Module 1: Introduction to Silviculture

‘Introduction to Silviculture’ explains the importance of forestry and it reviews the basic characteristics of trees, stand growth and development essential to understanding forest management activities. Where possible, technical forestry terms have been avoided, although in some cases their use is necessary for clarity. All terms in italics can be found in the glossary at the end of the module.

‘Introduction to Silviculture’ is part of the Woodlot Management Home Study Course Series. This series is designed to help woodlot owners understand and practice integrated resource management. The Home Study Course offers flexible, accessible learning and provides owners with a lasting reference. This series is intended to help you understand the concepts of good forest management as they apply to your woodlot. Because forest management is such a broad topic, this series is divided into several study modules.

‘Introduction to Silviculture’ was originally produced as a co-operative effort between the Canadian Forestry Service and the Department of Lands and Forests in 1987 and has been updated in 1994 and 2005. Tree identification illustrations have been used with the permission of InterFor, New Brunswick. The original text was written by LaHave Forestry Consultants Ltd. with editorial help from Lands and Forest and Canadian Forestry Service staff.

We sincerely hope that you enjoy and benefit from the material presented.

Lesson One - Introduction

Importance of Our Forests and the Forest Industry

Diverse, healthy forests are vital to the well being of our planet. Forests are complex, living systems that are home to a variety of organisms. They protect our soils, rivers and lakes and are a valuable recreational resource. Even the quality of the air we breathe depends, to a great extent, on forests. Trees store carbon and absorb carbon dioxide (especially fast growing ones), thereby reducing the greenhouse effect.

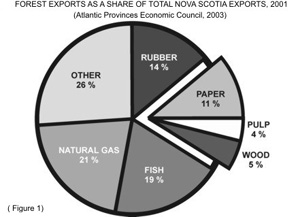

Economically, the forest industry is vital to Canada and Nova Scotia. (Figure 1) Nationally, in 2003, the industry contributed over $33 billion to the gross domestic product; almost $40 billion to our exports; and $29.7 billion to our balance of trade (Natural Resources Canada, 2004).

Provincially, in 2003, forestry contributed to our economy through more than $923 million in exports; and over $873 million to our balance of trade. Over 13,000 jobs result directly from the forestry industry in Nova Scotia (Natural Resources Canada, 2004).

To maintain this industry, approximately 6 million cubic meters (m3) of roundwood is harvested each year in the province (Natural Resources Canada, 2004). Sixty percent of this wood comes from small private woodlots, which cover 50% percent of the forested land base in Nova Scotia. The land is owned by over 31,000 small landowners (Dansereau & deMarsh, 2003, Canadian Institute of Forestry, 2001).

The forest has provided Nova Scotians with a way of life for many generations. If we are to maintain a healthy productive forest in the future, it is important that everyone understand the forest and practice sustainable forest management.

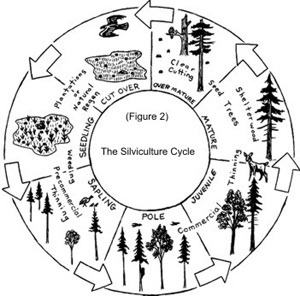

Understanding trees and how they grow is basic to the practice of silviculture. Silviculture is the practice by which stands are tended, harvested and replaced by new stands to meet specified objectives. It includes the “green circle” from artificial regeneration or natural regeneration to harvesting (Figure 2).

The intent of this module is to help readers understand some basic characteristics of tree species which are important to the practice of silviculture. It does not discuss silviculture techniques, or the related subject of forest ecology; these are dealt with in modules 2,3,5 and 7 respectively.

The Forest of the Past

As the original inhabitants of this province, the Mi’kmaq, occupied most of the land prior to the arrival of the European settlers. The First Nations people had a unique relationship to the earth’s resources, engaging in various life-supporting activities, ranging from hunting and gathering, to agricultural activities. They believed that the richness of the earth was provided by their Creator. The Aboriginal peoples assumed a role of stewardship and pursued their activities guided by principles of respect and responsibility to the land and natural resources (NSDNR, Education Module).

The first Europeans had a different view of the seemingly endless forest of pine, spruce, hemlock and majestic hardwoods. They saw the forest as something that had to be conquered if they were to survive.

The same forest that initially presented an obstacle to the survival and success of the new settlers soon became a source of wealth. The best white pine trees were cut and exported to supply the world shipbuilding industry. Later, the demand for spruce and hemlock lumber fed the local and export markets. When the supply of sawlogs dwindled, pulp mills were established and areas previously cut were recut. Each time the forest was cut, only the biggest and best trees were taken. The removal of the very best trees is called selective harvesting or high-grading and was a common practice. In many cases, only the poor quality trees were left. Since these trees were the main seed source, they tended to produce poor quality, sparse stands of low volume.

The attitude of most people at that time was that the supply of wood was endless. It didn’t take long before the forests of Nova Scotia consisted of poor quality trees. A study conducted by Fernow (a noted forester) in 1909-1910 concluded that the forest was:

“largely in poor condition, and is being annually further deteriorated by abuse and injudicious use because those owning it are mostly not concerned in its future and do not realize its potentialities”.

Disturbances like fire and insect outbreaks have also shaped our forest. Fires, like those caused by lightening, are a natural part of the forest ecosystem. During the early 1900’s, fire was used to clear land. These fires accidentally spread into the surrounding forest and destroyed thousands of acres of merchantable timber. A fire prevention and suppression program began in 1927, when the amount of damage caused by these man-made fires was realized. Trees are also susceptible to insects and disease. While they are a natural occurrence, they can adversely affect the economic quality of our forest.

Clearcutting began in the late 1960’s and 1970’s with the introduction of mechanical logging equipment (Johnson, 1986). While it is an appropriate harvesting system in some forests, clearcutting was often not done properly and has produced some poor quality forests. It removes all merchantable trees from an area at the same time. Large clearcuts tend to regenerate with species, such as trembling aspen, pin cherry, and red maple. These species have less economic value and are the pioneer species of the Acadian Forest.

Woodlands were not always properly managed in the past because settlers lacked the knowledge; there were few established guidelines, and there was limited revenue. Many operators were simply unaware of the long-term effects of high-grading. Minimal returns on stumpage did not encourage reinvestment in the forest, and legislative guidelines for harvesting methods were not enforced.

The Forests of Today

Nova Scotia is located in the Acadian Forest Region of Canada. This is a relatively small region covering nearly all of Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and southern New Brunswick. It is a transition zone between the southern deciduous forest and the coniferous forest to our north (Farr, 2003). The Acadian Forest is characterized by a variety of coniferous and deciduous tree species. In all there are 30 tree species that are native to the Acadian Forest (Saunders,1995).

The demand for forest products has increased significantly over the past ten years. This has lead to significant harvest increases, especially on private lands (NSDNR, 1997). With approximately 50% of the productive forest in private ownership, it is essential that woodlot owners practice good management, for wood production, biodiversity, wildlife, water quality, recreation and other values.

The provincial government recognized the values of private woodlots in its 1986 ‘Forestry Policy’. This policy “encouraged the development and management of private forest lands as the primary source of timber for industry in Nova Scotia” while ensuring owners “continued to enjoy the traditional rights and responsibilities of private ownership of land.”

In 1997, the provincial government produced ‘Toward Sustainable Forestry: A Position Paper’ to reflect evolving values and concerns, as well as society’s changing needs and expectations for stainable development. The ‘Forest Sustainability Regulations’, enacted in 2000, require certain forestry companies, based on their annual volume of wood acquired, to undertake annual silviculture work on private land. (Private land means all lands excluding Crown land.) Companies can meet the requirements of these regulations by carrying out a silviculture program on private lands, by contributing money to a special fund called the Sustainable Forestry Fund, or some combination of both. The intent of the new regulation is to increase the amount of silviculture work on private lands (NSDNR, 2000a).

The total gross merchantable volume for all species in Nova Scotia is 404 million cubic metres (168 million cords). Of this, 70% is softwood (282 million cubic metres or 118 million cords) and 30% is hardwood (122 million cubic metres or 50 million cords) (Townsend, 2004). Harvesting on Crown and industrial lands has remained within potential wood supply limits while softwood harvesting on small-private woodlots has increased in recent years (Atlantic Provinces Economic Council, 2000). As a result of the Forest Sustainability Regulations, increased silviculture should be able to offset this rise in harvest level.

