Lesson 8 - Keeping Wildfire in Perspective

Wildfires can result in serious personal and economic loss. When subdivisions and rural dwellings are affected, it can be difficult to even quantify loss in financial terms.

In a best-case scenario, the costs of woodland fires may be

- suppression costs

- loss of adjacent woodland resources, including timber

- inconvenience

A worst-case scenario of the costs of wildfire may be

- suppression costs

- loss of life and property

- costs of evacuating a community

- social, environmental, and economic rehabilitation

It is clear that every wildfire poses the risk of substantial loss to people and the environment. There are times, however, when fires can be beneficial if carefully managed and controlled. After all, fie is a natural disturbance event that has changed the structure and composition of woodland for thousands of years.

The Benefits of Woodland Fire

Not all woodland fires are considered destructive. Some actually benefit forest ecosystems.

Because fire happens naturally in woodland, it is responsible for recycling carbon-based fuels, such as vegetation, and reducing it to levels that are less fie prone. Fire also results in different plant species colonizing an area soon after the fie, which may increase the site’s capacity for wildlife habitat. Fire can be used by managers to reset the vegetation types in some areas of woodland and, in some instances, may reflect a more natural process of succession than modern forest harvesting (see Home Study Module 2, Woodland Harvesting).

Fire can alter forest ecosystems in unique ways, and some tree species such as jack pine (Pinus banksiana Lamb.) require elevated temperatures to open their seed cones. Pin cherry (Prunus pennsylvanica L.f.) seeds are particularly tough and resistant to temperature extremes, and can remain viable in the soil for decades. This species flourishes vigorously after fie, earning it the nickname fie cherry.

In addition to shaping the succession of forest ecosystems by promoting new plant growth, periodic fies can clear woody fuels in areas before they become too heavily loaded and become a fie hazard. Creating fie buffers around structures by harvesting and removing woody fuels can achieve the same result.

|

|

Light prescription fires may be deliberately used as management tools. For example, in the eastern US, light understory fires are used to control invasive plant species like glossy buckthorn (Rhamnus frangula L.). In Nova Scotia, blueberry farmers regularly burn their fields o rid the sites of older blueberry plants and regenerate new ones.

In Nova Scotia, prescribed burning has limited application. Intentional burning is sometimes carried out in areas such as national parks where forest harvesting may not be available. Here, the total absence of fie disturbance for up to a century has inhibited natural succession of forest ecosystems. Small controlled burns are used in an effort to re-establish some plant species, forest succession dynamics, and wildlife habitat. Archaeological sites are sometimes burned to reduce damage to artifacts caused by roots.

|

|

Brush Piles: To Burn or Not to Burn

Property owners often wish to remove branches and other coarse woody debris from a site to make the area more aesthetically pleasing. But there is a good reason for leaving brush scattered over a site where trees and shrubs have been cut. Most importantly, branches, leaves, and needles are organic materials that contain nutrients valuable for plant growth. Removing this material from the site by burning it may significantly decease the nutrient content of the soil. Mulching, grinding or mowing brush with a bush hog are possible alternatives if you have access to equipment.

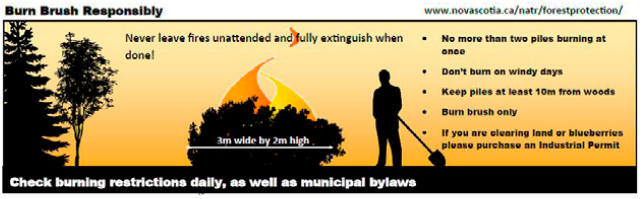

Burning brush piles on some soils can also alter the upper soil structure and kill many of the invertebrates and microorganisms, including beneficial mcorrhizae (root fungi), that contribute to the maintenance of healthy soils. If you must burn, smaller brush piles generate less heat and may be better for keeping your soils healthy. As always, plan your burning in a way that will reduce the risk of wildfire.

|

|

Brush piles should be no more than two metres high and three metres wide. The piles should be at least 10 metres from each other and at least 10 metres from the edge of the woods. It’s a good idea to burn no more than two piles at once. For large piles, industrial permits can be obtained from your local NSDNR office.

But do you really need to burn that brush pile? Where brush piles have been created, they often provide good wildlife habitat. Ground-dwelling birds such as ovenbirds, winter wrens, and white-throated sparrows use piles that are a year or two old. Mammals like meadow voles, snowshoe hare, chipmunks, and least weasels use brush piles for shelter and for hunting for food. Reptiles and amphibians congregate in brush piles where moisture is usually high and temperatures are cool. These include salamanders, newts, and garter snakes. In as little as two or three years, if left intact (and perhaps even built larger with fresh material), a brush pile is usually teeming with life.

Should you burn that brush pile? This question is an important one for property owners!

|

|

Burning Grass: A Spring Ritual

It is one of the scents of spring: the rich, pungent aroma of burning grass. Everyone seems to do it, from rural homeowners who burn their ditches and lawn edges to blueberry growers who burn grass and old growth from their plants to make way for new shoots.

