve.

Other fie-causing human activity includes the crime of arson. Deliberately setting fires for the purpose of nuisance or vandalism can have serious consequences. Arson can have tragic and lasting results, including property damage and lost lives.

Whether accidental or deliberate, wildfires that are the result of human activities can be a significant threat to your woodland property. Making sure proper precautions are taken to prevent fires is everyone’s responsibility, and there are some actions that you can take to minimize the risk your woodland will be affected by wildfire.

How does a Wildfire Start?

In Home Study Module 7 (Woodlot Ecology: Your Living Woodlot), we learned that plants absorb sunlight (radiant energy), carbon dioxide, and water. Through a process called photosynthesis, these compounds are turned into sugars and oxygen. The sugars are used for plant growth and are stored as chemical energy.

When plant material burns, chemical energy is transformed into thermal energy, releasing heat, carbon dioxide, and water. Once fuels reach critical temperatures, gases within the plant material become volatile and will readily burn. Dry leaves, needles, and twigs are fine fuels that burn rapidly once ignition temperatures are reached.

As a fie feeds on these fine fuels, the temperature of the fie rises and the fie is able to consume larger fuels such as ground vegetation, branches, and small trees. If a breeze is present, more oxygen is available to the fie, further increasing its temperature and rate of spread. Under these conditions, a fie may soon grow out of control for one or two people and become a wildfire.

What Factors Influence Wildfire Behaviour?

Once a wildfire has started, fuel, weather, and topography combine to influence the behaviour of the fie. If large amounts of fuel are present across the landscape, the intensity of the wildfie will increase. Weather will affect the amount of moisture present in the fuel, influence the depth to which a fie will burn in the forest floor, and dictate the length of time embers within the ground will smoulder. If the topography of an area is hilly and fie is travelling uphill, its rate of spread will increase.

If enough fuel and oxygen are available, a fie will continue to burn and expand in size. As a fie burns, it preheats fuels that are in its path, accelerating the pace at which it can travel and consuming larger pieces of fuel. If it becomes large enough, a wildfire may even begin to form its own weather!

|

|

In most instances, wildfires are quite predictable in their behaviour, which is of great interest to fie managers. If a fie should start on your woodland, you would also want to know how it will act! Fire behaviour can be predicted by referring to the fie behaviour triangle, a useful tool that forest fie managers have used for decades. The triangle, shown below, depicts fuels, weather, and topography all working together to influence the ways in which fires behave.

|

|

|

|

It should always be remembered that fie will travel uphill faster than on flat terrain. As heat rises, the fuels above the fie will dry and ignite more quickly. If your woodland is located on a hillside, a wildfire starting at the bottom may travel much more quickly than a fie on level ground. This can be an important safety consideration.

Of all the factors that affect a fie’s behaviour, wind speed is the most important. Not only will wind decrease humidity, but a small flame can be quickly fanned into a large blaze if wind is present. A fie will also travel more rapidly as wind speed increases. If a fie is travelling uphill and a wind is pushing it upwards, the fie will travel even more quickly. Once a fie becomes very large and intense, it can create its own weather, to the point of influencing wind speeds and forming fie tornadoes.

|

|

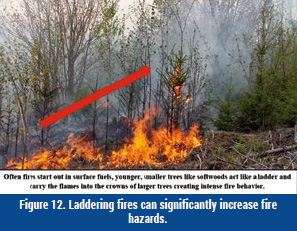

A wildfire at ground level, called a surface fie, can often be effectively controlled. If the fie jumps into the canopy of a forest, suppression efforts become much more difficult. Fies travel from the ground to the crowns of trees by a process called laddering. When forests are dry, laddering can happen rapidly and may be difficult o contain once it has begun. Ladder fuels include understory trees and shrubs that act as steps to convey fie upwards. Once a wildfire has reached tree crowns, it is potentially more dangerous since it will travel more quickly in the presence of wind and will be more difficult o control.

Weather and Climate

Nearly everyone has noticed that the patterns of weather and climate in Nova Scotia are changing. With warmer winters and summers and wetter, windier autumns, the frequency of extreme weather events appears to be increasing. It is important to note the difference between weather and climate in the context of Nova Scotia’s woodlands. Weather is a local atmospheric condition that affects relatively small areas of the landscape over a short period of time. Climate affects weather and is a larger, regional phenomenon that has a much broader time frame, often measured in decades or centuries. Over the long term, the results of climate change can be more significant than changes in weather.

Climate change can influence annual maximum and minimum precipitation and temperature. It can dictate the species of vegetation—including trees—that are growing on your woodland, as well as affecting long-term drought and flooding. Weather patterns follow climate, and both have direct impacts on fie weather and the risks of wildfie.

Scientists have developed ways of measuring the risks of potential wildfie based on data reflecting atmospheric conditions and of flammable substances on and beneath the surface of the ground. These measurements are compiled into a valuable tool called the Fire Weather Index system.

The Fire Weather Index System

The Fire Weather Index (FWI) system is a weather-specific ool for predicting potential fie conditions on any day in Canada. It is a compilation of six factors that together predict the potential intensity of a wildfie. Three factors are associated with the moisture content of forest fuels and three are related to fie behaviour. The FWI does not take into account the types of fuels that may be present or the topography of the landscape.

The six components of the Fire Weather Index are

- Fine Fuel Moisture Code: A rating of the moisture content of litter and other fin fuels, which can be used to predict ease of ignition and fuel flammability.

- Duff Moisture Code: A rating of the moisture content of the upper duff (organic) layers of the soil and medium-size coarse woody debris.

- Drought Code: A rating of the moisture content of the lower layers of organic soil that can be impacted by seasonal drought. This rating can be used to predict the probability of deep smouldering in the duff layer and in larger-size coarse woody debris.

- Initial Spread Index: A rating that takes into account the wind speed and fine fuel moisture code to gauge the rate at which a fie may spread.

- Buildup Index: A combination of Duff Moisture Code and Drought Code, the Buildup Index rates the total amount of fuel available for combustion.

- Fire Weather Index: A rating that combines Initial Spread Index and Buildup Index, the Fire Weather Index predicts fie intensity.

The Fire Weather Index is usually depicted on a map, with different colours representing areas of predicted fie intensity. Blue is associated with low intensity and red is associated with extreme fie intensity. Green, yellow, and orange represent moderate, high, and very high intensity ratings.