Because the best land was granted to the public, small private woodlots tend to have a higher net growth rate than those of Crown lands. Therefore, silvicultural investment on private woodlots usually generates a relatively higher return. The average growth rate for Nova Scotia forests is 2.0 cubic metres per hectare per year (0.9 cords per acre per year). With the use of appropriate silviculture, this growth can be increased to an estimated 5.5 m3/ha/yr. (2.5 cd/ac/yr)(NSDNR, 2000b).

A combination of knowledgeable, committed land owners, cash incentives for silviculture programs, tax incentives, public education, legislation, and increased wood prices are necessary for well managed woodlots. Past winners of the Woodlot Owner of the Year Program provide evidence that N.S. has keen and knowledgeable woodlot owners. Cash incentives are being provided by Provincial and industry programs, such as the Forest Sustainability Regulations. These home study modules and similar courses help landowners learn more about forest management and legislation such as the Wildlife Habitat and Watercourse Protection Regulations ensure valuable habitat is protected on all land.

The Future Forest

Depending on species, a forest may take 40 to 100 years to mature. Consequently, we must practice sound management today to ensure productive and healthy forests for our children.

We must harvest with the future in mind. This means leaving the best trees as a seed source so that new trees are of good quality and health. This means ensuring there are adequate buffers along water ways. It also means managing for a variety of species, because a diverse ecosystem is stable and is better able to handle disturbances. These are some of the aspects woodlot owners must address when deciding how best to manage their land to meet the needs of society and woodlot owners today, and the needs of future generations.

Proper forestry practices must be the concern of everyone regardless of whether or not they work in the forest industry. We have used our forest to build a great nation. Now it is time to ensure the future forest is managed for a variety of values, species and age classes. Through education, financial incentives, tax incentives and appropriate legislation, diverse healthy forests will be sustained.

Module 1 - Lesson One Quiz

| Questions: | 10 |

| Attempts allowed: | Unlimited |

| Available: | Always |

| Pass rate: | 75 % |

| Backwards navigation: | Allowed |

Lesson Two - Softwood Tree Identification and Silvics

To practice silviculture in Nova Scotia it is essential to recognize common trees. Once a tree is identified you can understand its rooting habit, windfirmness, associated species, favored growing sites and shade tolerance. With this information you can make an informed decision about the trees on your woodlot. For more information about common trees in Nova Scotia consult Trees of Nova Scotia (Saunders, 1995).

Lesson Two and Three briefly discuss soil types and characteristics. More information on soils can be found in Module 7 (Woodlot Ecology). For help in determining the type of soil on your woodlot consult the Forest Ecosystem Classification Guide published by the Nova Forest Alliance (Keys et al. 2003) listed in the ‘Further Reading’ section of this module.

This lesson presents the silvics and field identification characteristics of softwood trees in Nova Scotia. The section entitled “Average Mature Trees” has been included as a rough guide to help with identification. An average tree does not exist.

Silvics of Balsam Fir

|

SILVICS OF BALSAM FIR

(Abies balsamea (L.) Mill.)

Common names:

- fir, balsam, Canada balsam

Field identification aids:

- only native softwood with resin blisters on the bark that exude a sticky resin

- typical Christmas tree smell (balsam)

- flat needle does not roll easily between fingers

- tip of needle is blunt

- needles are dark, shiny green above with two white lines underneath

- Shoots are soft when squeezed

- only native conifer with upright cones

Average mature tree:

- 40 to 50 years old

- 12 m to 18 m (40' to 60') tall

- 20 cm to 36 cm (8" to 14") in diameter at breast height

Maximum life span:

- 150 years

Shade Tolerance:

- very tolerant

Rooting:

- shallow, wide-spreading roots

Windfirmness:

- not windfirm

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seed

- tree may begin to produce seed as early as 15 years old with full crop production after 30 years

- good crops can be expected every 2 to 4 years

- best seed germination occurs on moist mineral soils or humus

Growing sites:

- adaptable to a variety of soils

- best growth on moist and well-drained sites

Associated Species:

- forms pure stands on poorly-drained sites

- grows in association with almost all native trees

- most commonly found with spruces, hemlock, birch and aspen.

Principal damaging agents:

- spruce budworm, balsam woolly adelgid, white tussock moth, hemlock looper, balsam fir sawfly, porcupines

Notes:

- balsam fir comprises 17.9% of the merchantable volume in Nova Scotia

- principal Christmas tree species due to high needle retention

- after about 40 years old, fir tends to develop butt rot that reduces its value as pulpwood and logs

- often regenerates in abundance after clearcutting

|

Quick ID:

Balsam fir has soft needles 'Fir is Friendly' |

|

|

|

Silvics of Black Spruce

|

SILVICS OF BLACK SPRUCE

(Picea mariana (Mill.) B.S.P.)

Common names:

- bog spruce, swamp spruce, red spruce

Field identification aids:

- usually the only spruce growing in bogs or swamps

- grey-green to blue-green, blunt-pointed, four-cornered needles that can roll between your fingers

- usually the only spruce growing in bogs or swamps

- inner bark is olive green

- retains spherical brown cones for many years

- forms a definite clump of short branches at tip of crown. In older trees this clump carries numerous old cones

- brownish, hairy twigs; otherwise quite similar to those of red spruce

Average mature tree:

- 70 to 90 years old

- 9 m to 15 m (30' to 50') tall

- 15 cm to 25 cm (6" to 10") in diameter at breast height

Maximum life span:

- 200 years

Shade Tolerance:

- medium

Rooting:

- shallow, spreading root system

Windfirmness:

- shallow rooted and easily blown over

Reproduction:

- can reproduce through seed or by layering

- heavy cone drops every 4 years

Growing sites:

- ranges from wet to well drained sites

- best growth is on moist, well-drained loamy soils

- usually grows on poorly-drained soils

Associated species:

- white spruce and balsam fir on good sites

- on poor sites usually grows in pure stands or associated with tamarack

Principal damaging agents:

- spruce budworm, eastern dwarf mistletoe, European spruce sawfly

Notes:

- black spruce comprises 3.7 % of the merchantable volume in Nova Scotia

- interbreeds easily with red spruce and they are difficult to tell apart

- has sealed cones that require heat to open

- first conifer to establish after a fire

|

Quick ID:

Black spruce has a clump of short branches on top |

|

|

|

Silvics of Eastern Hemlock

|

SILVICS OF EASTERN HEMLOCK

(Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carr.)

Common names:

- tree juniper, white hemlock

Field identification aids:

- needles are small, dark shiny green, blunt tipped, with two white lines underneath

- bark is purplish-brown when scraped

Average mature tree:

- 100 to 140 years old

- 18 m to 21 m (60' to 70') tall

- 60 cm to 122 cm (24" to 48") in diameter at breast height

Maximum life span:

- 600 years

Shade tolerance:

- very tolerant

Rooting:

- wide-spreading, shallow root system

Windfirmness:

- moderately windfirm

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seed

- begins to produce seed as early as 20 with full production after 50 years

- good cone crop every 2 to 3 years

- best germination is on shaded cool sites

Growing sites:

- grows on a wide range of soils, as long as it is shaded and cool

Associated species:

- white pine, red spruce, yellow birch, sugar maple

- occasionally occurs in pure stands

Principal damaging agents:

- hemlock looper, porcupines, and windstorms

- wind causes cracks between growth rings in larger trees, this may increase heart rot

Notes:

- hemlock comprises 2.8% of the merchantable volume in Nova Scotia

- bark is often riddled with woodpecker holes

- splits easily, but is durable when used in large dimensions

|

Quick ID:

Hemlock needles are on short stalks that come off with the needle |

|

|

|

Silvics of Jack Pine

|

SILVICS OF JACK PINE

(Pinus banksiana Lamb.)

Common names:

- princess pine, scrub pine, grey pine

Field identification aids:

- needles are light yellow-green, two per cluster forming a “V”

- cones point toward end of branch

- cones are strongly curved

- retains cones for years, even after tree is cut

- dead branches remain on tree giving it a scraggy appearance

Average mature tree:

- 50 to 60 years old

- 12 m to 20 m (40' to 67') tall

- 20 cm to 30 cm (8" to 12") in diameter at breast height

Maximum life span:

- 150 years

Shade Tolerance:

- intolerant

Rooting:

- moderately deep and wide-spreading

- produces a tap root on deep porous soils

Windfirmness:

- windfirm, but prone to mechanical breakage

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seed

- will begin to produce seed as early as 10 years with full production at 40 years

Growing sites:

- range from dry to poorly-drained soils

- best growth is on sandy, well-drained soils

Associated species:

- black spruce, white birch and aspen

- can be found in pure stands

Principal damaging agents:

- porcupines

Notes:

- jack pine comprises less than 1% of the merchantable volume in Nova Scotia

- generally used for railway ties, poles and fuelwood

- often establishes after a fire, particularly on poor sites

|

Quick ID:

Jack pine is the only native pine with two short needles. It also has strongly curved cones |

|

|

|

Silvics of Red Pine

|

SILVICS OF RED PINE

(Pinus resinosa Ait.)

