Lesson Three - Habitats and Species of Special Conservation Concern

LESSON THREE: HABITATS AND SPECIES OF SPECIAL CONSERVATION CONCERN

Some species and habitats are more vulnerable than others or occur in low numbers. Some species have the misfortune of having their habitats lost or degraded by the building of urban habitats for humans. Humans have also introduced contaminants that pollute or poison. Humans have over exploited some species or introduced invasive species that have displaced native species.

Some generalist species (American crow) adapt readily to man-made environments, while other more specialized species (ram’s head lady slipper) do not.

Many endangered, threatened and vulnerable species occur in oceans (north Atlantic right whale) or along coastlines (piping plover) so of course are not directly influenced by woodlot activities. Many species thrive and are common in woodlots (snowshoe hare) and are not a conservation concern. However, some species are rare or have specialized habitats and require special attention.

Lesson Three first describes sensitive and important woodlot habitats that require special care when doing forest management. Lesson Three next describes woodland species that for various reasons have low population numbers and again require special care. Some of these species are so close to nonviable population sizes that they have special protection by provincial and federal laws

TAKING CARE

Habitats Sensitive to Forestry

Woodlot habitats are important to wildlife, but without care, sensitive habitats on woodlots can be destroyed or degraded by forestry activities.

RIPARIAN AND STREAM ECOSYSTEMS

Wildlife is proportionally most numerous along watercourses. Within the watercourses and the special habitat alongside, there are a multitude of values for wildlife and water quality that need special attention. Riparian Zones are lands adjacent to streams, rivers, lakes, and other water bodies. Riparian zones have rich, moist soils and often unique and diverse vegetation. Periodic flooding and deposition of alluvial sediments and a flow of nutrients from upland areas builds rich productivity. Riparian zones are linear and are natural wildlife travel corridors. Moving away from the watercourse, there is a series of natural edges from the water to the upland. The riparian zone shades the watercourse and is a supply of woody debris and logs into the watercourse. Branches and trees enter the stream and provide substrate and in-stream habitat for invertebrates and fish. Water falling over large logs dig out pool habitat, creating essential deep-water areas for brook trout. Most nutrients in a watercourse come from the riparian zone. Remember the food chain in Lesson One where food energy started with photosynthesis. Leaf litter and other detritus that enter the watercourse are the start of in-stream food chains. Energy flows through bacteria feeding on decaying plants, to stonefly larvae, to trout. Yes, if the imagination is stretched, fish come from trees.

Trout and salmon, particularly sensitive among fish, require clean water streams with sediment-free bottoms. The riparian zone moderates flooding and buffers the movement of sediments into the stream.

In Lesson One we learned that wildlife are adapted to “just the right place to live.” Plants along a riparian zone are adapted to an occasional periodic flooding, but the reward for this adaptation allows them to live in a niche with excellent moisture and fertility. Some are adapted to living closer to the stream than others. The animals that use the riparian zone also show a gradient of dependence on water. The fish and dragonfly nymphs are totally dependant to life in water. The dragonfly will eventually emerge and feed over the water’s edge and through the riparian zone. Many amphibians lay eggs in water but spend the majority of their lives within the terrestrial riparian zone. Wood turtles hibernate on the bottom of streams, lay eggs in sand and gravel stream banks, and feed throughout the riparian zone. Raccoons often forage along stream banks, but are equally comfortable living in town and eating garbage. Most woodland terrestrial vertebrates visit water to drink or to find food and shelter in the forest alongside a brook. Watercourses and riparian zones are special places.

Later in Lesson Four students will learn about provincial regulations that protect watercourses.

VERNAL POOLS

Vernal pools are depressions within a woodlot that become water filled in the spring. Pond size might vary from 10 m2 to 1000 m2. How long water remains in these pools is highly variable. Water in some pools might remain only a few weeks, while others are almost permanent, perhaps only drying out in years of drought. They are particularly important for certain amphibians, reptiles, and invertebrates. A very important feature of vernal pools and their inhabitants is the absence of adult predatory fish. Spring peepers, wood frogs, and yellow and blue spotted salamanders breed in these pools. These pools are frequently visited by typical wetland species such as mink, great blue heron, and wood turtles, where they find rich feeding opportunities. Numerous upland birds and mammals go to these pools to drink, bathe, and feed.