The Fire Weather Index System is used to produce Fire Weather Forecast Maps, which are posted online as 8-hour forecasts and 24-hour forecasts. The maps are updated each day during fie season (March to October).

Fire weather forecast indices are also available each day during fire season. They are calculated using five indicators that are collected from more than 30 sites across the province:

- temperature

- relative humidity

- wind direction

- wind speed

- rain quantity forecast for 24 hours

The maps and indices are available at http://novascotia.ca/natr/forestprotection/wildfie/forecasts.asp

Module 16 - Quiz Lesson 2

| Questions: | 10 |

| Attempts allowed: | Unlimited |

| Available: | Always |

| Pass rate: | 75 % |

| Backwards navigation: | Allowed |

Module 16: Wildfire and Your Woodland - Lesson 2 - Case Study 1

The smoke was hardly noticeable until noon. By that time, the last crushed cans had been collected and the straying plastic wraps gathered into a large bag. It was, for all intents and purposes, a cleaned-up campsite, with little to betray the intensity of the previous night’s party.

It had been quite a night. There had been music, in the form of two guitars and a set of spoons, which proved sufficient a the night progressed. There were the few sleeping bags—in the end just enough for the eight teenagers. Greatest of all had been the bonfire, and what a bonfire! The leaping flames had awakened a primitive kind of dance among the party-goers. Those who did not dance sat galvanized, staring into the writhing flames, their senses both dulled and sharpened by the orange firelight.

In the cool, gray May dawn they had woken, laughing, stumbling through the brown-topped grass to hunt the snack bags that had started to scatter with the morning breeze. “Be sure and get everything,” one shouted as they combed the area for litter. The fire, now a blackened mound in a rough stone circle, was forgotten as the two cars roared off.

Tuned to the patterns of the departing campers, blue jays visited the campsite that morning. They shrilly argued over bits of popcorn and a discarded egg sandwich before they too departed. A raven stared down from the top of a tall spruce tree. The breeze was freshening as the big bird caught the next gust and glided away downwind.

|

|

By noon the glowing orange coals, hidden deep in the black pile of ash, had begun to shed sparks. Like tiny seeds, the bright embers scattered just outside the stone circle. They found flammable fuel in the dry stalks of grass and fed slowly until the next gust of wind ignited one into a single small, hungry flame.

In less than 10 minutes, the fie had found new fuel and entered the surrounding softwood forest. The broken top of a balsam fir tee, felled by the last winter’s winds, lay directly in the path of the flames. Old fir cones, still attached to the branches, were covered in dried resin. In seconds, needles, cones, and twigs flared as the tree top was engulfed in a snapping, sparking blaze.

As the fie advanced further into the forest, it found new fuel. The thick moss beneath spruce trees began to smoulder and thick acrid smoke spiraled skyward. A chipmunk, alarmed at this intrusion, didn’t stop to scold as it vanished into a hole at the base of a tree. The low branches of the spruce trees, dry at this time of year, started to smoke.

Where the ground vegetation was thick, some moisture was still present, which slowed the progress of the fie. Damp maple leaves lifted off from the forest floor as the hot air launched them upwards. Some leaves glowed as the breeze pushed them into the forest.

The fie was gaining momentum as the flames, ladder-like, climbed the low shrubs and reached the lowest branches of the spruce trees. The first tee branches erupted in a sparking flash as the tinder-dry needles ignited. Surrounding trees soon caught as the fie crowned and became an inferno of heat. Pushed by the strong breeze, it leaped from tree to tree, engulfing everything in its path. The white smoke could be seen for kilometres as it raced toward a subdivision of dwellings.

The throbbing drone of a helicopter soon joined the roar of the fie. It circled as the crew assessed the speed, direction, and intensity of the fie. Firefighters o the ground deployed at the edge of the subdivision and emergency trucks sped past the startled and fearful homeowners who were being evacuated even as the smoke rolled thickly through their neighbourhood. Hundreds of metres of fie hoses were unrolled and snaked through the trees like giant spider webs, forming a front nearly a kilometre wide. Scores of firefighters race to confront the fie at a narrow woods road just inside the forest. It was there that they would attempt to stop it.

|

|

A larger helicopter with a water bucket joined the first aircraft, jettisoning its load at the leading edge of the fie. Clouds of steam rose as the water smothered some of the flames and the fie’s advance hesitated. The helicopter flew to a nearby lake to refill the bucket. White arcs of spray fanned out through the trees as thousands of litres of water poured through the fie hoses. When hot embers descended through the smoke and onto the roofs of houses, hoses were turned on the houses to keep them from igniting.

The helicopter was relentless in its continuous cycle of refilling and dumping water on the fie. A fuel truck had been positioned in a local ball field for th inevitable moment when fuel began to run low, and the helicopter was not long in returning to its circuit. By early evening, no large flames were visible from the air.

The work on the ground started in earnest as firefighters began the exhausting task of extinguishing hotspots with back tanks and shovels. The entire area of the fie, which had been nearly 20 hectares, would need to be thoroughly combed for signs of smouldering embers. It would be a long night.

|

|

As the helicopters clattered off and evening descended, people began to return to their homes. Most were shocked to see how closely the fie had come to destroying their houses and everything in them. Fire hoses lay everywhere. The hoses still trailed off into the forest, where they would be retrieved the next day.

The home that was closest to the fie received the most damage. It had been continually hosed as the embers from the fie descended on and around it. Thanks to the efficient work y fiefighters, th house had been saved. The family had been evacuated quickly, so quickly that they had no time to collect any belongings. A teenage daughter looked in vain for a blue earring she must have lost while they were scrambling to get to their car. Her father shook his head as he surveyed the damage to the back lawn where a tanker truck had been briefly stuck.

At dawn the next day, the firefighters wee still mopping up hotspots. The local church had provided sandwiches and drinks, and replacement crews were due to arrive shortly. The provincial fie chief had arrived by helicopter to determine the cause of the fie and the extent of the damage. “Set it down here,” he told the pilot.

As he got out of the aircraft, he knew that this site was where the fie had started. A crude ring of stones told the tale of the fie’s beginnings. Perhaps campers or hikers came through here yesterday, he thought. Partiers would probably have left some litter. He kicked at a stone, then bent over and picked up an object from the charred grass. He held it up and caught a gleam of colour from beneath the black soot. A blue earring. He put the evidence in a clear plastic bag and walked back to the helicopter.