Common names:

- Norway pine, bull pine

Field identification aids:

- has the longest needles of pines with two needles per cluster

- needles break in two when bent

- bark on older trees breaks off in flat red-brown plates

Average mature tree:

- 60 to 70 years old

- 18 m to 25 m (60' to 80') tall

- 30 cm to 60 cm (12" to 24") in diameter at breast height

Maximum life span:

- 200 years

Shade Tolerance:

- intolerant

Rooting:

- moderately deep and wide-spreading

Windfirmness:

- moderate to good depending on soil depth

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seed

- tree may begin to produce seed at 20 with full production after 50 years

- good seed crop every 3-7 years, with a bumper crop every 10-12 years

- germination best on moist humus mineral mixture

- poor germination on heavy litter

Growing sites:

- will grow on soils too poor for white pine

- best growth is on well-drained sandy soils

Associated species:

- white pine and jack pine

- occasionally grows in pure stands

Principal damaging agents:

- Sirococcus shoot blight, European pine shoot moth

- prone to mechanical breakage and browsing from white tail deer

Notes:

- red pine comprises less than 0.5% of the merchantable volume in Nova Scotia

- sturdy, rot resistant wood makes it ideal for power poles and wharf and bridge pilings

|

Quick ID:

only native pine with 2 long needles |

|

|

|

Silvics of Red Spruce

|

SILVICS OF RED SPRUCE

(Picea rubens Sarg.)

Common names:

- yellow spruce, Maritime spruce

Field identification aids:

- bright yellow-green, blunt, four-cornered needles that can roll between your fingers (needles are usually longer than those on black spruce)

- reddish bark on young trees orange-brown and slightly hairy twigs

- Large broad crown, with right angled branches that curve upward near the ends

- red and black spruce interbreed and are often difficult to tell apart

Average mature tree:

- 80 to 100 years old

- 21 m to 26 m (70' to 86') tall

- 30 cm to 60 cm (12" to 24") in diameter at breast height

Maximum life span

- 200 - 400 years

Shade tolerance:

- very tolerant

Rooting:

- shallow and widespread

Windfirmness:

- only moderately windfirm on most Nova Scotian sites, susceptible to wind damage

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seed

- tree may begin to produce seed when 20 to 30 years old, with full crop production usually after 45 years

- good cone crops every 3 to 8 years

- best germination occurs on a moist mixture of mineral soil and humus

- poor germination on thick duff

Growing sites:

- range from well-drained to poorly drained

- best growth is on well -drained, acidic sandy soil

- usually found on moderately drained soils

Associated species:

- black spruce, balsam fir, tamarack, and red maple on poorly drained sites

- sugar maple, yellow birch, beech, and balsam fir on well drained sites

- often found in pure stands

Principle damaging agents:

- spruce budworm, spruce bark beetle, brown spruce longhorn beetle, porcupines

Notes:

- red spruce comprise 22.8% of the merchantable volume in Nova Scotia

- the most valuable lumber and pulpwood species in Nova Scotia

- Nova Scotia’s provincial tree

|

Quick ID:

Red spruce branches curve upwards |

|

|

|

Silvics of Tamarack

|

SILVICS OF TAMARACK

(Larix laricina (Du Roi) K. Koch.)

Common names:

- larch, juniper (not a true juniper), hackmatack

Field identification aids:

- has smallest cone of native conifers

- many needles in a cluster

- soft, blue-green needles that turn yellow in autumn

Average mature tree:

- 50 to 70 years old

- 12 m to 20 m (40' to 67') tall

- 30 cm to 60 cm (12" to 24") in diameter at breast height

Maximum life span:

- 150 years

Shade tolerance:

- very intolerant

Rooting:

- shallow and wide-spreading

Windfirmness:

- moderately windfirm

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seed

- occasionally reproduces by layering

- will bear seed as early as 12 years old with full production after 40 years

- best germination on moist mineral or organic soil with light cover

- good cone crop every 3 to 6 years

Growing sites:

- range from upland sites to bogs

- best growth is on well-drained soils with very little clay (light soils)

- usually found on wet sites

Associated species:

- black spruce and red maple on poor sites

- on better sites occurs with trembling aspen, white birch and balsam fir

Principal damaging agents:

- larch sawfly, larch casebearer, white-marked tussock moth, and porcupines

Notes:

- tamarack comprises 1.7% of the merchantable volume in Nova Scotia

- fastest growing softwood on a good site

- characteristic tree of swamps and bogs

- very durable for outdoor projects

|

Quick ID:

Tamarack losses its needles in the autumn |

|

Silvics of White Pine

|

SILVICS OF WHITE PINE

(Pinus strobus L.)

Common names:

- eastern white pine, soft pine, pattern pine, yellow pine, majestic pine

Field identification aids:

- only native five-needled pine

- needles are blue-green, long and soft to touch

- cigar shaped cones that are longer than those of other native pines

Average mature tree:

- 100 to 120 years old

- 24 m to 30 m (80' to 100') tall

- 601 cm to 90 cm (24" to 36") in diameter at breast height

Maximum life span:

- 200 - 450 years

Shade Tolerance:

- medium

Rooting:

- moderately deep, wide-spreading root system

- will produce a token tap root where soil permits

Windfirmness:

- moderately windfirm, more likely to break off than uproot

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seeding

- may produce seed as young as 20 with full crop production at 50 years

- good seed crop production every 3 to 5 years

- best germination occurs on exposed moist sandy loam

- litter is a poor seed bed for white pine

Growing sites:

- range from dry rocky sites to poorly drained sites

- best growth is on moist, loamy sands

Associated species:

- on poorly drained soils with black spruce and larch

- jack pine and red pine on dry sites

- hemlock, red spruce, yellow birch and sugar maple on well drained sites

Principal damaging agents:

- white pine blister rust, white pine weevil, redheaded pine sawfly, white-tailed deer

Notes:

- white pine comprises 8.3% of the merchantable volume in Nova Scotia

- many of the large trees standing above the rest in the forest are residual white pine

- the tallest and most stately of the eastern softwoods

- highly prized for interior finish

- straight grained, even textured, durable, light weight wood that takes nails, planing and painting well

|

Quick ID:

W-H-I-T-E = 5 needles on white pine |

|

|

|

Silvics of White Spruce

|

SILVICS OF WHITE SPRUCE

Picea glauca (Moench) Voss)

Common names:

- pasture spruce, skunk spruce, cat spruce

Field identification aids:

- blue-green, sharp-pointed, four-cornered needles that can roll between your fingers

- crushed needles have a rank odour similar to cat urine

- hairless twigs

- occurs commonly in old fields

- has thick branches that extend to ground

- inside bark is silvery white

Average mature tree:

- 50 to 60 years old

- 18 m to 24 m (70' to 80') tall

- 30 cm to 60 cm (12" to 24") in diameter at breast height

Maximum life span:

- 200 years

Shade tolerance:

- intolerant

Rooting:

- shallow and wide-spreading

Windfirmness:

- moderately windfirm on most Nova Scotian sites

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seeds

- tree may begin to produce seed when approximately 30 years old, with full production around 60 years

- good seed crop production every 2 to 6 years

- best seed germination occurs on well to moderately-drained soil

Associated species:

- black spruce and balsam fir on poorly-drained sites

- white birch and trembling aspen on well-drained sites

Growing sites:

- range from well drained to moderately-drained soils

- optimum growth is on moist, well-drained, sandy soils

- usually found on moderately-drained sandy loams

Principal damaging agents:

- spruce budworm, spruce beetle, eastern dwarf mistletoe, and porcupines

Notes:

- white spruce comprises 7.2% of the merchantable volume in Nova Scotia

- commonly found on old pasture land and has thick live branches that extend to the ground

- fastest growing spruce native to Nova Scotia

- usually selected as the Christmas tree sent to Boston each year, but has an unpleasant odour and needles drop quickly once cut

|

Quick ID:

White spruce has sharp needles 'Spruce is Sharp' |

|

|

|

Module 1 - Lesson Two Quiz

| Questions: | 10 |

| Attempts allowed: | Unlimited |

| Available: | Always |

| Pass rate: | 75 % |

| Backwards navigation: | Allowed |

Lesson Three - Hardwood Tree Identification and Silvics

This lesson introduces the common hardwoods of Nova Scotia.