Equally important is the forested habitat adjacent to vernal pools since it is here that the amphibians spend the terrestrial portions of their life cycle.

Although not required by law, “Special Management Zones” should be maintained around vernal pools. The surrounding forest is critical to maintaining water quality, shade, and litter for the pool.

Woodlot owners should examine their property in spring to identify these sites.

BEAVER-INFLUENCED ECOSYSTEMS

Woodlot owners either love beaver or hate beaver. The experience of flooded roads or land is a cause of conflict between woodlot owners and wildlife. Beaver ponds are a temporary wetland and the wetland cycles through successional stages. For the first seven years after the establishment of a new beaver flowage, there is high productivity. Nutrients are released from newly flooded soils. As organic material accumulates on the pond bottom, productivity declines. Beaver move to a new site after their food supply is depleted. The beaver dam falls into disrepair and a there is a new period of great productivity as a meadow develops. Over time trees will again grow on the meadow and beaver return to begin the cycle anew.

Each stage of the cycle provides habitat and a changing assemblage of wildlife.

Installing “beaver puzzles” is a solution that prevents road flooding and accommodates the tremendous wetland habitats created by beavers. To install a beaver puzzle, you put a drain through the dam to hold the water at an acceptable and stable level. The siphon device deadens the sound of the escaping water. The beaver cannot figure out the location of the leak and therefore cannot repair it.

Carl shows a picture of some DNR summer students installing a Clemson Leveler. This was a successful experiment with Ducks Unlimited and a woodlot owner that had a valuable wetland but a flooded road problem.

WOODLAND SEEPS AND SPRINGS

Probably many woodlots have wet sites that remain unfrozen in the winter. They are not identified as a stream since there is no streambed. At these wet spots, groundwater flows to the surface and saturates the soil. Small streams might start, but may return underground. Common sense dictates that you avoid using logging equipment at these sites.

Plants such as water pennywort, jewelweed, or sensitive fern often dominate these sites. These seeps are a source of water for wildlife during winter months. The sites provide early green vegetation, earthworms, and insects to sustain early migrants such as robins and woodcock.

Extensive logging or the operation of heavy equipment will destroy or degrade these sites.

DEER WINTERING AREAS

Dan Barr knows that his woodlot is used in the winter by deer. In winter he sees deer and finds their beds in the snow. In spring he finds large numbers of deer pellet piles throughout his softwood stands and on trails along the brooks. Dan’s woodlot is on the south slope of the Cobequid Hills. As snowfall deepens each year, deer migrate off the elevated Cobequid Hills into conifer forests at lower elevations. One winter after Dan had done a harvest, he counted 60 deer feeding on the lichens on branches over his cut area.

The biggest winter deer concentrations in Nova Scotia are adjacent to summer ranges that occur over higher elevations, such as north of the Bras d’Or Lakes or the Cobequid Hills where deer must move in winter to south facing slopes. Deer must move off the high ground in winter because snow melts less and accumulates. Deer winter concentrations in western Nova Scotia, with less high topography, are more local and in smaller groups. Deer also often move to coastal locations in winter and are known to eat seaweed.

Winters in Nova Scotia are variable. In winters of very deep snow, deer must seek the shelter of softwood cover. If the mobility of deer is very restricted, the deer have the ability, but not an indefinite ability, to remain inactive and survive on body fat.

Extensive forest harvest that removes limited softwood cover opportunity will greatly reduce deer numbers, particularly in areas where there are large winter concentrations of deer. In Cape Breton when spruce budworm drastically removed softwood cover, deer numbers crashed.

For a woodlot owner with a known “deer yard,” it is important of course to maintain softwood stands suitable for winter cover.

Maintaining deer cover benefits other wildlife species as well. The softwood habitat is important for fisher. Several birds—including merlin, black-backed woodpecker, and pine grosbeak—also occur in this mature softwood forest.