Lesson 3 - Wildfire Prevention on your Woodland: Critical Steps

Decreasing the risk of wildfire should be a primary consideration for every woodland owner. Adopting a mindset in which you are responsible for the defence of your property is often the first step in constructing a strategy for reducing the risk of wildfire. By using a proactive approach, wildfire is preventable and—should a fire escape—damage to your property can be minimized. As we learned in Lesson 1, you can initiate wildfire prevention by removing potential fuel sources and making sure that fire has fewer opportunities to develop into a wildfire.

Reduce Your Fuel Load

There are many steps you can take to reduce the availability of fuels and make sure your property is protected from wildfire. If you have a camp, trailer, or other dwelling on your woodland, you should be even more cautious in your approach to fie prevention. Following is a checklist you can use to make sure you have taken the necessary steps to prevent wildfire:

|

|

Construct Woodland Ponds

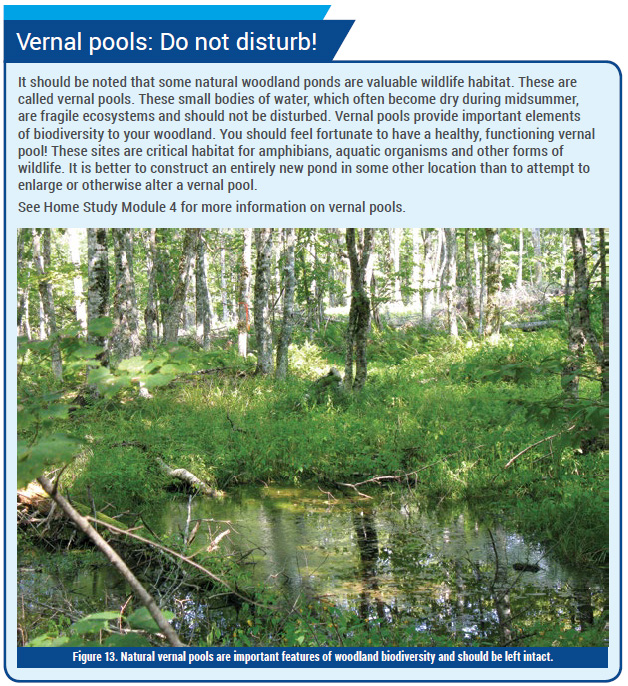

One of the most significant structures a woodland owner can construct to control fires is a fie pond in an accessible location. Fire ponds provide the peace of mind that year-round water is available if it is needed to suppress a local fie. If there is already a natural pond in an accessible location on your woodland, make sure that it is large enough to hold plenty of water year-round. Be sure it is not a vernal pool, since these small areas contribute immensely to the biodiversity of your woodland.

|

|

Woodland fie ponds are not difficult o construct. The best time to choose a location for a pond is when you are building a woodland road, since the excavated soil can be used in road construction. Small sites with year-round supplies of fresh water located next to a road are good choices for ponds.

You may be surprised how quickly a woodland fie pond assumes a character of its own. After construction, the margins of the pond soon teem with plants and insects, while amphibians begin to inhabit the shallows where there is abundant food.

Figure 14. A woodland pond can be a valuable source of water Like any body of water, a fie pond can be potentially hazardous to forest workers and the public. It is your responsibility as the landowner to make sure that your pond is safe for everyone. The pond should be clearly marked with signage to indicate that deep water is present, particularly if it is adjacent to an access road.

|

|

Ponds as Habitat

Any small bodies of water in woodlands are natural habitats for wildlife, including wetland plants. Constructed ponds may replicate vernal pools, which are some of the most valuable wildlife habitat in woodland areas. Here, freshwater aquatic organisms live in close proximity to terrestrial animals and birds. Salamanders, newts, frogs, and other amphibians are important inhabitants of pools and ponds. They feed on small invertebrates and in turn provide food for animals and birds further up the woodland food chain. Raccoons, mink, red fox, and other mammals may stop by to check on the resources your pond has offered them. If you are really fortunate, your pond may support a small colony of fish lie sticklebacks, mudpuppies, or brook trout, adding another dimension to the health and wealth of your woodland.

For further details on conserving and enhancing woodland habitat, see Home Study Module 4 (Woodlots and Wildlife).

|

|

By reducing the fuel load and making sure that an ample supply of water is available if it is needed, you have taken the critical first steps in peventing wildfie on your woodland. By constructing or maintaining a fie pond, you will have also contributed to the wildlife habitat on your property—and added a significant component o the biodiversity of your woodland!

Lesson 4 - Steps to Prevent the Rapid Spread of Wildfire

Once a wildfie has begun, it is too late to plan prevention! Planning must take place before a fie has even started. It is very important to recognize that your woodland is the fuel upon which a wildfire feeds. Do not provide a fie with an abundance of fuel! This section will address methods by which you can reduce the presence of woodland fuels.

|

|

Create Woodland Diversity

One of the ways you can plan to slow the rate of potential wildfire is by increasing the diversity of your woodland. Diversity is an important consideration when determining the rate at which a wildfie will spread. A mixture of softwood and hardwood contained in patchy and irregular stands, and with few ladder fuels, will help prevent wildfire. On the other hand, the presence of large quantities of dead softwood trees, brush, and debris will contribute to an increased risk of wildfire.

Diverse woodlands are healthy woodlands. Not only do mixtures of tree and shrub species encourage wildlife diversity, they also discourage outbreaks of forest insects and diseases. Large areas of single-species trees of the same age can be more susceptible to devastating natural events such as wind, insects, and wildfire.

Riparian areas that are found along watercourses are often some of the healthiest forest ecosystems because they support a diverse abundance of herb, shrub, and tree species. Many wildlife species also frequent these areas because of the diversity of plant and aquatic life. Large mammals use them as travel corridors. Riparian areas provide valuable natural fie breaks should a wildfie occur.

|

|

Exercise Caution Around Woodland Thinnings

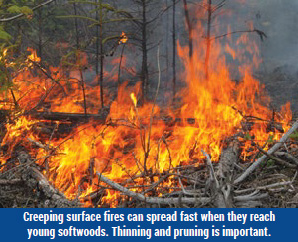

If you have an area of pre-commercial or commercial thinning on your woodland, extra care should be taken to prevent fie from starting or gaining a foothold on these sites. With large quantities of dried brush present in a thinning, the likelihood exists that fires could easily ignite the brush, with the added threat that a surface fie may ladder into the crowns of the thinned trees.