Silvics of Beech

|

SILVICS OF BEECH

(Fagus grandifolia Ehrh.)

Common names:

- American beech

Field identification aids:

- beech retain their leaves through most of the fall and early winter

- buds are long with sharp ends

Average mature tree:

- 60 to 80 years old

- 12 m to 21 m (40' to 70') tall

- 20 cm to 60 cm (8" to 24") in diameter at breast height

Shade tolerance:

- very tolerant

Windfirmness:

- moderately windfirm

Rooting:

- shallow, wide spreading lateral roots

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seed, stump sprouting, or suckering from exposed roots

- tree may begin to produce seed when 40 years old, with full crop production after 60 years

- good seed crop produced every 2 to 3 years

- best seed germination occurs on moist humus or mineral soil

- poor seed germination on wet sites

Growing sites:

- range from moderately drained to well-drained

- best growth on well-drained loam sites

Associated species:

- red maple, sugar maple, yellow birch, red spruce, and hemlock on well drained sites

- rarely found in pure stands

Principal damaging agent:

- beech bark disease (insect-fungal partnership)

Notes:

- comprises 1.1% of merchantable volume of Nova Scotia forests

- a decrease in quality of beech due to heavy damage sustained by beech bark disease.

- used primarily for fuelwood

|

Quick ID:

The trunk and branches of beech are often gnarled and crooked from beach bark disease |

|

|

|

Silvics of Grey Birch

|

SILVICS OF GREY BIRCH

(Betula populifolia Marsh.)

Common names:

- wire birch, white birch

Field identification aids:

- triangular leaves

- warty, wire-like twigs

- tight, non-peeling, greyish bark

Average mature tree:

- 30 to 50 years old

- 6 m to 11 m (20' to 35') tall

- 8 cm to 12 cm (3" to 5") in diameter at breast height

Shade tolerance:

- intolerant

Rooting:

- shallow laterals, no tap root produced

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seed or stump sprouting

- full seed crop production after 30 years, good seed crop every year

- best germination occurs on moist, mineral soil

Growing sites:

- range from dry to poorly-drained, best growth on well-drained sites

- usually found on recent clearcuts, burnt areas, and old fields

Associated species:

- alders and larch on poorly drained sites

- white birch, pin cherry and aspen on well drained sites

- often grows with red spruce

- occasionally found in pure stands

Principal damaging agents:

- nectria canker, birch leaf skeletonizer, birch sawfly, bronze birch borer

Notes:

- not a commercial species, but can be used for fuelwood

|

Quick ID:

Grey birch has black, triangular markings where branches join the trunk |

|

|

|

Silvics of Largetooth Aspen

|

SILVICS OF LARGETOOTH ASPEN

(Populus grandidentata Michx.)

Common names:

- aspen, poplar, bigtooth aspen

Field identification aids:

- large teeth around the entire edge of leaf

- smooth green bark when immature; dark grey and furrowed when older

Average mature tree:

- 40 to 60 years old

- 12 m to 18 m (40' to 60') tall

- 30 cm to 48 cm (12" to 18") in diameter at breast height

Maximum life span:

- 60 years

Shade tolerance:

- very intolerant

Rooting:

- shallow spreading lateral roots

Windfirmness:

- not wind firm

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seed, sprouting, and by suckering of roots

- tree may begin to produce seed as early as 20 years old, with full crop production after 30 years

- good seed crop every 4 to 5 years

- best seed germination occurs on moist mineral soil under full sunlight

Growing sites:

- range from moderately drained to dry

- best growth on well-drained loam soils

- usually found on recent cutovers and burned sites

Associated species:

- trembling aspen, white birch, grey birch, pin cherry, white spruce, and balsam fir on well drained soils

- occasionally found in pure stands

Principal damaging agents:

- hypoxylon canker, forest tent caterpillar, satin worm

Notes:

- largetooth aspen comprises 1.2% of the merchantable volume in Nova Scotia

- short-lived tree that is capable of rapid growth on favorable sites

- wood can be used for pulpwood, pallets, and fuelwood

|

|

|

|

Silvics of Pin Cherry

|

SILVICS OF PIN CHERRY

(Prunus pensylvanica L.F.)

Common names:

- fire cherry, hay cherry, red cherry, bird cherry

Field identification aids:

- small tree that rarely exceeds 8 m (25') tall

- bark of young cherry resembles that of young birch sapling

- bark of older cherry is dotted with light brown markings

- buds smell like almonds when crushed

- berry is sour tasting

Average mature tree:

- 20 to 30 years old

- 3 m to 8 m (10' to 25') tall

- 10 cm to 15 cm (4" to 6") in diameter at breast height

Shade tolerance:

- very intolerant

Rooting:

- moderately deep and wide-spreading

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seed

- seed is heavy and is dispersed by birds

- seed remains viable in the soil for long periods

Growing sites:

- occurs on burned areas, along rivers, and fence rows

- prefers sandy soil

- cutovers

Associated species:

- white and grey birch, trembling aspen, and alder

Principal damaging agent:

- black knot fungus

Notes:

- pin cherry is not a commercial species

- favorite food for birds

- twigs and leaves contain cyanic acid and are poisonous

- a pioneer species

|

Quick ID:

Pin cherry has black wart like cankers from black knot fungus |

|

|

|

Silvics of Red Maple

|

SILVICS OF RED MAPLE

(Acer rubrum L.)

Common names:

- soft maple, white maple, swamp maple

Field identification aids:

- sharp corner on leaf margin between lobes

- twigs are a deep red, often with branching perpendicular to main branch

- blunt buds (sugar maple buds are smaller and sharp)

Average mature tree:

- 50 to 60 years old

- 18 m to 22 m (60' to 70') tall

- 30 cm to 46 com (12" to 18") in diameter at breast height

Maximum life span:

- 100 years

Shade tolerance:

- medium

Rooting:

- shallow, wide-spreading lateral roots, occasionally with a small tap root

Windfirmness:

- moderately windfirm

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seed, stump sprouting, and suckering

- tree may begin to produce seed when 30 years old, with full crop production after 40 years

- good seed crop production almost every year

- best germination on a moist mineral soil with light leaf cover

Growing sites:

- range from poorly-drained to dry upland site

- best growth is on well-drained sites

- usually grows on moderately-drained soils, but are very common around swamps

Associated species:

- black spruce and balsam fir on poorly drained sites

- balsam fir , red spruce and yellow birch on well drained sites

- rarely found in pure stands

Principal damaging agents:

- gypsy moth, forest tent caterpillar, fall cankerworm, maple leaf cutter

- deer, moose and rabbit browsing

Notes:

- red maple comprises 14.9% of the merchantable volume in Nova Scotia forests - an increasing component of mixedwood stands due to regular seed production, ease of sprouting, medium tolerance, and continued partial cutting

- branches are prone to breakage during winter storms

- saplings are split and used to make baskets

- can be used to produce maple syrup

|

Quick ID:

The leaf margins have many teeth 'Red is Rough' |

|

|

|

Silvics of Red Oak

|

SILVICS OF RED OAK

(Quercus rubra L. )

Common names:

- oak, northern red oak

Field identification aids:

- only oak native to Nova Scotia

- dark green leaves with 7 to 11 bristle-tipped lobes

- large, sturdy tree that bears acorns

- cluster of buds at top of twig

Average mature tree:

- 70 to 90 years old

- 15 m to 21 m (50' to 70') tall

- 30 cm to 75 cm (12" to 30") in diameter at breast height

Maximum life span:

- 200 - 300 years

Shade tolerance:

- medium

Rooting:

- deep spreading lateral roots with a tap root

Windfirmness:

- good windfirmness on average sites

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seed or stump sprouting

- tree may begin to produce by seed when 25 years old, with full crop production after 50 years

- good seed crop production every 2 to 5 years

- best seed germination occurs on moist soil covered by litter

- poor germination on dry or exposed soil

Growing sites:

- range from deep stone free to shallow, rocky sites

- best growth is on fine textured soils with a high water table

Associated species:

- aspen, white birch and red maple on poor sites

- sugar maple, yellow birch, white ash, red spruce, red pine, and white pine on good sites

- can occur in pure stands, especially in Queens County

Principal damaging agents:

- gypsy moth, oak leaf-shredder, fall cankerworm, leaf skeletonizer

Notes:

- red oak comprises 0.9% of the merchantable volume in Nova Scotia

- wood used for flooring, interior finish and furniture

|

|

|

|

Silvics of Sugar Maple

|

SILVICS OF SUGAR MAPLE

(Acer saccharum Marsh.)

