Module 15: Pests of the Acadian Forest

Lesson 1 Getting Started

To get started on understanding pest damage, you need to know not only about the pests themselves but also about the trees they infect. For this reason, Lesson One provides a quick review of tree species and tree parts as well as some basic information on pests. Together these build a useful background for understanding the terms and processes you’ll find in this module, in the field guide, and in your search for answers.

This Lesson looks at:

• Impacts of Insect Activity

• Identifying Pests by Host Tree

• Parts of the Tree

• Insect Types

• Insect Life Cycles

• Invasive Alien Species

• Integrated Pest Management

• Insects and Climate Change

• What to do if your woodland is infected

(a general overview)

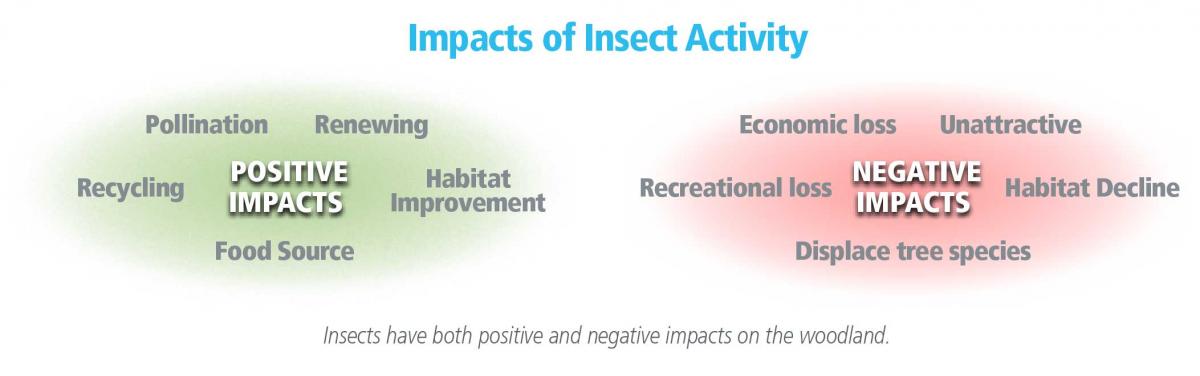

Positive Impacts

The most important parts of the identification process are knowing what species of trees are infected and a visual inspection. In most cases (about 70%), the insect will have left the infected trees by the time the damage is noticed and only the effects remain. The insect may be travelling to other trees; however, it may be possible to prevent or slow down further damage.

The most important parts of the identification process are knowing what species of trees are infected and a visual inspection. In most cases (about 70%), the insect will have left the infected trees by the time the damage is noticed and only the effects remain. The insect may be travelling to other trees; however, it may be possible to prevent or slow down further damage.

Insects play necessary and beneficial roles in the forest ecology. One of the more obvious roles is insect pollination which creates new seeds. The forest is also renewed when insect activity kills old and weak trees allowing new growth. The dead trees are recycled by insects into soil and can be used as habitat by certain birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals. Insects are also an important food source for many species of wildlife. Some insects feed on those insects that are harmful to the woodland helping to reduce the population of harmful insects.

Negative Impacts

Insect activity also can have negative impacts in the forest, especially if the damage becomes widespread. It can reduce growth, cause deformity, and dieback, resulting in reduced tree value for the woodland owner. Infected Christmas trees may not be sellable due to shipping restrictions. An infected area may look unattractive and be less appealing for hiking or other outdoor activities. If trees in a large area die, recreational use and wildlife habitat may be reduced. The existing tree species could be displaced and replaced by less desirable ones.

Insect activity also can have negative impacts in the forest, especially if the damage becomes widespread. It can reduce growth, cause deformity, and dieback, resulting in reduced tree value for the woodland owner. Infected Christmas trees may not be sellable due to shipping restrictions. An infected area may look unattractive and be less appealing for hiking or other outdoor activities. If trees in a large area die, recreational use and wildlife habitat may be reduced. The existing tree species could be displaced and replaced by less desirable ones.