Where a thinning is close to a frequently travelled road, it is a good idea to clear the brush back from the ditches and margins of the road. This will help prevent carelessly thrown butts and other sources of ignition from starting a fie in your thinning.

Respect the Hazards of Spring Season

Nearly everyone recognizes the danger present in the dry woodlands of spring. Just before hardwood buds burst and ground vegetation blossoms, wildfire hazard is at its peak. Hardwood leaves, dried by the warming sun, are crispy underfoot. Softwood twigs break in startling snaps. The heat of a sunny spring day warms the air, carrying moisture skywards. At these times, the forest is ripe with potential for wildfire.

Softwoods are at their driest in early spring. Although hardwood trees have not yet leafed out, softwood needles, twigs, and branches are highly flammable if they are dry. Needles and twigs are the fine fuels that burst i ignition and generate heat, while medium-size and heavy branches sustain hot fies by giving life to flames and embers.

When the wildfie hazard is at its peak in late spring, it may be a good idea to avoid working in the woods. At this time, mere sparks can suddenly grow into flame that may be difficult o contain. Plan your woodland activities accordingly—don’t run equipment during the hottest part of the day, and refrain from creating any kind of spark or ignition that may start a wildfie.

Remember: Your woodland is the fuel on which wildfire feeds.

|

|

Module 16 - Quiz Lesson 4

| Questions: | 10 |

| Attempts allowed: | Unlimited |

| Available: | Always |

| Pass rate: | 75 % |

| Backwards navigation: | Allowed |

Lesson 5 - First Strike: Tools and Equipment for Wildfire Fighting

We’ve looked at the importance of reducing the potential wildfire fuel that may be present on your woodland and access roads. Despite your best efforts, wildfire can still be a threat. While prevention measures go a long ways toward reducing the risk of wildfire, events can take place that are beyond your control. If a fie should start on your woodland, it can often be extinguished if the proper tools are at hand, and in good condition. No one wants to be facing a small blaze with a broken shovel or non-functional back tank!

The Importance of Proper Equipment

If you are carrying out work on your woodland by yourself during fie season, you should have on hand a shovel and a filled back tank, at a minimum. Mechanical equipment that may be on-site, such as a farm tractor, should have an approved and inspected fie extinguisher on board and easily accessible.

Heavy equipment working in the forest must carry fie suppression gear, and most modern harvesters and forwarders are outfitted wit onboard fie extinguishers and spark arresters. Older equipment, particularly skidders and forwarders, may not carry such devices and it is up to the owner or operator to make sure the proper fie equipment is present.

SHOVEL

A shovel can be the most useful fire suppressant tool you can have on hand. Small surface or grass fires can be beaten down with a shovel. You can also create a small fire break in the path of a fire, and soil can be quickly shoveled on a fire to smother it. A heavy-duty shovel can be used to break up large smouldering embers into smaller chunks, which can then be covered in soil. Make sure that your shovel is in good condition, and inspect the handle regularly for cracks and other damage that is often overlooked.

|

|

It is important to make sure that mineral soil is used to extinguish embers, rather than the top organic layers of the soil (commonly called duff), which may contain combustible material. You don’t wish to be adding fuel to the flame!

Back Tank

Although it will cost a few hundred dollars to purchase, a back tank can be essential in helping to control the spread of a small fie. Make sure that during fie season your back tank is filled at all times, voiding the awkward situation of having an empty tank when you may need it most!

The water from a back tank helps extinguish a fie by both smothering and cooling the flames and embers. Blasts of water from a back tank pump can effectively penetrate smouldering wood and duff. Adjustable caps on the nozzle can direct either a single jet or a shower of water. The shower often works well for drenching areas in advance of a fire.

|

|

In areas where water is not readily available for refilling our back tank, a large steel barrel or plastic tank can be used for storing water during fie season. Make sure the container is large enough to immerse the entire back tank for filling.

A back tank and shovel can be a very effective combination in controlling small woodland fies. Make sure these tools are available to anyone who is using your woodland during fie season and that they know their storage location.

Other Firefighting Tools

Although response times and effective firefighting techniques have improved over the past three decades, many tools remain much the same. Chainsaws are still used to clear fie breaks in the forest to prevent the rapid advance and crowning of wildfires. They can also be used to cut trails for the movement of firefighters and equipment.

Portable pumps, which run on gasoline engines, are used to draw water through hoses from streams, rivers, ponds, and holding tanks. The ability of pumps to quickly move water uphill makes them particularly valuable. Such pumps can cost thousands of dollars, depending on their size and complexity, and their price prevents most woodland owners and contractors from acquiring them.

Axes and grub hoes are useful in cleanup efforts once wildfies have been controlled. They can be used to cut through roots and debris to reach embers, and in scalping duff layers from the soil surface.

|

|

Module 16 - Quiz Lesson 5

| Questions: | 10 |

| Attempts allowed: | Unlimited |

| Available: | Always |

| Pass rate: | 75 % |

| Backwards navigation: | Allowed |

Lesson 6 - If a Fire Gets Out of Control

If a Fire Gets Out of Control

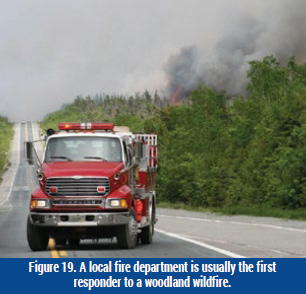

Once a fie grows to a size that is not controllable by shovels and back tanks, assistance from a fie department is absolutely necessary. You should waste no time in calling in the location of a fie and be prepared to give straightforward, easy-to-follow directions.

If a fie department can get tanker trucks close enough to the fie, they will run hose directly from the trucks. If a fie is in a location impassable to heavy trucks, portable pumps may be used to pump water directly from watercourses or ponds. This procedure can be a huge tactical effort on the part of firefighters, and several hundred metres of hose can often be required to access a remote woodland fire.

|

|

A fire department will call for additional support if a fire is in a woodland area. This will include NSDNR personnel and equipment, more pumps and hoses, and ultimately a helicopter equipped with a bucket for dropping water. Air dropping water and retardant may be the only way of controlling a fire that has climbed into the crowns of softwood trees.