NEST SITES FOR HERONS AND WOODLAND RAPTORS

Great blue herons nest in colonies and build stick nests in treetops. For the most part in Nova Scotia great blue herons nest on isolated islands, but colonies sometimes are found in forested inland locations. They often travel considerable distances from their nesting sites to feeding areas. At one Nova Scotia island, great blue herons are known to make 16 km round trips from the young in nests on the island to coastal wetlands on the mainland where they catch food.

blue herons nest on isolated islands, but colonies sometimes are found in forested inland locations. They often travel considerable distances from their nesting sites to feeding areas. At one Nova Scotia island, great blue herons are known to make 16 km round trips from the young in nests on the island to coastal wetlands on the mainland where they catch food.

Great blue herons are easily disturbed by human activity. Adults will flush if intruders approach within 100 to 200 metres. Herons, like raptors, are more sensitive during the courtship and nest-building stage of nesting. Older nestlings might leap from nests if disturbed before they are able to fly.

Unlike herons, nests of hawks, eagles, and owls, have nests widely dispersed. Different species have different preference for where they choose to nest. Some (broad-winged and goshawk) prefer unbroken tracts of forest and others (kestrel and red-tailed hawk) prefer forest interspersed with large openings. The saw-whet owl nests in tree cavities. Several other birds of prey use stick nests. For the most part, raptor species and forest management are not in conflict. Woodlot owners should be on the lookout for raptor nests. Owls are often incubating in March and many hawks in April and May.

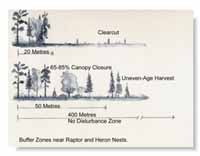

When you locate a raptor nest or heron colony, establish a protective management zones around the nest. Exact recommendations for these zones vary, but all are meant to achieve the same purpose. Create an inner zone closest to the nest or colony with restricted tree harvest and no disturbance during nesting times. The width of the buffer zone will vary depending on whether there is a planned surrounding clearcut or a selective cut. If a clearcut is occurring next to a nest, New England literature recommends that you leave a 20-metre uncut buffer. Some species, such as herons or goshawks, are more sensitive to disturbance than others. Talk to regional biologists at Natural Resources for specific advice. Establish an outer zone that allows usual forest activity, but with no high disturbance activities such as harvest or road building during the nesting period.

When you locate a raptor nest or heron colony, establish a protective management zones around the nest. Exact recommendations for these zones vary, but all are meant to achieve the same purpose. Create an inner zone closest to the nest or colony with restricted tree harvest and no disturbance during nesting times. The width of the buffer zone will vary depending on whether there is a planned surrounding clearcut or a selective cut. If a clearcut is occurring next to a nest, New England literature recommends that you leave a 20-metre uncut buffer. Some species, such as herons or goshawks, are more sensitive to disturbance than others. Talk to regional biologists at Natural Resources for specific advice. Establish an outer zone that allows usual forest activity, but with no high disturbance activities such as harvest or road building during the nesting period.

OLD GROWTH FOREST

Definitions for old growth forest are confusing. If a forest is allowed to develop through hundreds of years, the tree species that are long-lived and shade tolerant will eventually dominate. These trees are 100 to 200 years old, and sometimes over 300 years.

The age of an old growth forest is much older than an economically mature forest, ready to be cut and rotated for the next crop.

Old growth forests have many features that contribute to wildlife biodiversity. These features are vertical diversity, lots of cavity trees and downed coarse woody debris, and habitat for forest interior species.

The Department of Natural Resources has information on maximum ages for several NS tree species. (Bruce Stewart).

| Species |

Literature

|

Collected by NS

Source DNR From Old Growth Stands |

|

|

||

| Red Spruce |

400

|

294

|

| Hemlock |

988

|

333

|

| White Pine |

450

|

288

|

| Black Spruce |

250

|

203

|

| Balsam Fir |

200

|

173

|

| Sugar Maple |

400

|

254

|

| Yellow Birch |

300

|

313

|

| Red Oak |

300

|

159

|

| Beech |

366+

|

132

|

|

|

||

In providing old-growth habitat, as Carl mentioned in Lesson Two, there is a challenge to accommodate the interests of both wildlife managers and the forest industry. Society requires forest products and the family incomes from the forest industry; however, forests should remain healthy and maintain biodiversity. There are many good people in forestry who also want healthy and biodiverse forests.