Normal versus unacceptable

Some insect damage is normal in a balanced ecosystem. A few trees damaged or killed on your woodland is probably ok, but when a population grows bigger and feeds over a greater area, the amount of damage can become unacceptable. This is often due to having a large available food source. It can also be triggered by favourable climate conditions. The insects and damage may affect neighbouring properties as well or much bigger areas. The outbreak boundaries follow the areas of food source and cross property lines.

Other causes of damage

It’s not always an insect pest that is causing a tree or stand to look “sick”. As mentioned in the introduction, there are tree diseases that can look like insect damage. For example, ash trees can get a orange spot on the leaves caused by a rust disease that is similar to damage caused by an insect.

In some trees, the insect and disease work together. With Dutch Elm disease, an insect carries the fungus that later kills the tree. In beech trees, damage caused by feeding insects allows a fungus to enter later and damage or kill the tree. A suitable treatment may target the insect before the disease can spread.

Overly dry or wet soil can also cause trees to look damaged. After a wet season, water can pool in low areas and make Christmas trees look yellow.

In a dry season, needles can fall off and leaves can discolour. Once the tree is weakened, it may then be more susceptible to insect pests.

Identifying Pests by Host Tree

Identifying the host tree

A first step to identify the pest is to determine the tree species “hosting” the insect on your woodland. Some insects have a preferred host species. This can be thought of as the pest’s “ favourite food”. The pest will sometimes feed on other tree species if they are nearby or the favourite food runs out. This means you may need to identify several host species on your woodland.

The mix of trees found in Nova Scotia, southern New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island is called the Acadian Forest. It begins in New York State and stretches through New Hampshire, Vermont and Maine to the Maritimes. Pockets of other forest types and some non-native trees can be found but Acadian forest is predominant.

The number of native trees in the Acadian forest is less compared to southern regions. There are 30 native trees in the Acadian forest, some more abundant than others. Nova Scotia also has about 15 introduced species such as Norway spruce, and 15 shrubs or bushes such as pin cherry that can grow to tree size.

Softwood or Hardwood

A basic division for identifying trees is softwoods and hardwoods. Softwoods, also known as coniferous trees, always have needles on them. That is why they are called “evergreens”. The needles do shed - just look at the forest floor under a pine tree - but not all at once. The exception is the tamarack tree (also known as larch or hackmatack) which turns yellow in the fall and sheds its needles. The more common softwoods in Nova Scotia are spruce, fir, pine and hemlock.

Hardwoods, also known as deciduous trees, lose their leaves every fall after turning from green to a show of red, yellow and orange. They are usually bare in winter (a few dead leaves sometimes hang on) and bud out again in the spring. The more common hardwoods in Nova Scotia are maple, birch, poplar and oak.

Tree Species

Many woodland owners will already know the more common kinds of softwood and hardwood trees but may not be as familiar with the various groups or species of trees, for example red, white and black spruce. These can be easily identified by examining the bark, needles , leaves and/or seeds. Module One “Introduction to Silviculture” has descriptions and sketches of nine softwood species and eleven hardwood trees to guide you. Another good resource is the book, Trees of Nova Scotia. (See Appendix A).

Naming Pests

Some pests are named for their appearance such as the whitemarked tussock moth. Others are named for the damage they cause such as the seedling debarking weevil. Many pests are named after a tree species that they damage such as the spruce beetle.

However in the complex world of insects, naming is far from standard. The pest and the tree species it is named after may not have a one-on-one relationship.

Some Examples:

1 Many pests will attack other species in addition to the tree species in their name. That species may be the preferred host but not the only host. An example is the balsam fir sawfly that prefers Balsam fir but also feeds on spruce.

2 For other pests, the preferred host may not be reflected in the name. The spruce budworm, for example, prefers Balsam fir but will also feed on spruce.

3 The pest host may not apply to the Acadian Forest. The hemlock looper prefers hemlock in western Canada but likes Balsam fir in eastern Canada.

These examples may be helpful as you read about pest names and try to determine which one is causing the damage.