While large fires are thankfully rare in Nova Scotia, there have been some huge wildfies in the past that have required an extraordinary quantity of resources to control them. One example is the Trafalgar Fire of 1976, which burned 130 km2, requiring the use of hundreds of people and bulldozers to create firebreaks on the landscape. In June 2008, the Porter’s Lake Fire—started by a campfire—burned 1,900 hectares of woodland, destroyed two homes, and necessitated the evacuation of 5,000 people from their homes. Large amounts of brush and woody debris created by Hurricane Juan in 2003 provided abundant fuel for this fie. Once fires reach the sizes in these two examples, suppression efforts and associated costs can be astronomical.

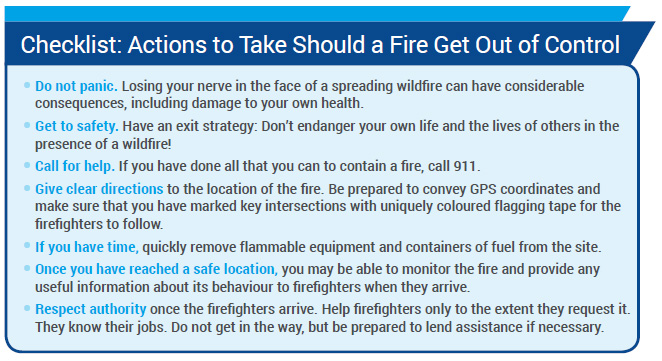

It’s important to have a checklist handy should even a small fie get out of control. It is not easy to remain clearheaded when a potential wildfire is developing on your woodland. The checklist should be kept in an easy-to-reach location, such as a firs aid kit. To make it even easier to find, th checklist should be printed on brightly coloured laminated or waterproof paper.

What actions should be on your checklist?

|

|

|

|

Because of effective modern fire fighting equipment and methods, large fires in Nova Scotia are rare. The potential for one, however, is present each fie season. Ironically, good prevention practices have resulted in an unprecedented buildup of fuels in Nova Scotia’s forests. A large, dangerous wildfire may be only a spark away! This makes it even more important for woodland owners to be extremely cautious during fie season, and increasing the odds that any wildfire—small or large—is prevented. Remember: Control fuels on your woodland and have the necessary tools available should you need them quickly.

Lesson 7 - Defending Your Home from Wildfire

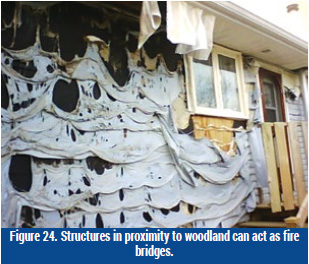

More people than ever are living near woodland. As urban centres become decentralized and larger, more expensive dwellings are built in rural areas, people are embracing rural life. Here, however, human activity and forest dynamics collide.

Agriculture and industrial development is commonly adjacent to the forest. Many woodland owners live close to their managed woodland and may have a camp on their property. Because fires can start in structures and spread to woodland, or start in the forest and engulf buildings, you as a woodland owner should understand how to prevent and control wildfires.

|

|

Unfortunately, many people who live in rural areas are not aware of the social, environmental, and economic consequences of woodland fires. Some may not even be convinced they have responsibilities toward fie and that this burden should rest with fie departments, the Department of Natural Resources, and other agencies.

Both woodland owners and homeowners near woodland should recognize that, because of decades of effective fie suppression, fuels have accumulated in woodland areas. In the same way that reducing fuel loading in woodland can reduce the risk of wildfire, managing the availability of fuels in and around structures can also significantly lessen the chances of devastating fires.

|

|

On a larger scale, many Canadian communities have partnered with businesses and government to develop formal programs to reduce the risk of damage from wildfires.

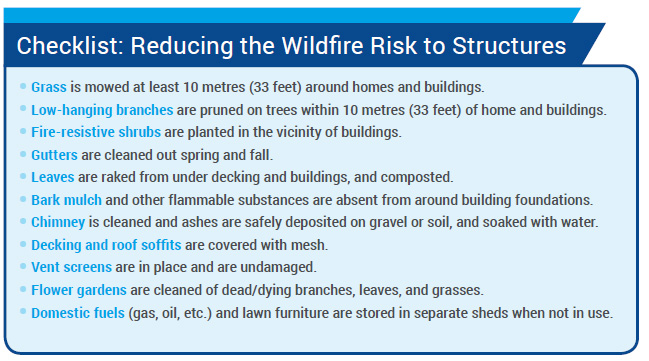

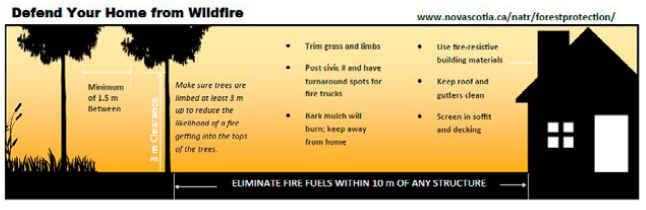

As a homeowner who may live in a rural area, you can decrease the susceptibility of damage to your home and other structures from wildfire. Following is a checklist that you can use to be FireSmart in defending your home.

|

|

Some homeowners feel that maintaining fie-defensible areas around dwellings results in unattractive premises. This is not true. It is a fact that the landscape around your home and structures can actually be enhanced by planting fie-resistive shrubs and trees. Many of these species are visually appealing and have the added benefit o being drought-resistant. It is important to choose low-growing shrubs, which prevent the laddering of fie into tree crowns or structures. Shrubs with high water-content sap, rather than flammable resins, are also preferable. Prune and maintain your shrubs to reduce any buildup of dead wood and other flammable materials.

|

|

Be sure to talk with your neighbours about the risks of wildfire and the steps they can take to avoid catastrophe should a wildfire approach their dwellings. For more detailed information about ways to reduce the risk of wildfire damage around your home and to become FireSmart, visit www.fiesmartcanada.ca.

Lesson 8 - Keeping Wildfire in Perspective

Wildfires can result in serious personal and economic loss. When subdivisions and rural dwellings are affected, it can be difficult to even quantify loss in financial terms.

In a best-case scenario, the costs of woodland fires may be

- suppression costs

- loss of adjacent woodland resources, including timber

- inconvenience

A worst-case scenario of the costs of wildfire may be

- suppression costs

- loss of life and property

- costs of evacuating a community

- social, environmental, and economic rehabilitation

It is clear that every wildfire poses the risk of substantial loss to people and the environment. There are times, however, when fires can be beneficial if carefully managed and controlled. After all, fie is a natural disturbance event that has changed the structure and composition of woodland for thousands of years.