Woodlot owners should consider preserving stands that now exhibit old growth forest characteristics or to look at the best remaining opportunities to restore over time a portion of a woodlot as old growth.

How to recognize old growth:

- old trees (shade-tolerant species)

- large diameter trees (40–60 cm)

- large dead wood (snags and fallen trees)

- multiple understory tree layers

- canopy openings

- primal conditions (no logging evidence)

There is a species of tiny stalked “stubble” lichen that resembles whiskers. Known as frosted glass-whiskers, this lichen is listed as Special Concern by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). It occurs only in old growth hardwood forests in Cape Breton. The entire present known physical area of coverage for this lichen is one square metre.

Woodlot owners should also begin the conversion from even-aged stand management to uneven-aged stand management. This is not a quick process and will require children and grandchildren to complete. This converted forest would have old growth forest characteristics, but it is not necessarily meant as a hands-off forest. Woodlot owners can choose to harvest quality trees, yet still retain old-growth characteristics.

During this class discussion on old growth, Dan Barr thinks of his son, Michael, who now works on the oil rigs. He thinks Michael will carry on his interest in the woodlot. When Michael is home, he spends a lot of time at the camp and has installed a solar electrical system. Mike also helps Dan with Christmas tree shearing.

The children of many of his neighbours now live in cities. Dan worries that they are becoming less connected to the land. He also worries that long term interest by dedicated woodlot owners will be a problem.

RARE PLANT AND ANIMAL SITES

RARE PLANT AND ANIMAL SITES

Plants or animals in Nova Scotia are often rare because they are at the southern or northern limit of their preferred range. Some plants arrived in Nova Scotia when glaciers were retreating thousands of years ago. As climate warmed a few of these Alpine species still persisted in small numbers by growing in hostile locations such as cliff faces. Nova Scotia was also once a much warmer place. Blanding turtles once occurred widely, but now are restricted to central western Nova Scotia where summer temperatures are warm enough to allow the eggs to hatch.

Some species, such as hepatica, are rare because of agriculture and urban development. The NS Department of Natural Resources maps sites of rare species when they are discovered. During environmental assessments, developers are required to check this mapping. Many rare species are associated with wetlands and riparian zones, and their occurrences here emphases that these areas require protection or only low impact activities.

Rock faces, natural caves within gypsum formations, and old quarries might have unique wildlife use. Three species of bats hibernate in Nova Scotia. To hibernate they require access into old mines or natural caves. These mines and caves have the milder temperatures and high humidity that allow the bats to hibernate successfully. Woodlot owners should regard bats as friends since they consume huge quantities of moths. An old quarry might have snake hibernacula. Rare plants such as showy lady slipper might be found near gypsum areas.

Nova Scotia Significant Species and Habitat ('Sighab') Database

The DNR Wildlife Division has an online mapping database with location information for significant wildlife species and habitat in Nova Scotia. For more information on the Sighab database and to view the database online visit the following NS DNR Wildlife Division website: http://www.gov.ns.ca/natr/wildlife/Thp/disclaim.htm

The following nine types of habitat polygons are mapped:

- species at risk as designated by the NS Endangered Species Act

- other species of concern with red or yellow status

- deer wintering areas

- moose wintering areas

- important migratory bird habitat

- freshwater habitats

- rare plant sites

- ecological sites

- other significant habitats

Woodlot owners can view online maps and determine if any significant habitat polygons occur on their woodlot. Regional biologists and the Wildlife Division keep a database with details about each polygon. For example, if a site was visited there might be data on the number of rare plants counted or perhaps the number of young in an eagle’s nest. Some of this data is sensitive and only released on a need-to-know basis. If a woodlot owner does see a polygon on their property, then they can contact the regional biologist for further information. The biologists are more than glad to have contact with owners of significant habitats.

The Significant Habitat Mapping is far from complete. Woodlot owners are encouraged to report sightings of rare species to regional biologists.

Species at Risk

There is a wealth of information on Species at Risk presently on the Internet. The Department of Natural Resources Biodiversity web page at

http://www.gov.ns.ca/natr/wildlife/biodiv/biodiversity_datainfo.htm has some very useful links.

