Module 1: Introduction to Silviculture

Lesson One - Introduction

Importance of Our Forests and the Forest Industry

Diverse, healthy forests are vital to the well being of our planet. Forests are complex, living systems that are home to a variety of organisms. They protect our soils, rivers and lakes and are a valuable recreational resource. Even the quality of the air we breathe depends, to a great extent, on forests. Trees store carbon and absorb carbon dioxide (especially fast growing ones), thereby reducing the greenhouse effect.

|

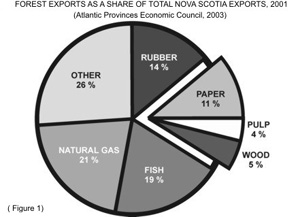

Economically, the forest industry is vital to Canada and Nova Scotia. (Figure 1) Nationally, in 2003, the industry contributed over $33 billion to the gross domestic product; almost $40 billion to our exports; and $29.7 billion to our balance of trade (Natural Resources Canada, 2004).

Provincially, in 2003, forestry contributed to our economy through more than $923 million in exports; and over $873 million to our balance of trade. Over 13,000 jobs result directly from the forestry industry in Nova Scotia (Natural Resources Canada, 2004).

To maintain this industry, approximately 6 million cubic meters (m3) of roundwood is harvested each year in the province (Natural Resources Canada, 2004). Sixty percent of this wood comes from small private woodlots, which cover 50% percent of the forested land base in Nova Scotia. The land is owned by over 31,000 small landowners (Dansereau & deMarsh, 2003, Canadian Institute of Forestry, 2001).

The forest has provided Nova Scotians with a way of life for many generations. If we are to maintain a healthy productive forest in the future, it is important that everyone understand the forest and practice sustainable forest management.

|

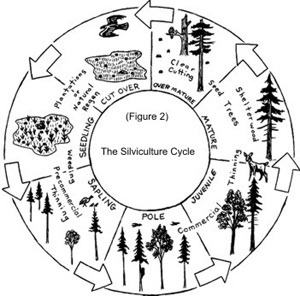

Understanding trees and how they grow is basic to the practice of silviculture. Silviculture is the practice by which stands are tended, harvested and replaced by new stands to meet specified objectives. It includes the “green circle” from artificial regeneration or natural regeneration to harvesting (Figure 2).

The intent of this module is to help readers understand some basic characteristics of tree species which are important to the practice of silviculture. It does not discuss silviculture techniques, or the related subject of forest ecology; these are dealt with in modules 2,3,5 and 7 respectively.

The Forest of the Past

As the original inhabitants of this province, the Mi’kmaq, occupied most of the land prior to the arrival of the European settlers. The First Nations people had a unique relationship to the earth’s resources, engaging in various life-supporting activities, ranging from hunting and gathering, to agricultural activities. They believed that the richness of the earth was provided by their Creator. The Aboriginal peoples assumed a role of stewardship and pursued their activities guided by principles of respect and responsibility to the land and natural resources (NSDNR, Education Module).

The first Europeans had a different view of the seemingly endless forest of pine, spruce, hemlock and majestic hardwoods. They saw the forest as something that had to be conquered if they were to survive.

The same forest that initially presented an obstacle to the survival and success of the new settlers soon became a source of wealth. The best white pine trees were cut and exported to supply the world shipbuilding industry. Later, the demand for spruce and hemlock lumber fed the local and export markets. When the supply of sawlogs dwindled, pulp mills were established and areas previously cut were recut. Each time the forest was cut, only the biggest and best trees were taken. The removal of the very best trees is called selective harvesting or high-grading and was a common practice. In many cases, only the poor quality trees were left. Since these trees were the main seed source, they tended to produce poor quality, sparse stands of low volume.

The attitude of most people at that time was that the supply of wood was endless. It didn’t take long before the forests of Nova Scotia consisted of poor quality trees. A study conducted by Fernow (a noted forester) in 1909-1910 concluded that the forest was:

“largely in poor condition, and is being annually further deteriorated by abuse and injudicious use because those owning it are mostly not concerned in its future and do not realize its potentialities”.

Disturbances like fire and insect outbreaks have also shaped our forest. Fires, like those caused by lightening, are a natural part of the forest ecosystem. During the early 1900’s, fire was used to clear land. These fires accidentally spread into the surrounding forest and destroyed thousands of acres of merchantable timber. A fire prevention and suppression program began in 1927, when the amount of damage caused by these man-made fires was realized. Trees are also susceptible to insects and disease. While they are a natural occurrence, they can adversely affect the economic quality of our forest.