The Benefits of Woodland Fire

Not all woodland fires are considered destructive. Some actually benefit forest ecosystems.

Because fire happens naturally in woodland, it is responsible for recycling carbon-based fuels, such as vegetation, and reducing it to levels that are less fie prone. Fire also results in different plant species colonizing an area soon after the fie, which may increase the site’s capacity for wildlife habitat. Fire can be used by managers to reset the vegetation types in some areas of woodland and, in some instances, may reflect a more natural process of succession than modern forest harvesting (see Home Study Module 2, Woodland Harvesting).

Fire can alter forest ecosystems in unique ways, and some tree species such as jack pine (Pinus banksiana Lamb.) require elevated temperatures to open their seed cones. Pin cherry (Prunus pennsylvanica L.f.) seeds are particularly tough and resistant to temperature extremes, and can remain viable in the soil for decades. This species flourishes vigorously after fie, earning it the nickname fie cherry.

In addition to shaping the succession of forest ecosystems by promoting new plant growth, periodic fies can clear woody fuels in areas before they become too heavily loaded and become a fie hazard. Creating fie buffers around structures by harvesting and removing woody fuels can achieve the same result.

|

|

Light prescription fires may be deliberately used as management tools. For example, in the eastern US, light understory fires are used to control invasive plant species like glossy buckthorn (Rhamnus frangula L.). In Nova Scotia, blueberry farmers regularly burn their fields o rid the sites of older blueberry plants and regenerate new ones.

In Nova Scotia, prescribed burning has limited application. Intentional burning is sometimes carried out in areas such as national parks where forest harvesting may not be available. Here, the total absence of fie disturbance for up to a century has inhibited natural succession of forest ecosystems. Small controlled burns are used in an effort to re-establish some plant species, forest succession dynamics, and wildlife habitat. Archaeological sites are sometimes burned to reduce damage to artifacts caused by roots.

|

|

Brush Piles: To Burn or Not to Burn

Property owners often wish to remove branches and other coarse woody debris from a site to make the area more aesthetically pleasing. But there is a good reason for leaving brush scattered over a site where trees and shrubs have been cut. Most importantly, branches, leaves, and needles are organic materials that contain nutrients valuable for plant growth. Removing this material from the site by burning it may significantly decease the nutrient content of the soil. Mulching, grinding or mowing brush with a bush hog are possible alternatives if you have access to equipment.

Burning brush piles on some soils can also alter the upper soil structure and kill many of the invertebrates and microorganisms, including beneficial mcorrhizae (root fungi), that contribute to the maintenance of healthy soils. If you must burn, smaller brush piles generate less heat and may be better for keeping your soils healthy. As always, plan your burning in a way that will reduce the risk of wildfire.

|

|

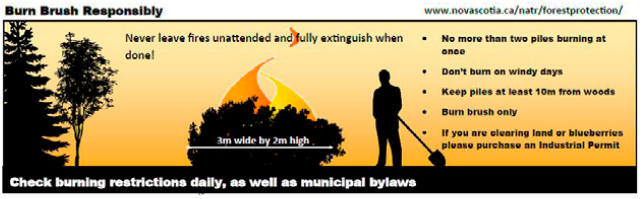

Brush piles should be no more than two metres high and three metres wide. The piles should be at least 10 metres from each other and at least 10 metres from the edge of the woods. It’s a good idea to burn no more than two piles at once. For large piles, industrial permits can be obtained from your local NSDNR office.

But do you really need to burn that brush pile? Where brush piles have been created, they often provide good wildlife habitat. Ground-dwelling birds such as ovenbirds, winter wrens, and white-throated sparrows use piles that are a year or two old. Mammals like meadow voles, snowshoe hare, chipmunks, and least weasels use brush piles for shelter and for hunting for food. Reptiles and amphibians congregate in brush piles where moisture is usually high and temperatures are cool. These include salamanders, newts, and garter snakes. In as little as two or three years, if left intact (and perhaps even built larger with fresh material), a brush pile is usually teeming with life.

Should you burn that brush pile? This question is an important one for property owners!

|

|

Burning Grass: A Spring Ritual

It is one of the scents of spring: the rich, pungent aroma of burning grass. Everyone seems to do it, from rural homeowners who burn their ditches and lawn edges to blueberry growers who burn grass and old growth from their plants to make way for new shoots.

There is something compelling about burning grass: torching the old to make way for the new, the green grass looking even greener against the blackened sod. But the fact is, aside from the visual appeal, burning grass can actually do more harm than good. First, the grass and other vegetation that could be returning to the soil as nutrients is instead literally going up in smoke.

Second, weeds that have seeded out the previous year are not likely to be destroyed by burning. They may come back thicker than ever, while grass coverage is actually reduced by up to half from burning. Weeds that have a knack for aggressively colonizing new sites will likely occupy areas left bare by burning.

|

|

Finally, you may be damaging wildlife habitat and the nests of birds, particularly when burning fields. Voles and mice rely on long grass and shrubs for shelter; burning the grass may displace them to less desirable locations (your house, for example). Raptors such as Northern harriers nest on the ground in open field and marshes, and landowners may not be aware that nests (and eggs or young) are even present. Burning a field can easily destroy a nest and its contents.

There are other risks associated with spring burning. If a fie gets out of control and escapes into woodland or adjacent properties, your costs of burning could rapidly escalate. Even with snow still present, spring burning of grass does not guarantee the fie will not spread. A light breeze can carry grass fies quickly and for long distances, even over —and under—patches of snow.