The Nova Scotia Endangered Species Act

In 1999 Nova Scotia enacted the Nova Scotia Endangered Species Act. Through this act, those Nova Scotia species thought most at risk are designated and recovery teams are formed to write recovery plans. For example, there is a recovery plan for Blanding’s turtles written by several persons knowledgeable about this species.

Species listed up to the year 2006 in Nova Scotia are:

ENDANGERED

Blanding’s Turtle¹ (Western Nova Scotia)

Roseate Tern¹

Piping Plover¹

Harlequin Duck¹

Pink Coreopsis¹ (Coastal Plain Flora)

Thread-Leaved Sundew¹ (Coastal Plain Flora)

Eastern Mountain Avens¹ (Brier I/Digby Neck)

American Marten*

Water Pennywort (Coastal Plain Flora)

Plymouth Gentian¹ (Coastal Plain Flora)

Atlantic Whitefish¹ (Petite Riviere Watershed)

Canada Lynx (Cape Breton)*

Mainland Moose*

Boreal Felt Lichen¹*

THREATENED

Peregrine Falcon¹

Golden-Crest¹ (Coastal Plain Flora)

Redroot¹ (Coastal Plain Flora)

Eastern Ribbon Snake¹ (Western Nova Scotia)

Tubercled Spikerush¹ (Coastal Plain Flora)

Yellow Lamp Mussel¹ (Cape Breton)

VULNERABLE

Sweet Pepperbush¹ (Coastal Plain Flora)

Wood Turtle¹*

New Jersey Rush¹ (Coastal Plain Flora)

Long’s Bulrush (Coastal Plain Flora)

Bicknell’s Thrush¹*

Prototype Quillwort¹ (Lakes)

Eastern Lilaeopsis¹ (Estuaries)

Eastern White Cedar*

¹ Indicates the species is listed also by federal legislation.

* Species marked ‘*’ are those most likely affected or have dependence on forest environments.

The other species are unlikely to be encountered on a woodlot. Coastal Plain Flora is usually found on lakeshores such as Ponhook or Molega Lakes in western Nova Scotia. As the water level of these lakes drop in summer exposing the shoreline, these plants take this short opportunity to grow and blossom without the competition from other plants.

The following is information on the forest-related species designated by the Nova Scotia Endangered Species Act.

American Marten

The Cape Breton population of Marten is likely less than 50 animals. At present there is no evidence of breeding and there has been extensive loss and degradation of suitable habitat. Marten were trapped extensively throughout Nova Scotia since the 1700s until the season was closed in the early 1900s due to low numbers. The species was thought to have been extirpated from the mainland, and several re-introductions have been attempted. There have been some very recent records of Marten in southwest Nova Scotia. However, the status of the Marten on the mainland is considered "data deficient." More research is required.

Canada Lynx

Lynx formally occurred in areas of suitable habitat across mainland Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island. The current population is very small and restricted to two areas in the highlands of Cape Breton Island. Historic and current threats to Lynx include harvesting, competition from bobcats and coyotes, habitat loss, disease, and climate change.

Mainland Moose

The native population of moose in Nova Scotia is limited to about 1000 in isolated sub-populations across the mainland. The population has declined by at least 20 per cent over the past 30 years, with much greater reductions in distribution and population size over more than 200 years, despite extensive hunting closures since the 1930s. The decline is not well understood, but involves a complex of threats including over harvesting, illegal hunting, climate change, parasitic brainworm, increased road access to moose habitat, spread of white-tailed deer, very high levels of cadmium, deficiencies in cobalt, and possibly an unknown viral disease.

Moose on Cape Breton Island are not risk as they are abundant and the result of a re-introduction of moose from Alberta in the 1940s.

Boreal Felt Lichen

This small, inconspicuous lichen has experienced a dramatic decline of over 90 per cent in occurrences and individuals over the last two decades. Boreal Felt Lichen is now known in Nova Scotia from only one site that includes three individuals all within an area of only a few hundred square meters. The primary threats to Boreal Felt Lichen are atmospheric pollutants and acid precipitation, which can cause the death of individuals and disrupt reproduction. The lichen can also be threatened by forestry and other land use practices if they disrupt the moist microclimate that is essential for the species.

