Module 5: Stand Establishment

Lesson Three - Artificial Regeneration Management

Artificial regeneration of softwood begins when cones are collected from the forest or from special seed production areas called seed orchards. Seed orchards contain trees grown from seed or shoots from the very best trees, often called "plus" trees. The seed are extracted mechanically and stored under controlled conditions.

Seeds are germinated and grown into seedlings in forest nurseries. Softwood species dominate artificial regeneration programs. Hardwood seedlings are more difficult and expensive to produce and planting success is poor. This text will deal exclusively with planting softwood.

In 1989, approximately 10 million trees were planted on small woodlots in Nova Scotia. At 3100 trees per hectare (1200 trees/acre), these trees occupy about 3,400 hectare (8,300 acres). In addition, approximately 15 million trees were planted on crown and large company lands in 1989.

An owner whose woodlot is dominated by healthy red spruce, yellow birch, sugar maple, and beech may not understand why we need to plant so many trees. This is especially confusing when it seem that the forest can regenerate itself, as discussed in Lesson 2. The forests of the province can be quite different from one area to the next. A woodlot owner in Cape Breton whose balsam fir and white spruce stands have been devastated by spruce budworm and spruce bark beetle during the past 155 years may not have an option other than to clearcut the site and replant to restore productivity.

Planting is usually recommended on private woodlots in the following cases:

-

mature and overmature stands that will not likely regenerate naturally, such as white spruce, or that will regenerate to undesirable species.

-

non regenerating, understocked, stands, regardless of species composition, since the site is not being fully utilized, if it will not likely improve.

-

young stands stocked with low value species such as grey birch, white birch, aspen or beech.

- stands that have been damaged by insect, disease or fire and which will not regenerate naturally.

PLANNING

As with natural regeneration, the most important thing to do before making the final decision to plant is to walk though and thoroughly assess the stand prior to harvest. This will:

-

reveal the presence of regeneration on the forest floor, or the potential for future regeneration. Generally, small cutovers of less than 2 ha (5 ac.) that have good adjacent seed sources will regenerate satisfactorily. It is unnecessary and wasteful to plant areas that will regenerate naturally.

-

indicate the potential hazard for rabbit browsing in the area. Rabbits can browse up to 10 rows of seedling along the edge of cover, which may be 75 percent or more of the trees in a small plantation. Regardless of species, rabbits prefer nursery grown seedlings to natural seedlings because of their high nutrient value. Large plantations without weed control also provide good "cover" for rabbits and are high risk for browsing.

-

identify and predict the vegetation, other than trees, that may affect the future plantation.

- uncover any insect or disease problem common in the area.

Note:

All softwood and mixedwood cutovers must be left for two years before planting to eliminate the risk of damage by the seedling debarking weevil which lives in new slash. This will also provide an opportunity for natural regeneration to become established.

Use the following criteria to decide which method of harvest may be best when site preparation and planting are included as part of the total operation:

Ecologically

Which method will minimize site disturbance and nutrient removal and reduce the risk of fire?Financially

Which method will pay the highest stumpage rates and result in the lowest future treatment costs (e.g. site preparation)?Technically

Is there sufficient landing space for the various logging systems available?

Is risk of seedling debarking weevils high?Finally

What type of harvest is best for your particular stand versus what is available? Do you have a choice?

If your assessment indicates planting is needed, plan for the following aspects of the operation:

(a) harvesting method

(b) site preparation

(c) planting

(d) plantation maintenance and weeding

Good planning may allow you to do something at one stage that will make future treatments easier and cheaper. The most successful artificial regeneration efforts usually begin with a well planned harvest operation. As an example, you may be able to harvest in a way that will eliminate the need for site preparation.

Now let's discuss these aspects of artificial establishment of a stand.

Harvesting Method

In Nova Scotia, harvesting is carried out in one of the following methods:

-

Whole-Tree Harvest: Trees are felled, skidded or forwarded to roadside, with limbs and tops, leaving a relatively bare site.

-

Shortwood Harvest: Trees are felled, delimbed, and bucked to length at the stump leaving limbs and tops on the site. Wood is carried to roadside by a forwarder or tractor-wagon.

-

Tree-Length Harvest: Trees are felled, delimbed, and skidded tree length to the landing.

- Random-Length logging is a system similar to #3. Random-length products are skidded or forwarded to a landing.

Site Preparation

The primary objective of site preparation is to create as many suitable planting spots as possible. Suitability for planting means easy access for planters and sufficient suitable microsites for seedling survival and growth. These microsites generally have adequate drainage, mineral soil and humus mixture, and minimal weed competition.

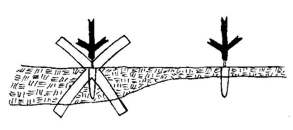

Sites logged using the whole-tree harvest system may not require site preparation because the site is generally clear of logging slash. On sites logged using the shortwood or tree-length systems, limbs, tops, and unmerchantable debris may hamper the ability of planters to reforest the area. In this case, slash must be reduced or rearranged by one of the methods shown in ( Figure 11 ).