Christmas Tree Pests

Christmas trees are an important industry in Nova Scotia. Most of them are Balsam fir which has more than its fair share of pests. In a Christmas tree stand, there is a concentrated food source that can encourage population growth and certain pests can cause considerable damage. The field guide includes descriptions of the more common Balsam fir pests. For producers who need more detailed information and treatment options, material is available on line and in print. (See Appendix A.)

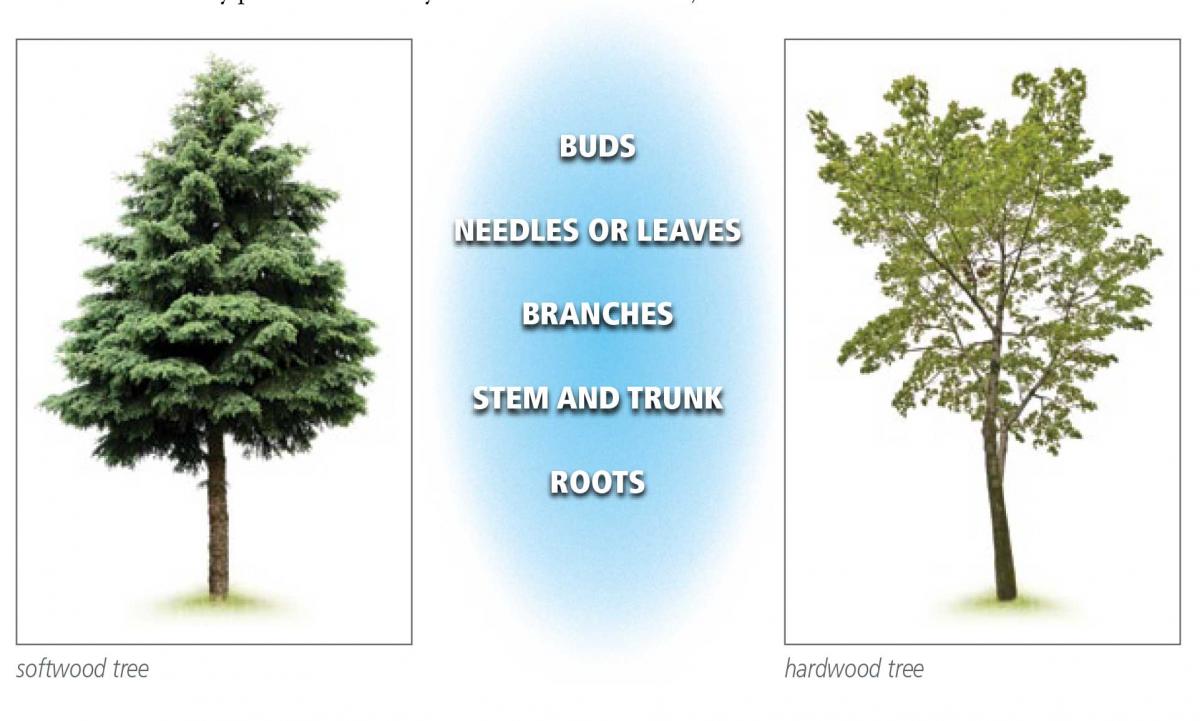

Parts of the Tree – Softwood and Hardwood

Each insect species tends to attack a specific part of a tree like the needles or the bark. Since this information is part of the identification process, tree parts are reviewed below for both softwood and hardwood trees. The insect world is full of exceptions and a few pests will feed on more than one part of the tree.

Note: While many pests feed only on softwarood or hardwood, some feed on both.

For studying insect damage in this module, the tree is divided into FIVE parts:

Insect Types

The insect world is complex with over one million species of insects that change appearance as they go through their life cycle. Fortunately, the most common insects found causing damage to your woodland can be grouped into five general types that most people can recognize in the adult stage. In general, insects do the most damage during the larval stage.

1 beetles

Larval damage by beetles may include boring under bark and into stems, and foliage feeding. Adults may cause damage to stems during egg laying (ovipositing) or while feeding on foliage, bark or stems.

2 moths

Moths do all of their damage in the larval stage by feeding directly on the foliage, mining the foliage or boring into stems. Adults for the most part do not damage vegetation.