Common names:

- rock maple, hard maple

Field identification aids:

- new shoots are light brown or rust colored (red maple shoots are dark red)

- buds are opposite and sharp pointed (red maple has blunt buds that are much larger)

- leaf edge has fewer teeth than red maple leaves

- graceful branching (red maple branching is more irregular)

Average mature tree:

- 100 to 120 years old

- 24 m to 27 m (80' to 90') tall

- 30 cm to 60 cm (12" to 24") in diameter at

breast height

Maximum life span:

- 200 - 300 years

Shade tolerance:

- tolerant

Rooting:

- deep and wide-spreading

Windfirmness:

- windfirm

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seed, stump sprouting and to some extent root suckering

- tree may begin to produce seed when 40 to 60 years old, with full crop production after 70 to 100 years

- good seed crop production every 2 to 5 years

- best seed germination occurs on moist, mineral humus mixture

- has the unique ability to reproduce on undisturbed forest litter

Growing sites:

- range from well-drained to dry

- best growth is on deep fertile, well-drained moist loam soil

- usually found on well-drained upland soils

Associated species:

- usually found with beech, yellow birch, and red spruce on good sites

- occasionally found in pure stands

Principal damaging agents:

- sugar maple borer, gypsy moth, forest tent caterpillar, and fall cankerworm

Notes:

- sugar maple comprises 4.6% of the merchantable volume in Nova Scotia

- young shoots are heavily-browsed by deer

- best tree for producing maple syrup

- wood is excellent for flooring, furniture, interior finishing, veneers, sporting goods, and musical instruments

- a majestic shade tree

|

Quick ID:

The leaf margin between lobes is smooth ' Sugar is Smooth' |

|

|

|

Silvics of Trembling Aspen

|

SILVICS OF TREMBLING ASPEN

(Populus tremuloides Michx.)

Common names:

- aspen, poplar, popple, quaking aspen

Field identification aids:

- finely serrated leaf margin

- leaves turn yellow in fall

- leaf stem is often longer than the leaf itself

- bark on younger trees is smooth, pale green, but becomes grey and furrowed with age

Average mature tree:

- 40 to 60 years old

- 12 m to 18 m (40' to 60') tall

- 25 cm to 40 cm (10" to 16") in diameter at breast height

Maximum life span:

- 80-90 years

Shade tolerance:

- very intolerant

Rooting:

- shallow, lateral roots

Windfirmness:

- commonly uprooted

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seed, sprouting, and suckering of roots

- tree may begin to produce seed when 20 years old, with full crop production after 30 years

- full seed crop production every 4 to 5 years

- best seed germination occurs on a moist mineral soil

Growing sites:

- range from dry rock outcrops to bogs

- best growth on well drained moist loam soil

- usually found on cutover and burned sites

Associated species:

- largetooth aspen, white spruce, balsam fir, white birch, and red spruce on well-drained sites

- often found in pure stands

Principal damaging agents:

- hypoxylon canker, forest tent caterpillar, satin moth

Notes:

- trembling aspen comprise 2.1% of the merchantable volume in Nova Scotia

- beaver often use aspen for food and shelter

- trembling aspen is the fastest growing hardwood in Nova Scotia

- has limited use for pulpwood and fuelwood

|

Quick ID:

Trembling aspen leaves tremble in slight wind |

|

|

|

Silvics of White Ash

|

SILVICS OF WHITE ASH

(Fraxinus americana L.)

Common names:

- ash, American ash

Field identification aids:

- compound leaves, with five to nine smooth, sparsely toothed leaflets

- tree is usually straight, with a cylindrical trunk

- buds are opposite (maples are the only other species with opposite buds)

- first set of lateral buds touch the terminal bud

Average mature tree:

- 60 to 80 years

- 18 m to 21 m (60' to 70') tall

- 45 cm to 75cm (18" to 30") in diameter at breast height

Maximum life span:

- 200 years

Shade tolerance:

- medium

- can withstand moderate shade in youth, but requires more sunlight as it matures

Rooting:

- wide-spreading lateral roots will grow deep if the soil conditions permit

Windfirmness:

- windfirm

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seed or stump sprouting

- tree may begin to produce seed when 20 to 30 years old, with good crop production after 40 to 50 years

- good seed crop production almost every year

- germination is best under full sunlight on a moist, mineral soil

Growing sites:

- range from moderately drained to well-drained

- grows best on deep, moist soils

Associated species:

- beech, white birch, yellow birch, sugar maple, and hemlock on well-drained sites

Principal damaging agents:

- anthracnose, forest tent caterpillar and ash rust causes distortion of leaves and tree form (alternate hosts of this rust are marsh and cord grasses)

Notes:

- white ash comprises 0.7% of the merchantable volume in Nova Scotia

- highly prized for its strong, shock resistant wood which makes excellent tool handles and sporting goods

|

Quick ID:

White ash has bark with very deep furrows |

|

|

|

Silvics of White Birch

|

SILVICS OF WHITE BIRCH

(Betula papyrifera Marsh.)

Common names:

- paper birch, canoe birch, silver birch

Field identification aids:

- very few branches below the crown on a mature tree

- leaves are smooth and dark green above paler and slightly hairy below

Average mature tree:

- 60 to 70 years old

- 15 m to 21 m (50' to 70") tall

- 25 cm to 60 cm (10" to 24") in diameter at breast height

Maximum life span:

- 60-75 years

Shade tolerance:

- intolerant

Rooting:

- deep, spreading lateral roots

Windfirmness:

- only moderately windfirm

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seed or stump sprouting

- tree may begin to produce seed when 15 years old, with full crop production after 40 to 70 years

- generally a good seed crop is produced every year

- best seed bed is moist mineral soil

Growing sites:

- range from moderately-drained to dry sites

- best growth on well-drained, sandy loam

Associated species:

- aspen, pin cherry and grey birch on recent clearcuts and burned sites

- occasionally grows in pure stands

Principal Damaging Agents:

- nectria canker, birch leaf skeletonizer, birch sawfly, bronze birch borer

- birch dieback causes some mortality

Notes:

- white birch comprises 2.8% of the

merchantable volume in Nova Scotia

- tree can be damaged or killed if the bark is peeled off

- fast growing, short-lived tree

- used for turning, pulpwood, and fuelwood

|

Quick ID:

White birch has white bark that peels off easily |

|

|

|

Silvics of Yellow Birch

|

SILVICS OF YELLOW BIRCH

(Betula alleghaniensis Britt.)

Common names:

- curly birch, hard birch, black birch

Field identification aids:

- leaves are oval shaped with many teeth along the margins

- yellow to golden papery bark that peels off in thin strips

- bark of older tree is platy and dark

Average mature tree:

- 70 to 90 years old

- 18 m to 24 m (60' to 80') tall

- 30 cm to 60 cm (12" to 24") in diameter at breast height

Maximum life span:

- 300 years

Shade tolerance:

- medium

Rooting:

- deep, wide-spreading lateral roots

Windfirmness:

- windfirm on well drained soils

Reproduction:

- reproduces by seed or stump sprouting

- seed may begin to produce seed when 40 years old, with full production after 70 years

- good seed crop production every 1 to 2 years

- poor germination on undisturbed litter layer

- best seed germination occurs on a moist mixture of humus and mineral soil

Growing sites:

- range from well-drained to poorly-drained soils

- usually found on moderate to well-drained soils

Associated species:

- black spruce and red maple on poorly-drained sites

- sugar maple, red maple, beech, red spruce, eastern hemlock and balsam fir on well-drained sites

- seldom found in pure stands in Nova Scotia

Principal damaging agents:

- nectria canker birch leaf skeletonizer, white-marked tussock moth, bronze birch borer

- birch dieback causes some mortality

Notes:

- yellow birch comprises 5.1 % of themerchantable volume in Nova Scotia

- favorite hardwood browse of deer

- the tree often has stilted roots due to germination occurring on dead tree or stump

- one of Nova Scotia’s most valuable native birches

- commonly used for flooring, furniture, cabinet work, and veneer

|

Quick ID:

Yellow birch twigs have a wintergreen taste |

|

|

|

Module 1 - Lesson Three Quiz

| Questions: | 10 |

| Attempts allowed: | Unlimited |

| Available: | Always |

| Pass rate: | 75 % |

| Backwards navigation: | Allowed |

Lesson Four - Stand Growth and Development

Introduction

To practice good forest management, woodlot owners must be able to identify the tree species on their woodlot, understand how they grow, and how growth can be influenced.