Wood Turtle

There may be 2,500 Wood Turtles widely dispersed across river habitats in Nova Scotia, but information suggests that this species is declining. Like other turtles, this species is of concern because even low mortality rates of adults can have serious population impacts. Threats to wood turtles in Nova Scotia include alteration and destruction of river and stream habitats and translocations of turtles by people.

Bicknell’s Thrush

Bicknell's Thrush is of concern because of habitat change, low numbers, patchy distribution, and low reproductive potential. However, little is known about this secretive species. It breeds in Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and the northeastern United States. In Nova Scotia, it is currently restricted largely to Cape Breton Island, although historically it was found on a few offshore islands in the southwest part of the province. Habitat has been altered in Nova Scotia over the last century by infestations of spruce budworm and forest management practices

Eastern White Cedar

Cedar is an uncommon tree in Nova Scotia and currently only 32 stands in five counties have been identified. The population is fragmented and comprised of mostly small stands that appear genetically separate from each. Most populations are different from populations in NB and PEI. Almost all of the cedar is located on private land and only one stand is formally protected. In the recent past, stands have been lost to forest harvesting and highway construction. Ornamental cedars of the same species have been planted around homes and in gardens; these trees are not considered part of the native population and are not covered by the listing under the act.

General Status of Species in Nova Scotia

Besides those species designated by the NS Endangered Species Act, there are many other Nova Scotia species that occur in low numbers or have limited habitats and these have not yet been elevated to a legal status. The General Status Assessment process is a "first alert" system that provides an overall indication of how well species are doing in Nova Scotia. http://www.gov.ns.ca/natr/wildlife/genstatus/

The website above is a neat web site where knowledgeable groups of botanists, zoologists, and other scientists in Nova Scotia have ranked the rarity of vascular plants, birds, mammals, amphibians, reptiles, and several invertebrate groups. Red status means known or thought to be at risk; Yellow, sensitive to human activities or natural events; and Green, not believed to be sensitive or at risk.

Woodlot owners, if finding and identifying an unusual species, could check this web site and determine the status of the species. As an example, the database gives the status of 1115 vascular plant species.

|

|

Joan Barr identified Canada lily on her woodlot where it grows close to a stream. Carl told her that it has provincial Yellow status. |

|

|

|

| STATUS | VASCULAR PLANTS |

| Red |

170

|

| Yellow |

144

|

| Green |

703

|

| Undetermined |

98

|

|

|

|

COSEWIC and SARA

COSEWIC stands for the Committee on the Status of Endangered Species in Canada. SARA stands for the Government of Canada Species at Risk Act.

In 2004 the federal government enacted the Species at Risk Act. The federal government relies on the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) to decide which species are designated by SARA. COSEWIC is an independent committee of scientists that assesses and designates which wild species in Canada are in danger of disappearing. On the recommendation of COSEWIC the federal government makes a decision to list a species under the Species at Risk Act.

Including the year 2006, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Species in Canada has included 529 species of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes, arthropods, mollusks, vascular plants, mosses and lichens as Extinct (13), Extirpated (22), Endangered (205), Threatened (136) and Special Concern (153).

Many of the COSEWIC species are already identified in the Nova Scotia list. Additionally listed by SARA for Nova Scotia are:

Endangered – Eskimo Curlew and Bay of Fundy Atlantic Salmon

Threatened – Striped Bass

Special Concern – Rusty Blackbird, Barrow’s Goldeneye Duck, Ipswich Sparrow, Short-eared Owl, American Eel, Frosted Glass-whiskers Lichen, and Monarch Butterfly

Environment Canada's Species at Risk Website

Federal government species at risk website containing information on species at risk in Canada, federal legislation, searchable database, funding opportunities information, and more.

http://www.speciesatrisk.gc.ca/

Becoming a Better Naturalist

This module has several references to books and websites. Many are the books that Joan Barr and Carl use. Learning to identify plants and other wildlife on a woodlot can greatly enrich your enjoyment of the woodlot. Importantly the woodlot owner will become a better land steward, learning to identify species of conservation concern.