There is something compelling about burning grass: torching the old to make way for the new, the green grass looking even greener against the blackened sod. But the fact is, aside from the visual appeal, burning grass can actually do more harm than good. First, the grass and other vegetation that could be returning to the soil as nutrients is instead literally going up in smoke.

Second, weeds that have seeded out the previous year are not likely to be destroyed by burning. They may come back thicker than ever, while grass coverage is actually reduced by up to half from burning. Weeds that have a knack for aggressively colonizing new sites will likely occupy areas left bare by burning.

|

|

Finally, you may be damaging wildlife habitat and the nests of birds, particularly when burning fields. Voles and mice rely on long grass and shrubs for shelter; burning the grass may displace them to less desirable locations (your house, for example). Raptors such as Northern harriers nest on the ground in open field and marshes, and landowners may not be aware that nests (and eggs or young) are even present. Burning a field can easily destroy a nest and its contents.

There are other risks associated with spring burning. If a fie gets out of control and escapes into woodland or adjacent properties, your costs of burning could rapidly escalate. Even with snow still present, spring burning of grass does not guarantee the fie will not spread. A light breeze can carry grass fies quickly and for long distances, even over —and under—patches of snow.

|

|

Following Regulations: Burning Restrictions

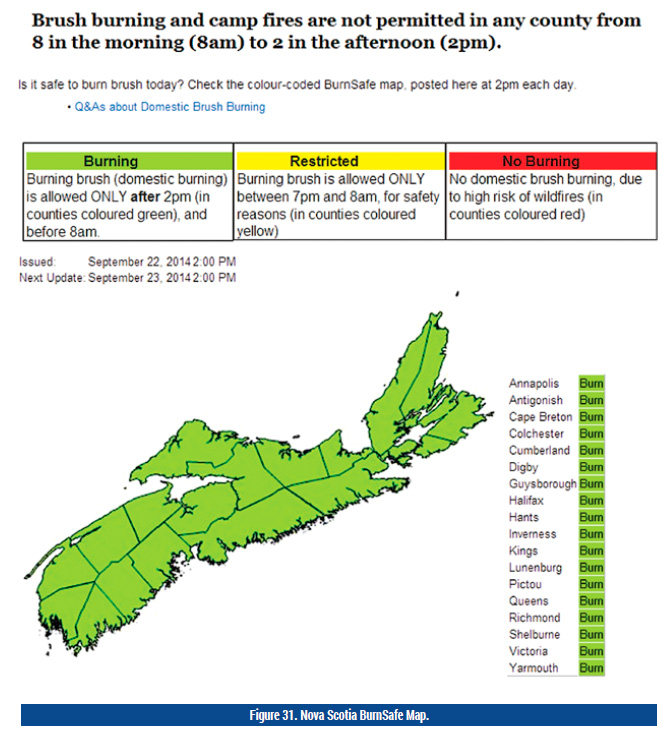

Domestic burning permits are no longer needed in Nova Scotia. Permits have been replaced by an online BurnSafe map, which must be consulted prior to burning. You can find this map at www.novascotia.ca/burnsafe.

To check whether there are any current burning restrictions in your areas, go to the NSDNR website. Even when the Fire Weather Index is low, there may be restrictions on brush burning and campfires.

Green, yellow, and red colour codes are used to indicate the levels of burning restrictions.

- Green: Burning brush (domestic burning) is allowed only between 2 pm and 8 am.

- Yellow: Burning brush is allowed only between 7 pm and 8 am.

- Red: No domestic brush burning due to high risk of wildfires.

It is important to note that there is no domestic brush burning between 8 am and 2 pm at any time during wildfie-risk season (March 15–October 15).

If you are clearing land for agriculture or development, industrial permits are required for brush piles larger than two metres high and three metres wide or for blueberry field larger than two hectares. These permits are available, for a fee, at your local NSDNR office. Its likely that a forest technician will visit the site prior to issuing a permit.The BurnSafe map must be referred to before beginning any brush burning in woodland or within 330 metres (1,000 feet) of woodland during wildfire-risk season (March 15–October 15).

|

|

Conclusion

Nearly everyone agrees that fires have both drawbacks and benefits.As a tool for clearing brush, for resetting forest ecosystems with a natural disturbance event, and for acting as a focus for social interaction, fie has long captured our imagination and respect. We cook with it, heat with it, and harness its power in many ways. The ecology of fie has long been the central character in human survival and progress.

When fie slips its leash and rages out of control, the human tendency is to step back (or run) and respect its appetite for destruction. As woodland owners, our properties contain the fuels that can transform a campfire into a firestorm.

Through prudent woodland management techniques and fie prevention efforts, we can stop wildfires before they begin. This module has outlined the steps that we can take to prevent and control woodland fires before they become wildfires. It is now our responsibility to step up and lay the vital foundations for wildfire-free woodland.