A tree is made up of roots, a trunk or stem, and a crown. Each of these parts play an important role in the tree’s growth and development. The roots anchor the tree to the ground and absorb moisture and nutrients from the surrounding soil. The trunk supports the crown and is the link between the roots and the leaves for transporting water and nutrients. Water, nutrients, the sun’s energy, and gases from the air combine in the leaves to produce the food needed for survival.

The roots, trunk and branches are made up of the following (Figure 6):

The roots, trunk and branches are made up of the following (Figure 6):

Heartwood

An inactive wood that does not have a role in the production of food for the tree. It gives strength to the roots, trunk and branches.

Sapwood

Made up of xylem tissue, this active wood carries water and nutrients from the roots to the leaves or needles in the crown.

Cambium

The layer of cells where diameter growth occurs. It is a sheath of tissue located under the bark next to the sapwood. The inside layer closest to the center of the tree produces wood. The outside layer produces bark.

Inner bark

Consisting of tissue called phloem, it carries food made in the leaves and needles down to the branches, trunk, and roots.

Outer bark

Protects the tree from injury.

Roots, stems and branches lengthen and thicken as the tree grows. Silviculture treatments can influence the amount and rate of these changes. For example, appropriate use of early thinning can result in a stand growing to harvest size up to 20 years before an untreated stand.

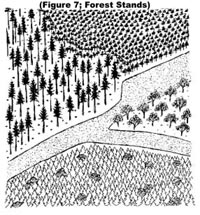

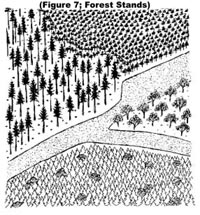

To assist in management planning and in implementing silvicultural treatments, a forest is divided into units called “stands” ( Figure 7).

Stands are groups of trees that show enough similarities in species, age, height, and density to form obvious separate units.

Stands are described using three terms: age, percentage of softwood and hardwood trees, and finally the developmental stage of the stand.

Stands are described using three terms: age, percentage of softwood and hardwood trees, and finally the developmental stage of the stand.

Even-aged stands are groups of trees with maximum age differences of 10 to 20 years. They are established after trees in an area are removed over a short period of time by fire, insect infestations and disease, wind or cutting. Uneven-aged stands are trees with at least three age classes and have a variation in heights and diameters.

Since stands may be comprised of several species in varying amounts, they are further classified by the percentage of hardwoods and softwoods:

Softwood stands contain 76% to 100% softwood trees

Mixedwood stands contain 26% to 75% softwood trees

Hardwood stands contain 25% or less softwood trees

Stands are also classified by stage of development (Figure 8). This is determined based on average height and age of the trees within the stand.

Stands are also classified by stage of development (Figure 8). This is determined based on average height and age of the trees within the stand.

A forest is a complex and dynamic community in which trees grow and develop from seedlings through maturity. A number of physical and biological factors continually influence the growth and development of forests and must be understood before you can begin to practice good forestry.

Although the effect of these factors may be more easily understood when discussed individually (e.g., soils), it is more complicated when all factors are considered together as an ecosystem. Nevertheless, an appreciation of their existence and effect on the forest will help you understand the reasons behind good silvicultural practices.

The following is a list of the major physical and biological factors which affect trees as they grow from the seedling stage maturity:

Physical Factors

Climate

- temperature (average and extreme)

- rainfall (average and extreme)

- wind (average and extreme)

- severity and regularity of damaging storms (for example, hurricanes and sleet storms)

Soils

- structure (loose or compact)

- texture (clay, sand, or gravel)

- fertility

- depth

- drainage

- ground vegetation

Location

- altitude

- slope (%)

- orientation or direction of slope

- exposure

Biological Factors

Silvics of each tree

- reproductive capacity

- shade tolerance

- rooting capacity

- growth potential

- resistance or susceptibility to insects, diseases and windthrow

Stand features

- density

- species composition and distribution

Damaging Agents

- disease

- insects

- mammals

- mechanical

When managing a woodlot, it is important to know which biological factors can be changed and which physical factors cannot.

For example, since the soil cannot be easily changed, the species you plant and/or regeneration you try to encourage must be compatible with the soil type. You could try a number of silvicultural treatments and still not achieve maximum growth if the trees are not suited to the soil.

A Forest Ecosystem Classification guide was published by the Nova Forest Alliance (Keys et al. 2003 )for use in central Nova Scotia. In this guide forest ecosystems are grouped based on tree species, ground vegetation, soil type and other features of the site. This guide allows woodlot owners and forestry professionals to group similar sites together. Once similar sites are identified owners can better address hazards and operational limitations associated with these ecosystems. This classification makes management outcomes more predictable and thus sustainable.

Experience is also very important. Woodlot owners who observe local conditions can provide valuable practical knowledge in addition to general silviculture principles.

Site Capability

The ability of a forest to grow is related directly to physical site factors. Favourable physical factors create better land capability rating and a better response to silvicultural treatments. Land capability is determined by comparing the total age of a healthy dominant tree to its height. Better site qualities produce taller trees at any given age. For example, a 70 year old tree which is 23 metres (75') tall is probably growing on a better site than the same 70 year old tree that is only 16 metres (52') tall.

Sites lower than capability 4 (capable of 4 m3/ha/yr) (0.7 cds/ac/yr) are not generally worth spending a lot of time and money on. The potential of these sites to respond to silvicultural treatments is very low.

Land capabilities are grouped by number. In Nova Scotia, the best is land capability class is 13. With management, this class is capable of producing 13 cubic metres per hectare per year (m3/ha/yr) (2.3 cords/acre/year). The worst is land capability 1, capable of producing only 1 m3/ha/yr (0.2 cds/ac/yr) even under management. Examples of the expected growth rates for different site classes are listed below:

1) A stand growing on a site class 7 takes an average of 7 years to reach a height of 3m (10')

2) A stand growing on a site class 5 takes an average of 10 years to reach a height of 3m (10')

3) A stand growing on a site class 4 takes an average of 15 years to reach a height of 3m (10')

Stand Density and Stocking

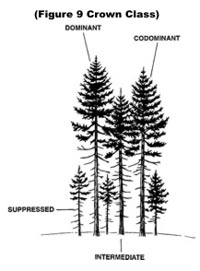

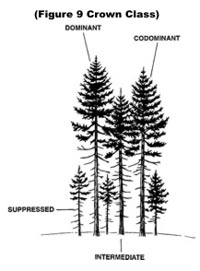

In growing from seedling to maturity, trees constantly compete for sunlight, moisture, food, and space. The healthier, vigorous trees on better sites soon overtop their neighbours and become dominant and codominant members of the stand. The remaining trees develop into intermediate or suppressed positions within the stand (Figure 9).

Genetically superior trees and more vigorous species have an advantage and often quickly establish superior height positions in the forest canopy. Inferior trees are at a distinct disadvantage.

Genetically superior trees and more vigorous species have an advantage and often quickly establish superior height positions in the forest canopy. Inferior trees are at a distinct disadvantage.

Density is usually expressed as number of trees per unit area (hectare or acre). It reflects the degree of crowding of trees in a stand. Stocking is a relative term usually expressed as a percentage, which refers to amount of growing space used by trees. An area with enough trees to use all the available growing space is considered 100% stocked. An area where only half of the available growing space is occupied by trees is 50% stocked.

During stand establishment, thousands of trees may germinate, but that number will decrease through natural mortality as the stand ages. The higher the initial density, the greater the competition, resulting in many trees being eliminated from the stand. At maturity, the available sunlight, moisture, nutrients, and space will be used by fewer, larger trees.

When a tree dies, it creates an opening in the forest canopy. As it decays, nutrients stored in the foliage and wood fibre are released into the soil. In a young stand, the opening is filled by the branches of the surrounding trees. In a mature stand the open space provides an area where regeneration can establish.