3 flies

Adult flies do very little damage and are responsible only for egg laying and reproduction. Fly larvae can cause a variety of damage including gall production on stems and foliage.

4 Wasps

Wasp pests include larval defoliators, gall makers, foliage miners and wood borers. Adult pest species may cause damage to stems and foliage during egg laying as well as some minor feeding damage.

5 True bugs, aphids or hoppers

Both immature and adult stages of these insects cause damage. Immature stages are called nymphs – miniature versions of the adults – and have no true larval stage. Nymphs feed in a way similar to the adult, causing damage by sucking plant juices from either foliage or stems.

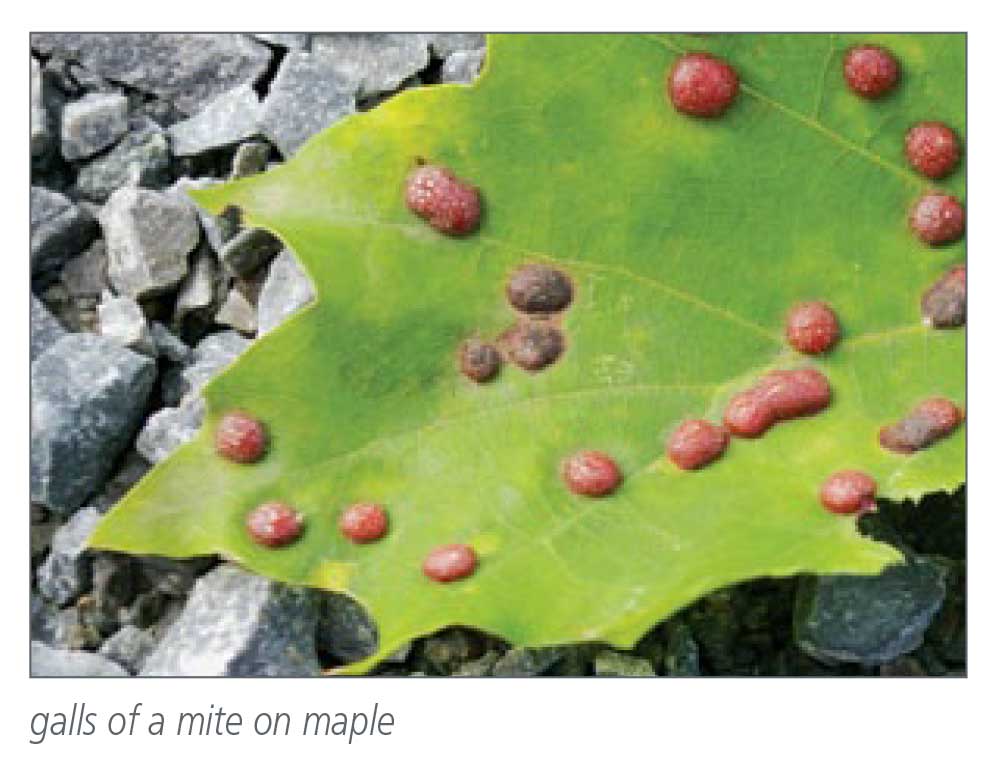

6 Non insect forest Pets

Mites

Insects are defined as having six legs, three body parts, an exoskeleton (a hard shell outside the body) and most have wings. The classification does not include spiders, ticks, mites or certain other animals similar to insects. Mites however are discussed in this module as they are a significant pest of our forest.

Mites are not insects and are more closely related to spiders. They can however cause significant damage to foliage during feeding with their sucking mouthparts.

Insect descriptions include the habits and appearance of the insect during all stages of its life cycle. Knowing what a species looks like during each stage will help you identify the insect if it is still present. Recognizing the insect stage is necessary for timing a treatment to prevent or limit further damage.

Four Stages in the Life Cycle

Insects go through four stages in their life cycle. You may remember these from school days.

To add to the complexity, each insect species has its own variations on these four stages. For example, spruce budworm has six larval forms before it makes a pupa. The balsam twig aphid has several adult forms in its life cycle.

This means that each pest looks very different at various stages in its development. Fortunately, research has provided us with specific details on the life cycle of woodland pests.