Module 16 - Quiz Lesson 4

| Questions: | 10 |

| Attempts allowed: | Unlimited |

| Available: | Always |

| Pass rate: | 75 % |

| Backwards navigation: | Allowed |

Lesson 8 - Case Study 2

Harold had felt pleased with himself. He had repaired the roof on his camp yesterday, just above where the squirrels had been making their way in and playing havoc with the plastic food containers in his cupboard. Some metal flashing had solved the squirrel problem, he hoped, and a half-dozen new shingles had sealed the deal. Now he hoped there would be no more leaks and even fewer squirrels in his small hunting camp.

Spring cleaning was a necessary chore. Harold didn’t use the camp much during the winter, except when some friends showed up on their snowmobiles and asked to use the camp for an overnight trip. He was happy to share, despite the squirrel problem.

His day had started by clearing some of the brush around the camp with his chainsaw—mostly small fir tees that had begun to encroach on the walls. He had worked at clearing brush all morning and the large pile of brush showed something for his efforts. Harold marvelled that there were still patches of snow in some places—it had been a fairly open winter and spring had seemed to come early.

Before setting out for his camp, Harold had checked with the local Department of Natural Resources office for a burnin permit. When he was told he didn’t need one, he wondered why, since he could always remember needing a permit once April arrived. The forest technician on duty had showed him a computer screen with the new BurnSafe map on it. Most of the province was coloured yellow, meaning Harold could burn after 7 pm and before 8 am at his camp property in Hants County. That was fine with him, since he was spending the weekend at the camp and this was only Thursday. Thanking the forest technician and promising her that he would recheck the map each day, Harold went on his way.

By Saturday Harold had cleared and piled the brush, and was looking forward to a quiet, restful Sunday. Both Friday and Saturday had been warm, windy days. He figued that things would soon start to green up in the woods.

He had a supper of fishcakes and beans before heading out to check the brush pile. Lots of brush to burn, he chuckled as he crumpled a newspaper and sparked his lighter. The paper caught the flame and crinkled as it burned. White smoke curled through the forest canopy as the flame flared and—just as promptly—died.

Well, thought Harold, he didn’t have much other paper apart from the essential kind in his little outhouse. He went over and picked up his fuel can, which was still half full of chainsaw gas. Liberally sprinkling the brush pile with gas, Harold once again flicked his lighter. Wow—that was better! With a roar, the pile erupted into flame, the fir needle snapping and sparking as they caught.

It took Harold less than two minutes to realize that he had made a mistake. The brush pile was quickly beginning to burn out of control. The dry carpet of leaves on the forest floor began burning in all directions and the flame soon reached other vegetation. Overhead, the shaft of rising heat and smoke created a current of wind that swirled among the softwood branches.

Harold wasn’t unprepared. He had a shovel handy and began swatting the escaping ring of fie, beating the leaves and shrubs that were now burning merrily. As soon as he had one side under control, another side would flare up, threatening to reach the surrounding softwood trees, which Harold had thinned just two years ago.

The brush pile was nearly consumed now, but there were other things to think about. A small fir tee caught fie, and another, sputtering and popping as the fie ate the dry needles. On the other side of the expanding circle of flame, the fie crept slowly toward the camp. Harold pounded the shovel furiously about him, realizing that the fie was getting well beyond his control.

Remembering something he had read in a booklet on forest fies, he started digging like a madman, prising the dark earth from the ground. He threw the soil on the fie, and one finger of flame disappeared. Harold continued, the sweat pouring down his face, his heart hammering, throwing soil as quickly as he could upon any flame he could see on the leading edge of the fie. Sweet mercy—he was gaining ground!

For the next 20 minutes, Harold alternated between swatting flames and smothering them with soil. Once or twice a smouldering clump of leaves would flare up and threaten to spread, but he reached them in time. Anywhere he could see smoke he threw soil, extinguishing the embers before they became flame.

Exhausted beyond measure, Harold leaned on his shovel and looked around. Blackened leaves were practically beneath his camp walls. On the other side the flames had stopped mere metres from his thinning; with the dry cut underbrush, the fie would have raced through the thinning. From there it was only a short distance to his neighbour’s property and hunting trailer; beyond that, a hundred acres of softwood and then a dozen houses. Good grief. So close to disaster, he thought.

To make sure there were no orphan embers, Harold walked through the brush and trees around his camp in expanding circles. He saw where one flying burning leaf had landed and now lay slowly smoking near an old stump. Harold put two shovelfuls of soil on it, just to be sure.

He realized now that over the past two days, the Fire Weather Index had risen beyond the yellow zone and into the red zone, on the map the forest technician had shown him. Harold knew he should have paid more attention to the clues around him, particularly to the warm breezy weather. He knew he should have checked the BurnSafe map again, before he ever lit the fire.

Harold was grateful he had had a shovel handy, but he knew he should have had more fie control tools at hand. A back tank ideally, a bucket of water or two at the very least. But the gear would not have been necessary if he had gauged the situation more closely. Much of what he should have done was only common sense, Harold concluded.

A rumble in the distance made him glance skyward: rain tonight. I could sure use that, he thought.