The brushrake and burn system was the site preparation method most widely used in Nova Scotia. The popularity of this system has declined because of concerns about fire hazards and nutrient loss associated with burning. The debris crushing system and corridor raking will likely become more popular since most logging debris stays on the site. The possible serious environmental impacts, including nutrient loss from whole tree harvesting, is a concern for both public and some forestry experts.

Planting

Lesson 1 described how each tree species competes under a particular set of site factors which include drainage, fertility, competing vegetation, and exposure. When deciding which species to plant, consider the site factors and choose the species that are likely to compete and grow best under the existing conditions.

A general guideline of species selection is given in ( Figure 12 ).

The following are examples of species that will do better on well drained, fertile sites, but due to their silvic requirements, they can survive on these less favourable sites.

- black spruce and larch are able to grow on wet sites.

- white spruce will do well on very exposed sites because of its ability to withstand salt spray, wind, and winter drying conditions.

- pines will grow on very dry, sandy sites with low fertility because of their deep rooting system and low nutrient requirements.

If the site is not suited to the species you prefer to plant, site improvements can be made by:

- ditching or ploughing to improve soil drainage

- fertilizing to improve soil fertility

- using mechanical or chemical weed control to help reduce competing vegetation.

Nursery Stock

When you have decided which species to plant, the following nursery stock types may be available:

|

|

|

|

Planting Spot Selection

Planters ultimately decide where each seedling should be planted. The following are general guidelines for choosing suitable planting spots or microsites:

-

Plant on the tops and sides of mounds, never in depressions where water will collect and roots will suffocate.

-

Avoid planting on rotten wood or thick duff because seedling roots need to contact mineral soil. Clean some of the duff way using your boot or planting tool.

-

Avoid bare mineral soil because frost heaving will likely occur.

-

Do not plant in excessively weedy or grassy spots because the competition may choke out the young trees.

Timing

Choosing the best time of year to plant will help increase the chances of success. Adequate soil moisture is the most critical factor affecting early survival and growth. For best results, plant in the spring soon after the frost leaves the ground (April 15-June 15) or in late summer (August 1 - September 15). Avoid planting during the potentially hot, dry period of early summer.

Seedlings planted after mid-September have less time to establish their roots and become more susceptible to winter drying or burning from insufficient snow which protects seedlings from winter winds.

Additional Planting Considerations

1. Markets

It is difficult to predict the changes in markets in 30-40 years. Red pine and larch currently have low market potential. However, specific products from these trees may have future possibilities. For example, good quality red pine trees will always be in demand for utility poles.

2. Old Fields

Grassy fields and pastures provide heavy competition for seedlings. Without using site preparation such as ploughing, white spruce and Norway spruce are the best choices.

3. Insect Damage

Are there common insects or diseases in your area?

White pine weevil occurs throughout the province and can severely affect young, healthy trees. Planting seedlings close together may help to reduce this problem, but will not eliminate it. You may want to discuss the situation with a local forester or forest technician.

As mentioned earlier, some areas of Nova Scotia have a small insect called "Hylobius congener" or "seedling debarking weevil" which causes severe damage in some newly established plantations. The weevils are attracted to newly logged areas and feed on the inner bark of freshly cut stumps and slash. When this food source disappears, the weevils turn to other food sources, which may be newly planted seedlings. Their feeding usually girdles the small seedlings which then die. In central Nova Scotia where the risk of weevil is high, logged areas are not replanted for at least two years after cutting. This gives the weevils time to eat and leave the site. Most forestry personnel in Nova Scotia are aware of the problem and can tall you how to proceed, depending on weevil risk in your area.

Plantation Tending

When seedlings are established, plantations should be tended to ensure that the young seedlings are sufficiently free of competition to grow properly. This is especially important during the first 5-10 years until the plantation is at a "free to grow" stage.

The establishment of plantations is similar to the pioneer stage of succession. After the mature trees are harvested, plants and shrubs will try to become established on the site. Examples of this vegetation include raspberry, grass, pin cherry, alder and aspen.

Let's look at the two types of competition that may affect young planted seedlings.

Competition for Space

-

Example: Red spruce planted on grassy fields

Without ploughing or chemical weed control, red spruce does not compete well against grass for root space. Seedlings may die or grow very slowly. Insufficient moisture and nutrients can result in pale green or yellow foliage.

Ploughing or using a registered herbicide before planting will usually reduce grass competition sufficiently for two or more years until seedlings are large enough to compete on their own.

Competition for Light

-

Example: Seedlings overtopped by raspberries

Seedlings may survive, but will be very spindly if they do. These frail seedlings are more susceptible to damage by the elements, especially snow.