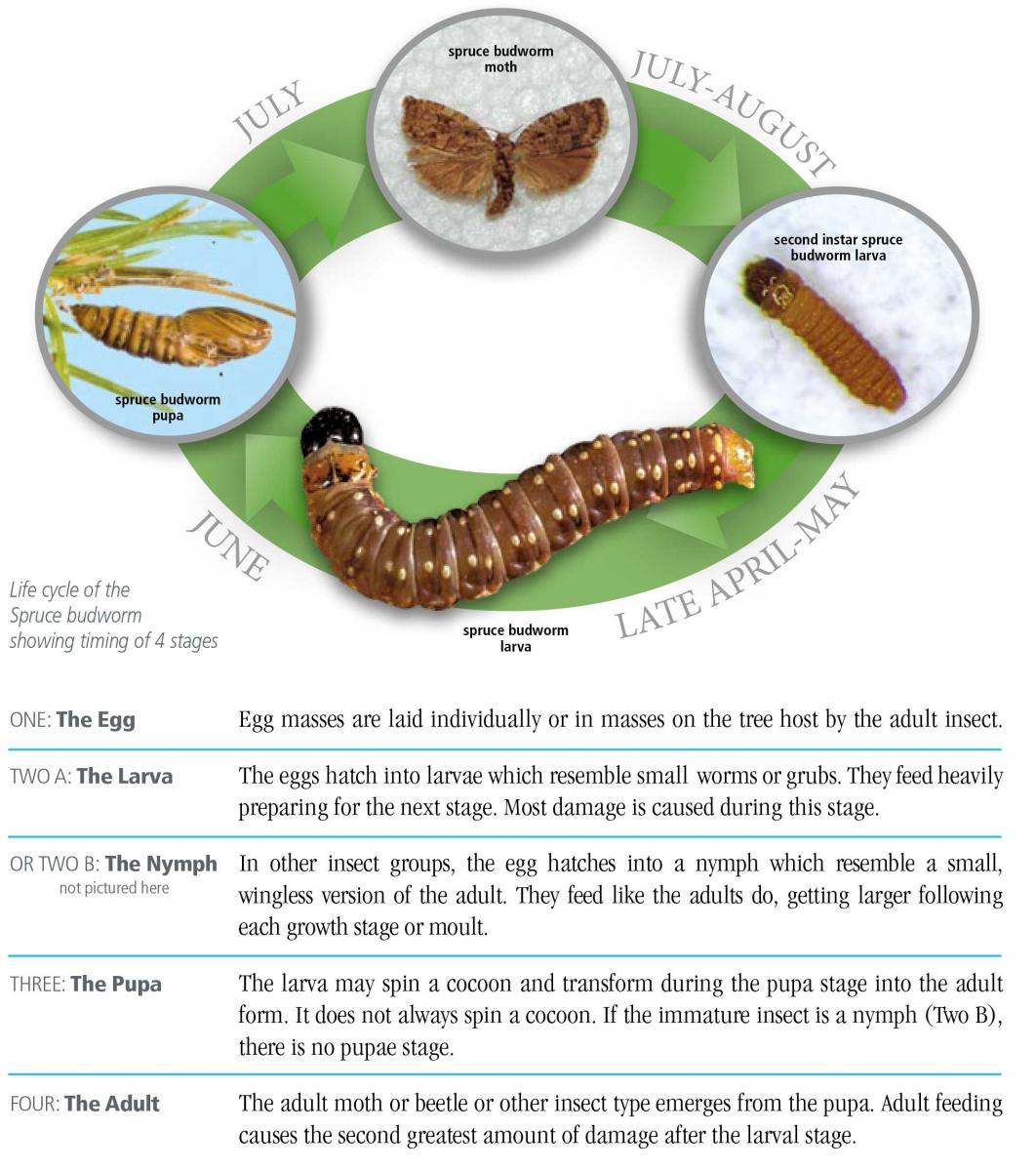

Spruce Budworm

Order: Lepidoptera

Family: Tortricidae

Latin Name: Choristoneura fumiferana (Clemens)

Common Names: spruce budworm, eastern spruce budworm

Introduction

The spruce budworm has caused more damage to Nova Scotian softwood forests than any other insect. Overmature balsam fir is the preferred host and acts as a flash point for rapid population buildup. Populations tend to increase steadily and spread to younger trees. Feeding takes place on the top third of the tree on new shoots. High populations will result in repeated loss of all new foliage which will kill the trees within 3 to 4 years.