Throughout its life, a tree must have enough space to spread its crown and roots in proportion to its size to reach maximum growth. If there are too many trees competing for the same space and the trees will be smaller. If there are not enough trees, the existing trees will develop large limbs and extensive crowns. Much of the growing space will be utilized by undesirable, non-commercial species. This also results in an overall reduction of stand growth.

A species’ ability to survive in a dense stand depends on its height growth and to a greater extent, its tolerance of shade. Tolerant trees are able to survive and grow under various shade conditions. Intolerant trees cannot persist for very long in shade. It is important to consider this when planning silviculture operations. If your objective is to produce a stand of tolerant trees, a shelterwood or selection harvest method should be used rather than a clearcut. Module 2 provides more information on harvesting systems.

Species Composition

Species composition will vary throughout the life of a stand, depending on stand density and age. As stands get older intolerant species generally die and are replaced by more tolerant species which are better able to compete and grow in the reduced sunlight.

Species composition will vary throughout the life of a stand, depending on stand density and age. As stands get older intolerant species generally die and are replaced by more tolerant species which are better able to compete and grow in the reduced sunlight.

Growth

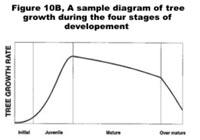

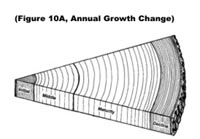

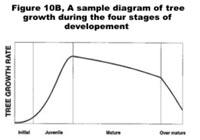

As trees age they go through three major phases of development - immaturity, maturity, and decline. Through each phase, changes occur in the rate of height, diameter and volume growth; stand density, stocking and development, and species composition (Figure 10 A).

Height Growth

Height Growth

Trees grow in height from the terminal bud, if the terminal leader is not damaged. The greatest rate of height growth happens during the immature stage (Figure 10 B). Although a tree will continue to grow in total height, the rate will decrease as the tree matures. The final height that a healthy, vigorous tree reaches depends on the site capability. The better the site the taller a tree will be at a given age.

Diameter Growth

Diameter Growth

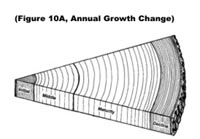

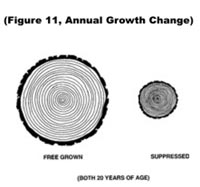

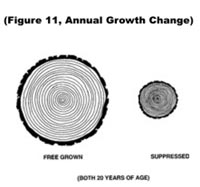

Each year, a tree produces an annual ring made up of a light and dark band of wood. The light band occurs during the spring and early summer. The dark bands are produced in late summer and early fall. These rings occur in the trunk, roots, rootlets, branches and twigs of all trees (Figure 11). Annual rings are very important in forestry since they reflect the history of a tree or stand.

A tree’s age can be determined by counting the rings. The rate of diameter growth throughout a tree’s life can be seen in the various widths of the rings. When a tree is suppressed, the rings are narrow and when the tree is growing well and free of competition, the rings are wide.

The rate of diameter growth is directly related to stocking. Generally, the greater the stocking the slower the rate of diameter growth. Diameter growth is reduced by suppression from the side and from above.

If a tree is released from competition, the rate of diameter growth will normally increase. Constant competition throughout the tree’s life will result in a smaller diameter tree at maturity, regardless of the site capability.

If a tree is suppressed on one side only, the diameter growth will normally be less on the suppressed side. For example, trees along the edge of a field will usually have more diameter growth on the side facing the field, while the forested side will have less.

Because of the competition in a stand, trees of the same age may exhibit a wide variation in diameters. A tree with a large diameter could be the same age or younger than a neighbouring tree with a smaller diameter.

Volume Growth

Volume Growth

The rate of volume growth, like height and diameter growth, is generally greater during the early stages of a tree’s development. Since volume growth is dependent upon both height and diameter growth, factors that influence height and diameter will also affect the volume.

Stand volume is directly related to stocking. That is, stand volume will increase as stocking increases (Figure 12) because the site is being more fully utilized.

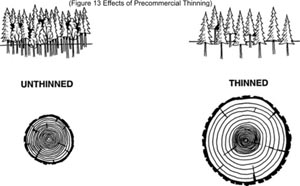

Manipulation of Stands by Thinning

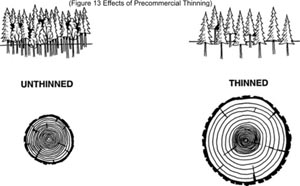

As mentioned earlier, growth and development of a stand is significantly affected by competition with other trees. In some cases, competition is beneficial; such as in hardwood or white spruce stands where density will minimize excessive limbiness. In dense stands, competition from neighbouring trees slows the growth and development of the stand (Figure 13).

To enhance the growth and development of your woodlot, competition must be adjusted through spacing treatments. Precommercial thinnings are treatments used to achieve desired spacing between trees. With the exception of planting, most silvicultural approaches to stand management involve altering the existing spacing.

Reducing competition by thinning allows the remaining trees to grow to the site’s capability. Thus, more merchantable wood will be produced sooner. The extra space will also allow for the growth of larger trees that will have a higher value, such as sawlogs.

Reducing competition by thinning allows the remaining trees to grow to the site’s capability. Thus, more merchantable wood will be produced sooner. The extra space will also allow for the growth of larger trees that will have a higher value, such as sawlogs.

Thinning treatments remove undesirable trees and free the best ones from competition. Undesirable trees are those that are diseased and/or damaged, unwanted species, and ones that are crowding better quality trees. Which trees are undesirable will vary with each situation. Therefore, it is important to always know what type of tree species or forest product you want to encourage on your woodlot. Thinning is covered in more detail in Module 3.

Module 1 - Lesson Four Quiz

| Questions: | 10 |

| Attempts allowed: | Unlimited |

| Available: | Always |

| Pass rate: | 75 % |

| Backwards navigation: | Allowed |

For Further Reading

Atlantic Provinces Economic Council. March 2000. The Economic Impact of the Forest Industry on the Nova Scotia Economy.

Atlantic Provinces Economic Council. January 2003. The Forest Industry in the Nova Scotia Economy (2002 Update).

Burns, R.M. and B.H. Honkala. 1990. Silvics of North America. Vol. 1 Conifers. Agriculture Handbook #654. USDA Forest Service.

Burns, R.M. and B.H. Honkala. 1990. Silvics of North America. Vol. 2 Hardwoods. Agriculture Handbook #654. USDA Forest Service.

Canadian Institute of Forestry, 2001. Nova Scotia News - CIF Celebrates National Forest Week.

http://www.cif-ifc.org/

Dansereau, J.P., and P. deMarsh, 2003. A portrait of Canadian Woodlot owners in 2003. Forestry Chronicle. 79(4): 774-779

Farr, K. 2003. The Forests of Canada. Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Markham ON. Natural Resources Canada, Ottawa.

Farrar, J. L. 1995. Trees in Canada. Fitzhenry and Whiteside. Ottawa; Canadian Forest Service.

Forestry Canada. 1992. Silvicultural terms in Canada. Ottawa, ON.

Johnson, R.S. 1986. Forest of Nova Scotia a History. Department of Lands and Forests. Four East Publications. Halifax, NS.

Keys, K.P. Neily, E. Quigley and B. Stewart. 2003. Forest Ecosystem Classification of Nova Scotia’s Model Forest. Nova Forest Alliance. Stewiacke, NS.

Natural Resources Canada. 2004. The State of Canada’s Forests 2003-2004. Ottawa, ON.

Nova Forest Alliance. Forest Ecosystem Classification of Nova Scotia’s Model Forest. Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources

Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources. 1997. Toward Sustainable Forestry: A Position Paper. Working Paper 1997-01.

Natural Resource Education Centre. Forest Sustainablity - A Grade 10 Science Project. Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources.

Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources. 2000a. Sustaining Our Wood Supply Through Increased Silviculture. Information Leaflet FOR-3.

Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources. 2000b. Ten Year Periodic Annual Increment for Nova Scotia Permanent Forest Inventory Plots 1980-85 to 1990-95. Report FOR 2000-2.

Robertson, R.G., R.W. Young and J.C. Lees. 1991. Hardwood Thinning Manual. Department of Lands and Forests.

Robertson, R.G., R.W. Young. 1990. Merchantable Thinning Manual - Softwoods. Department of Lands and Forests.