|

|

Following Regulations: Burning Restrictions

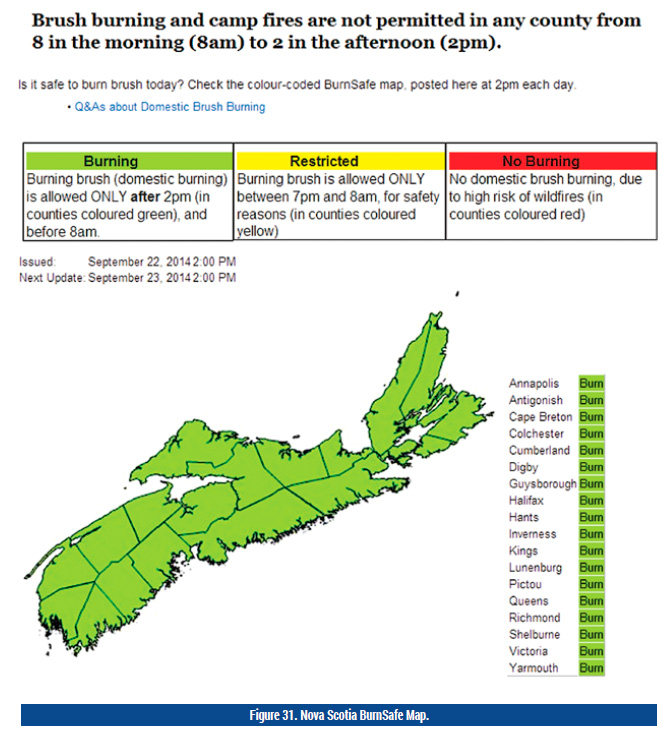

Domestic burning permits are no longer needed in Nova Scotia. Permits have been replaced by an online BurnSafe map, which must be consulted prior to burning. You can find this map at www.novascotia.ca/burnsafe.

To check whether there are any current burning restrictions in your areas, go to the NSDNR website. Even when the Fire Weather Index is low, there may be restrictions on brush burning and campfires.

Green, yellow, and red colour codes are used to indicate the levels of burning restrictions.

- Green: Burning brush (domestic burning) is allowed only between 2 pm and 8 am.

- Yellow: Burning brush is allowed only between 7 pm and 8 am.

- Red: No domestic brush burning due to high risk of wildfires.

It is important to note that there is no domestic brush burning between 8 am and 2 pm at any time during wildfie-risk season (March 15–October 15).

If you are clearing land for agriculture or development, industrial permits are required for brush piles larger than two metres high and three metres wide or for blueberry field larger than two hectares. These permits are available, for a fee, at your local NSDNR office. Its likely that a forest technician will visit the site prior to issuing a permit.The BurnSafe map must be referred to before beginning any brush burning in woodland or within 330 metres (1,000 feet) of woodland during wildfire-risk season (March 15–October 15).

|

|

Conclusion

Nearly everyone agrees that fires have both drawbacks and benefits.As a tool for clearing brush, for resetting forest ecosystems with a natural disturbance event, and for acting as a focus for social interaction, fie has long captured our imagination and respect. We cook with it, heat with it, and harness its power in many ways. The ecology of fie has long been the central character in human survival and progress.

When fie slips its leash and rages out of control, the human tendency is to step back (or run) and respect its appetite for destruction. As woodland owners, our properties contain the fuels that can transform a campfire into a firestorm.

Through prudent woodland management techniques and fie prevention efforts, we can stop wildfires before they begin. This module has outlined the steps that we can take to prevent and control woodland fires before they become wildfires. It is now our responsibility to step up and lay the vital foundations for wildfire-free woodland.

Module 16 - Quiz Lesson 4

| Questions: | 10 |

| Attempts allowed: | Unlimited |

| Available: | Always |

| Pass rate: | 75 % |

| Backwards navigation: | Allowed |

Lesson 8 - Case Study 2

Harold had felt pleased with himself. He had repaired the roof on his camp yesterday, just above where the squirrels had been making their way in and playing havoc with the plastic food containers in his cupboard. Some metal flashing had solved the squirrel problem, he hoped, and a half-dozen new shingles had sealed the deal. Now he hoped there would be no more leaks and even fewer squirrels in his small hunting camp.

Spring cleaning was a necessary chore. Harold didn’t use the camp much during the winter, except when some friends showed up on their snowmobiles and asked to use the camp for an overnight trip. He was happy to share, despite the squirrel problem.

His day had started by clearing some of the brush around the camp with his chainsaw—mostly small fir tees that had begun to encroach on the walls. He had worked at clearing brush all morning and the large pile of brush showed something for his efforts. Harold marvelled that there were still patches of snow in some places—it had been a fairly open winter and spring had seemed to come early.

Before setting out for his camp, Harold had checked with the local Department of Natural Resources office for a burnin permit. When he was told he didn’t need one, he wondered why, since he could always remember needing a permit once April arrived. The forest technician on duty had showed him a computer screen with the new BurnSafe map on it. Most of the province was coloured yellow, meaning Harold could burn after 7 pm and before 8 am at his camp property in Hants County. That was fine with him, since he was spending the weekend at the camp and this was only Thursday. Thanking the forest technician and promising her that he would recheck the map each day, Harold went on his way.

By Saturday Harold had cleared and piled the brush, and was looking forward to a quiet, restful Sunday. Both Friday and Saturday had been warm, windy days. He figued that things would soon start to green up in the woods.

He had a supper of fishcakes and beans before heading out to check the brush pile. Lots of brush to burn, he chuckled as he crumpled a newspaper and sparked his lighter. The paper caught the flame and crinkled as it burned. White smoke curled through the forest canopy as the flame flared and—just as promptly—died.

Well, thought Harold, he didn’t have much other paper apart from the essential kind in his little outhouse. He went over and picked up his fuel can, which was still half full of chainsaw gas. Liberally sprinkling the brush pile with gas, Harold once again flicked his lighter. Wow—that was better! With a roar, the pile erupted into flame, the fir needle snapping and sparking as they caught.

It took Harold less than two minutes to realize that he had made a mistake. The brush pile was quickly beginning to burn out of control. The dry carpet of leaves on the forest floor began burning in all directions and the flame soon reached other vegetation. Overhead, the shaft of rising heat and smoke created a current of wind that swirled among the softwood branches.

Harold wasn’t unprepared. He had a shovel handy and began swatting the escaping ring of fie, beating the leaves and shrubs that were now burning merrily. As soon as he had one side under control, another side would flare up, threatening to reach the surrounding softwood trees, which Harold had thinned just two years ago.

The brush pile was nearly consumed now, but there were other things to think about. A small fir tee caught fie, and another, sputtering and popping as the fie ate the dry needles. On the other side of the expanding circle of flame, the fie crept slowly toward the camp. Harold pounded the shovel furiously about him, realizing that the fie was getting well beyond his control.

Remembering something he had read in a booklet on forest fies, he started digging like a madman, prising the dark earth from the ground. He threw the soil on the fie, and one finger of flame disappeared. Harold continued, the sweat pouring down his face, his heart hammering, throwing soil as quickly as he could upon any flame he could see on the leading edge of the fie. Sweet mercy—he was gaining ground!