Sample insect Profile

All this information – host tree, life history, damage symptoms, and possible controls – is pulled together in the insect description or profile.

For example, here is the profile for the spruce budworm from the Department of Natural Resources web site.

Life history

In late August or September, the eggs hatch, the larvae moult, and overwinter in the second instar. In late April or early May, the larvae (3 mm long) emerge from their hibernacula and begin to feed, mining the needles and buds. A week later they move to feed on the closed buds and any developing shoots. The larvae are fully grown within five weeks. They have black heads and a dark brown body, (18 - 24 mm long). They pupate on the foliage and the adult moths emerge in July to lay eggs which hatch in 2 to 3 weeks. The adults are dull grey with a wingspan of 20 mm.

Damage symptoms

Defoliated trees over large areas with red foliage; particularly the new foliage on the upper third of the tree.

Control options

Harvest stands of overmature fir and spruce to remove potential population build up sites. Biological control products are recommended for large forested areas. These will not interfere with naturally occurring parasites and diseases that help control budworm populations.

For ornamental fir and spruces, both biological or contact insecticide can be used. When using a biological insecticide such as Btk (Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki, see glossary), the product should be applied while the larvae are in the open and feeding. Contact insecticides should be applied while the larvae are exposed and not hidden under the bud caps.

Exercise:

Read through a few insect profiles to get familiar with the type of information they contain. You can find some on line at the DNR web site, the Canadian Forest Service web site and in the Field Guide. Insectary Notes also has a longer profile in each issue. (see Appendix A for the list of web sites).

Invasive Alien Species

Insects may appear on your woodland that are not native to the area and have traveled outside their usual range. These are known as invasive alien species. They may originate from outside Canada or from other parts of Canada. An insect can be alien even if it is native to Canada when it extends beyond its usual geographic range. The term alien refers to shifts across ecosystems, not simply across borders.

The introduction of these insects is often accidental. The insects can arrive in plants or wood products brought in from other countries. They can spread from their original arrival point to other areas with suitable food. A recent example is the brown spruce longhorn beetle, which is native to Europe. It arrived by sea in the wood of packing crates into the port of Halifax. At first it was found close to the shipping terminal in the trees of Point Pleasant Park but it has now spread to some other areas of the province.

The alien insect becomes known as invasive if it has spread beyond its usual range, adapts to the host area’s ecosystem and causes extensive damage. The Government of Canada definition is “Invasive alien species (IAS) are plants, animals, aquatic life or micro-organisms that outcompete native species when introduced outside of their natural environment and threaten ecosystems, economy and society.” (2009). From Invasive Species Alliance of NS.

The Gypsy Moth is an example of an invasive alien species. It was imported from Europe to the US over one hundred years ago in an unsuccessful attempt to help the silk industry there. It feeds on more than 400 species of trees and has historically caused serious defoliation to hardwoods in Nova Scotia.

As the climate changes and trade increases, insects are moving into new ranges. Some species have a tough time adapting to the new environment and do not become invasive. Others may do well as they have no natural enemies in the new location, resulting in negative impacts. Like native pests, they can cause extensive damage in pure stands or stands with a high percentage of one species where they find a large available food source.

See Appendix A for more information on the effects of Invasive Alien Species and details on specific insects.

Integrated Pest Management

Because the world of pest insects is so complex (both the insects and their habitats), the management of these pests is also a complex and evolving science. In the past, the two main treatments were pesticide spraying and salvage harvesting but now they are just two of many tools available to the landowner.

As knowledge improves, a more integrated approach to pest management has evolved. Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is an effective method to manage forest pests. It looks at all appropriate options considering both the economic and environmental impacts.