Saunders, G.L. 1995. Trees Of Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources.

Townsend, P. 2004. Nova Scotia Forest Inventory, Based on Permanent Sample Plots Measured between 1999 and 2003. Report FOR2004-03. Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources.

Wellstead A., P.D. Brown. 1995. The 1993 Nova Scotia Woodlot Owner Survey Executive Summary. Department of Natural Resources.

Wilson, B.F. 1970. The Growing Tree. University of Massachusetts Press

Glossary of Key Terms - Module 1

ACADIAN FOREST: The Acadian Forest is one of 12 forest regions in Canada. It is characterized by red spruce, balsam fir, maple and yellow birch.

ARTIFICIAL REGENERATION: Establishing a forest by direct seeding and/or planting.

BASAL AREA: The area in square meters (square feet) of the cross section of the trunk of a tree at breast height. Most commonly used as an indicator of stand density and is expressed as square metres/hectare (square feet/acre).

BIODIVERSITY: The variety of life in all its forms, levels and combinations. Includes ecosystem diversity, species diversity and genetic diversity.

BIOLOGICAL: Characteristics of living organisms which influence their growth and health.

BLOWDOWN: Trees uprooted by high winds, commonly called windthrow.

BREAST HEIGHT: The standard height, a distance 1.3 meters (4.5') above ground level, where the diameter of a standing tree is measured.

BUDS: Undeveloped shoot, leaf, or flower enclosed in protective scales. Terminal buds are located at the end of a twig. Lateral buds are located below the terminal bud and along the sides of the twig.

CANOPY: Cover of branches and foliage formed by tree crowns

CLEARCUT: The removal of all or most merchantable trees from an area.

CODOMINANT: Trees with crowns in the general level of the canopy which receive full light from above, but comparatively little from the side. Trees have medium-sized crowns.

CONES: The fruiting bodies of coniferous trees which produce the seed.

CONIFEROUS TREES: Commonly called softwood or evergreen, trees that have cones and keep their needles throughout the winter, except for tamarack.

DECIDUOUS: Commonly referred to as hardwoods or broad leaf trees, in most cases, they lose their leaves in the fall.

DENSITY (STAND): A measurement of the stand in terms of square metres of basal area, number of trees, or volume per hectare. It reflects the degree of crowding of stems within the stand. Expressed as basal area, it is a measurement of the portion of an area occupied by trees at breast height. Expressed as percentage of crown closure, it is an estimate of the extent the site is occupied.

DISTRIBUTION: The arrangement of stand characteristics such as height, age, diameter and species.

DOMINANT: Trees with crowns extending above the general level of the canopy and receiving full light from above and partial light from the sides. They are larger than the average trees of the stand with well developed crowns.

DUFF: The shallow layer of organic soil and litter of the forest floor which lies over the general mineral soil.

ECOSYSTEM: An ecosystem consists of a dynamic set of living organisms (plants, animals and microorganisms) all interacting among themselves and with the environment in which they live (soil, climate, water and light).

EVEN-AGED STAND: A stand of trees with maximum age differences of 10-20 years and of approximately the same height.

FOREST: A group or community of trees and plants divided up into forest stands.

FOREST ECOLOGY: The relationship between forest organisms (plants and animals) and their environment.

GENETIC: The inherent physiology and development of living organisms as determined by the genes.

GERMINATION: The growth process of a mature seed, characterized by the emergence of a stem and root.

GROUND VEGETATION: Non-woody vegetation under 1.2 metres (4') in heigh.

HIGH-GRADING: Harvesting the biggest, best and most profitable trees and leaving the less desirable trees. May result in the growth of a poor quality stand. Also called selective harvesting.

HUMUS: Black or brown material found in soil, formed by partial decomposition of plant or animal material (organic matter).

IMMATURE STAND: A stand of young trees past the regeneration stage usually showing good health and vigor.

INTERMEDIATE: Trees with crowns extending into canopy formed by dominant and codominant trees which receive a little light from above, but not from the sides.

INTOLERANT: The inability of a tree to maintain health and vigor under shade. Intolerant trees require full sunlight to maintain vigorous growth. Referred to as pioneer species.

LATERAL ROOTS: Relatively shallow roots which spread outward from the tree parallel to the ground.

LAYERING: A method of reproduction in which living lower branches come in contact with moist ground or are covered with litter and produce roots. These branches eventually grow into trees separate from the parent tree. It is a common reproduction method of black spruce.

LEADER: the main shoot of a tree. Will form the trunk as the tree grows

LOAM: A loose soil composed of clay, sand, and organic matter, often highly fertile.

LITTER: The top layer of debris (fallen leaves, needles, flowers, bark...) on the forest floor.

MATURE STAND: A trees is considered mature when height, diameter and volume growth level off. Different species mature at different ages.

MINERAL SOIL: Soil containing a high percentage of inorganic material such as rock, sand, clay, and silt.

NATURAL REGENERATION: Renewal of trees by natural seeding, sprouting, suckering, or layering.

ORGANIC SOIL: Soil containing a high percentage of dead or decaying plant matter (also called organic material) from fallen material such as needles and leaves, slash and blowdown.

PIONEER SPECIES: The first species to grow following a natural disturbance like fire or a harvest. These species are shade intolerant and normally short-lived. Common pioneer tree species in Nova Scotia are pin cherry, trembling aspen and red maple.

PRECOMMERCIAL THINNING: A spacing treatment carried out in young naturally regenerated stands which removes competition and concentrates growth on desired trees.

PURE STAND: A stand with at least 80% of the trees in the main canopy are of a single species.

REGENERATION: The reforestation or reproduction of the forest by either natural seeding or artificial means. Generally refers to established seedlings.

RESIDUAL TREES: Scattered, standing trees left by harvesting in an area which has undergone extensive harvesting.

ROTATION: The period of years to establish and grow timber crops to a specified condition of maturity from regeneration to final harvest.

SELECTION HARVEST: The removal of the trees of all sizes or a range of sizes, either as single, scattered individuals or in small groups as relatively short intervals repeated indefinitely. The continuous establishment of new trees and uneven-aged stands is encouraged.

SELECTIVE HARVESTING: Harvesting the biggest, best and most profitable trees and leaving the less desirable trees. Also called high grading.

SHADE TOLERANCE: Shade tolerance refers to a tree’s ability to survive and grow in shaded conditions

SHELTERWOOD CUT: The removal of the mature timber in a series of cuttings which extend over a relatively short portion of the rotation. The establishment of Even-aged reproduction is encouraged under the partial shade of seed trees.

SITE CAPABILITY: An expression of a particular area’s ability to support forest growth. Expressed as volume/area/year. The better capability, the greater the rate of height and growth volume.

SPECIES: A category of individuals thought of as a group because of common qualities and characteristics.

SPROUTING: A form of natural regeneration that occurs when the main stem is removed. Dormant buds in the stump begin to grow into new shoots (for example red maple).

STAND: A group of trees, with similarities in species composition, height/diameter distribution, and age composition.

STAND STRUCTURE: The distribution of tree species and their age, height, species composition, diameter, and density of a specific area.

STOCKING: A relative term usually expressed as a percentage which refers to the number of trees that occur in a given area. An area that supports sufficient trees to optimally use all the available growing space is said to be 100% stocked. An area where only half of the available growing space is occupied by trees is said to be 50% stocked.

STUMPAGE: The price paid to the owner of standing timber, before the trees are harvested.

SUCKERING: Sprouting up from the roots, usually after a disturbance. Occurs in species with shallow rooted hardwoods such as red maples, beech and trembling aspen.

SUPPRESSED: Trees below general level of the canopy receiving no light either from the sides or above.

TAP ROOT: A deep root growing down into the ground which helps anchor the tree and maintain a water supply in dry soils.

TOLERANCE / TOLERANT: The ability of a tree to regenerate and maintain health and vigor under shaded conditions. Very tolerant tree species can grow in dense shade.

UNEVEN-AGED STAND: A stand trees with considerable age differences representing at least three age classes. Uneven-aged stands contain large, older trees as well as immature trees.

WINDTHROW: Tree(s) uprooted by wind, commonly called blowdown.

Downloads

As the Home Study modules become available copies will be made available for download. At this time only the Introduction - Getting More from your Woodlot, Module 2 and 9 are available in French.

|

All modules are currently available in English and some in French |

Adobe Acrobat

Acrobate D'Adobe |

|

Principles of Forest Stewardship |

Download |

|