Clearcutting began in the late 1960’s and 1970’s with the introduction of mechanical logging equipment (Johnson, 1986). While it is an appropriate harvesting system in some forests, clearcutting was often not done properly and has produced some poor quality forests. It removes all merchantable trees from an area at the same time. Large clearcuts tend to regenerate with species, such as trembling aspen, pin cherry, and red maple. These species have less economic value and are the pioneer species of the Acadian Forest.

Woodlands were not always properly managed in the past because settlers lacked the knowledge; there were few established guidelines, and there was limited revenue. Many operators were simply unaware of the long-term effects of high-grading. Minimal returns on stumpage did not encourage reinvestment in the forest, and legislative guidelines for harvesting methods were not enforced.

The Forests of Today

Nova Scotia is located in the Acadian Forest Region of Canada. This is a relatively small region covering nearly all of Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and southern New Brunswick. It is a transition zone between the southern deciduous forest and the coniferous forest to our north (Farr, 2003). The Acadian Forest is characterized by a variety of coniferous and deciduous tree species. In all there are 30 tree species that are native to the Acadian Forest (Saunders,1995).

The demand for forest products has increased significantly over the past ten years. This has lead to significant harvest increases, especially on private lands (NSDNR, 1997). With approximately 50% of the productive forest in private ownership, it is essential that woodlot owners practice good management, for wood production, biodiversity, wildlife, water quality, recreation and other values.

The provincial government recognized the values of private woodlots in its 1986 ‘Forestry Policy’. This policy “encouraged the development and management of private forest lands as the primary source of timber for industry in Nova Scotia” while ensuring owners “continued to enjoy the traditional rights and responsibilities of private ownership of land.”

In 1997, the provincial government produced ‘Toward Sustainable Forestry: A Position Paper’ to reflect evolving values and concerns, as well as society’s changing needs and expectations for stainable development. The ‘Forest Sustainability Regulations’, enacted in 2000, require certain forestry companies, based on their annual volume of wood acquired, to undertake annual silviculture work on private land. (Private land means all lands excluding Crown land.) Companies can meet the requirements of these regulations by carrying out a silviculture program on private lands, by contributing money to a special fund called the Sustainable Forestry Fund, or some combination of both. The intent of the new regulation is to increase the amount of silviculture work on private lands (NSDNR, 2000a).

The total gross merchantable volume for all species in Nova Scotia is 404 million cubic metres (168 million cords). Of this, 70% is softwood (282 million cubic metres or 118 million cords) and 30% is hardwood (122 million cubic metres or 50 million cords) (Townsend, 2004). Harvesting on Crown and industrial lands has remained within potential wood supply limits while softwood harvesting on small-private woodlots has increased in recent years (Atlantic Provinces Economic Council, 2000). As a result of the Forest Sustainability Regulations, increased silviculture should be able to offset this rise in harvest level.

Because the best land was granted to the public, small private woodlots tend to have a higher net growth rate than those of Crown lands. Therefore, silvicultural investment on private woodlots usually generates a relatively higher return. The average growth rate for Nova Scotia forests is 2.0 cubic metres per hectare per year (0.9 cords per acre per year). With the use of appropriate silviculture, this growth can be increased to an estimated 5.5 m3/ha/yr. (2.5 cd/ac/yr)(NSDNR, 2000b).

A combination of knowledgeable, committed land owners, cash incentives for silviculture programs, tax incentives, public education, legislation, and increased wood prices are necessary for well managed woodlots. Past winners of the Woodlot Owner of the Year Program provide evidence that N.S. has keen and knowledgeable woodlot owners. Cash incentives are being provided by Provincial and industry programs, such as the Forest Sustainability Regulations. These home study modules and similar courses help landowners learn more about forest management and legislation such as the Wildlife Habitat and Watercourse Protection Regulations ensure valuable habitat is protected on all land.

The Future Forest

Depending on species, a forest may take 40 to 100 years to mature. Consequently, we must practice sound management today to ensure productive and healthy forests for our children.

|

We must harvest with the future in mind. This means leaving the best trees as a seed source so that new trees are of good quality and health. This means ensuring there are adequate buffers along water ways. It also means managing for a variety of species, because a diverse ecosystem is stable and is better able to handle disturbances. These are some of the aspects woodlot owners must address when deciding how best to manage their land to meet the needs of society and woodlot owners today, and the needs of future generations.

Proper forestry practices must be the concern of everyone regardless of whether or not they work in the forest industry. We have used our forest to build a great nation. Now it is time to ensure the future forest is managed for a variety of values, species and age classes. Through education, financial incentives, tax incentives and appropriate legislation, diverse healthy forests will be sustained.