For the next 20 minutes, Harold alternated between swatting flames and smothering them with soil. Once or twice a smouldering clump of leaves would flare up and threaten to spread, but he reached them in time. Anywhere he could see smoke he threw soil, extinguishing the embers before they became flame.

Exhausted beyond measure, Harold leaned on his shovel and looked around. Blackened leaves were practically beneath his camp walls. On the other side the flames had stopped mere metres from his thinning; with the dry cut underbrush, the fie would have raced through the thinning. From there it was only a short distance to his neighbour’s property and hunting trailer; beyond that, a hundred acres of softwood and then a dozen houses. Good grief. So close to disaster, he thought.

To make sure there were no orphan embers, Harold walked through the brush and trees around his camp in expanding circles. He saw where one flying burning leaf had landed and now lay slowly smoking near an old stump. Harold put two shovelfuls of soil on it, just to be sure.

He realized now that over the past two days, the Fire Weather Index had risen beyond the yellow zone and into the red zone, on the map the forest technician had shown him. Harold knew he should have paid more attention to the clues around him, particularly to the warm breezy weather. He knew he should have checked the BurnSafe map again, before he ever lit the fire.

Harold was grateful he had had a shovel handy, but he knew he should have had more fie control tools at hand. A back tank ideally, a bucket of water or two at the very least. But the gear would not have been necessary if he had gauged the situation more closely. Much of what he should have done was only common sense, Harold concluded.

A rumble in the distance made him glance skyward: rain tonight. I could sure use that, he thought.

Module 16 - Glossary

Aspect -- The direction a slope is facing; its exposure in relation to the sun (e.g., north, east, south, west).

Back tank -- A portable water container equipped with a hand pump and backpack straps carried on the back of firefighters.

Burning Period -- That part of each 24-hour day when fires are generally the most active. Usually this is from mid-morning to sundown.

Combustion -- A chemical process in which heat is produced. In the case of wildfires, living and dead fuels are converted to mainly carbon dioxide and water vapour, and heat energy is released very rapidly.

Crown fire -- A fie that advances through the crown fuel layer of a forest, usually in conjunction with a surface fie. See surface fire.

Duff -- The layer of partially and fully decomposed organic matter lying below the litter and immediately above the mineral soil.

Fine fuels -- Fuels that ignite readily and are consumed rapidly by fie (e.g., leaves, needles, twigs, grass).

Fire Behaviour -- The manner in which fuel ignites, flame develops, and fie spreads.

Fire Behaviour Triangle -- A diagram in which the three sides of a triangle represent the three interacting components of fie weather, fuels, and topography.

Fire ecology -- The study of the relationships between fie, the physical environment, and living organisms.

Fire management -- The activities concerned with the protection of people, property, and forest areas from wildfire. Successful fie management depends on effective fie prevention, detection and suppression, and consideration of fie ecology relationships.

Fire prevention -- Activities directed at reducing fie occurrence; includes public education, law enforcement, personal contact, and reduction of fie hazards and risks.

Fire pump -- An engine-driven pump, usually gasoline powered, specifically designed for use in fire suppression.

Fire season -- The period(s) of the year during which fires are likely to start, spread, and damage property. See peak burn.

Fire triangle -- A diagram in which the three sides of a triangle represent the three factors necessary for combustion and flame production: oxygen, heat, and fuel. When any one of these factors is removed, flame production is not possible or ceases.

Fire Weather Index system -- A system of rating fie danger, consisting of six components: Fine Fuel Moisture Code, Duff Moisture Code, Drought Code, Initial Spread Index, Buildup Index, and Fire Weather Index.

Flammability -- The relative ease with which a substance ignites and sustains combustion.

Fuel moisture content -- The amount of water present in fuel, generally expressed as a percentage of the substance’s weight when thoroughly dried.

Green up -- The time during the first half of the season during which hardwood trees and understory vegetation have completed their flushing of new growth. This typically takes place in late spring/early summer.

Hot spot -- A small area of smouldering combustion that may be exhibiting smoke.

Ignition -- The beginning of flame production or smouldering as a fie starts.

Ladder fuels -- Fuels that provide vertical continuity and contribute to the development of crown fires. They can include tall shrubs, small trees, flakes of bark, and tree lichens.

Litter -- The uppermost part of the forest floor consisting of fresh or decomposed organic materials. A component of the duff layer.

Mineral soil -- That portion of the soil layers immediately below the litter and duff. Contains very little combustible material.

Peak burn -- The time of day when fie behaviour is at its most destructive, usually between 10 am and 5 pm during fire season.

Prescribed burning -- The knowledgeable application of fie to a specific land area to accomplish forest management or other objectives.

Pulaski -- A combination chopping and trenching tool, which combines a single-bitted axe blade with a narrow trenching blade fitted to a straight handle. Useful for grubbing or trenching in duff and root mats.

Slash -- Debris left as a result of vegetation being altered by forestry practices and other land use activities. Includes material such as logs, chips, treetops, and branches and uprooted stumps.

Spot fire -- A fie ignited by airborne embers that are carried outside the main fie perimeter. This is usually a small fie that requires little time or effort to extinguish.

Surface fire -- A wildfire that has limited vertical influence and is constrained to the herbs, shrubs, and organic layer on or near the forest floor.

Surface fuels -- All combustible materials lying above the duff layer of the soil. They can include litter, ground vegetation, shrubs, tree seedlings, stumps, and coarse woody debris.

Wildfire -- An unplanned or unwanted natural or human-caused fie.

Module 16 - Additional Woodland Resources and Contacts

Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources novascotia.ca/natr/

FOREST PROFESSIONALS

Registered Professional Foresters Association of Nova Scotia

www.rpfans.ca

Nova Scotia Forest Technicians Association

www.nsfta.ca

WOODLAND OWNER ORGANIZATIONS

Federation of Nova Scotia Woodland Owners

www.fnswo.ca

Nova Scotia Landowners and Forest Fibre Producers Association

www.nslffpa.org

Nova Scotia Woodlot Owners and Operators Association

www.nswooa.ca

Harvesting and Silviculture Contractors

Nova Forest Alliance

www.novaforestalliance.com

SILVICULTURE ASSISTANCE

Association for Sustainable Forestry

www.asforestry.com

WOODLOT ROAD ASSISTANCE

Forest Products Association of Nova Scotia

www.fpans.ca