By better understanding insect life cycles and their interaction with the environment, new tools are being developed to monitor and, in some cases, reduce the spread of insect pests. These include products that target the behavior and biology of the pest. Improved methods of detection include development of more effective traps and more specific attractants.

Chemical sprays are being replaced or used along with safer biological products such as viruses and fungi. Some beneficial insects can be used to minimize the damage of pests; this is known as biological control. These biological products can target specific species of pests, reducing the impacts of the sprays on non-target species and sensitive ecosystems.

The effect of some treatments can be hard to predict in the intricate ecology of the forest. In recent years more emphasis is being placed on risk analysis and prevention. It’s a good idea to examine the potential risk a pest may have on your woodland before control efforts are made. This may reduce the chances that the treatment causes new problems such as eliminating a beneficial insect or prolonging an infestation.

In some cases, costly control measures may not be necessary. Practices such as breaking up the forest age class, promoting a healthy mixed species woodland and selecting pest-resistant varieties are preventative methods that can be very effective, cost-efficient and low risk to the environment.

Managing your woodland for forest pests should no longer consist of a single control method but rather a series of pest management evaluations, decisions and controls. Think of it as having a toolbox full of possible solutions instead of just one hammer.

Insects and Climate Change

As science is showing, our climate is changing and this in turn changes our forests. Wetter winters, drier summers and more wind storms can stress the forest and affect which tree species grow well here. More exotic diseases and pests may be an additional stress.

As the climate changes, so do the insects living in the forest. Some may thrive and others may decline. For example, a DNR employee has noticed that the balsam woolly adelgid is now active in the Cape Breton Highlands where it was not found 25 years earlier. He says, “The winters were too cold before and the insects did not survive. Now in 2013, the insect is active in all of the highlands where balsam fir is found. It takes a sustained temperature of about -25C or lower to kill the insect and we rarely see those temperatures anymore.”

As new tree species begin to flourish, new insect species will grow along with them. What does this mean? We have to be aware that these shifts are occurring and learn new ways to adjust our management techniques to address them.

What to Do if Your Woodland is Infested

A woodland infestation can range from mild to severe. The level of damage can be predicted by estimating the number of insects present. For small scale infestations, it may not be necessary to do anything. Damage may be limited to a few trees. If the wood is infected and has the potential to spread, it is common to cut up the wood and remove it or chip it. In a severe case, it may be necessary to do a more extensive cut or use insecticide spray.

What you want to get out of your woodland (your woodland objectives) also influence how you choose to manage the insect infestation. What one woodland owner considers a serious infestation may not be of great concern to another. If your objective is income and an insect is attacking a stand of trees you are growing to sell later, you may want to act quickly. If your objectives for the infected area are recreation or habitat, then an infestation may not affect those objectives as much.

If the insect is still present, identify the host tree and collect a sample of the insect. Also collect a damage sample if possible, for example a damaged leaf, and also a healthy sample. Lesson Four explains how to collect and send samples. Make a note of the type of damage and walk your woodland to determine how widespread it is. Remember that damage can also be caused by diseases and moisture conditions.

If the insect is not present, you can still narrow it down by identifying the tree host and the damage symptoms. Collect a healthy sample and one showing damage. Lesson Two and Three outline the various kinds of damage, the associated insect types and some control options. Sometimes different insects can cause the same damage but the control options are the same.

Use the field reference guide to try and identify the specific insect. You can also consult with Pest Detection Officers (PDO) at the local DNR offices, the Forest Health Specialists and Entomologist at the DNR Insectary, or a forestry consultant for help with identification and suggested treatments.

The woodland or forest owner – private, municipal, provincial or federal – is responsible for pest management. If your woodland infestation is widespread, it may be that neighbouring lands are also infected since pests follow food and are unfamiliar with property lines. You may want to work with neighbouring landowners on an integrated management approach if the infestation extends beyond your woodland.

Review

If there is an infestation on your woodland, try to identify the insect (even if it is gone) to determine what action is needed, if any. The host tree, the appearance of the insect, and the damage it causes are all key factors in identification. By paying attention to signs of infestation, you may be able to prevent damage to your trees or reduce the spread of the insect.