Manually cutting the raspberries is extremely difficult and will need to be done each year since the raspberries can resprout after cutting. This is expensive, time consuming work and may only be practical for small plantations. The best method for breaking up dense raspberries in large plantations. The best method for breaking up dense raspberries in large plantations is chemical weed control, using a registered herbicide.

In Nova Scotia, ground or aerial application of registered herbicides is the most commonly used method of weed control in plantations. It is both economical and effective.

There are presently two types of herbicides registered for forestry use:

-

Root uptake herbicides such as Velpar L (Hexazinone) and Princep Nine-T (Simazine) are most commonly used for weed control before planting. These are applied in early spring when plants begin to grow. They work best if applied to just before light rains which moves the herbicide into the soil where it is taken up by the roots.

- Leaf intake herbicides such as Vision (Glyphosate) are usually applied in late summer (August-September) when softwoods have hardened off and are dormant. Hardwoods and other herbaceous plants are still actively growing and are killed by the application of Vision. This releases the conifers from the overtopping cover of weeds during the next growing season.

Chemical weed control reduces, but does not eliminate, the competition for light and space and gives the planted seedlings room to grow.

Manual weed control is not as effective or as feasible as herbicides since most competing vegetation sprout vigorously after cutting. Manual weeding would likely need to be repeated several times to ensure plantation success. Usually, herbicides need only be applied once during the life of a forest stand (40-80 years depending on length of the rotation).

APPLYING THEORY TO PRACTICE

Finally, let's look at two of the most common stand types that require a regeneration management strategy to guarantee productivity for the next rotation.

1. "Budworm damaged balsam fir and white spruce stands in Cape Breton"

Typical mature and overmature balsam fir and white spruce stands are 30-70 percent dead and have been dead for 4-5 years (in 1989). As these stands break up, light reaches the forest floor to allow establishment of patchy regeneration, and bare patches, these stands are a real mess. Well prescribed plantation management strategies for these bud worm damaged stand begin by:

(a) Developing a plan before harvesting:

The stand should be divided into two distinct operating areas if possible, based on a pre-harvest stand assessment.

Block 1: Area with satisfactory stocking of desirable regeneration.

Block 2: Area not satisfactorily stocked to desirable regeneration.

Each block needs to be large enough to make the operation economically feasible, 2-4 ha (5-10 ac).

(b) Harvest

Block 1: Organize felling and wood extraction to minimize damage to existing regeneration. Decide whether crushing the debris by dozer or roller will benefit future thinning operations, without seriously damaging the regeneration.

Block 2: Organize felling and wood extraction to facilitate efficient site preparation.

(c) Site Preparation

Block 1: Crush debris if beneficial; if not, leave as is.

Block 2: Brush rake debris into corridor piles or wait at least one year to use a crushing roller. Leaving slash to rot for 2 years can greatly reduce site preparation costs and result in a better job. If necessary, apply a root uptake herbicide such as Velpar L before planting to control competition.

(d) Planting

Order planting stock six months or more in advance for best selection. Order white spruce, Norway spruce, or white pine for sites with well drained soils; red spruce for well drained, sheltered sites (Cape Breton only); and black spruce for sites where drainage tends to be poor. Container or jiffy pot seedlings are preferred for ease of planting; small bareroot stock is second choice; and large bareroot stock should be planted where weed competition is expected to be a problem, Plant at 1.8m x 1.8m ( 6 foot) spacing as soon as the ground thaws in the spring.

(e) Weeding

Assess plantation annually for weed problems. Carry out chemical weed control if seedlings are suffering from competition. Use one application of a leaf absorbed herbicide such as Vision in late August or September to reduce competition. Continue yearly assessments until the average height is 2 m (6 feet)and use chemical or manual weed control as necessary. Plantation is now "free to grow" to age 30-40 years at which point a merchantable thinning may be required.

2. Mature to Overmature "White Spruce Stands"

White spruce stands begin to show reduced growth and decline between 40-60 years of age. In Nova Scotia, white spruce stands do not usually regenerate naturally to white spruce with either shelterwood cutting or clearcutting. Therefore, clearcutting and planting are usually recommended in mature to overmature white spruce stands, preferably following these five steps to successful plantation establishment.

(a) Develop a plan before harvesting:

Do a pre-harvest stand assessment. Is desirable regeneration present? Occasionally, white spruce stands regenerate to red spruce, balsam fir, white ash, or sugar maple if a seed source is available. If desirable regeneration is present and the area is sufficient, divide the stand into two operating areas - Block 1 and Block 2 - and follow the previous suggestions for budworm damaged stands.

(b) Harvest

Ensure that the favoured method of harvest is organized to make future operations as efficient and effective as possible. Good wood utilization and minimal site damage will help at the site preparation stage, if necessary.

(c) Site Preparation

- For whole-tree harvest, may not be needed

- For conventional harvest, rake slash into corridors or let brush rot for 2-3 years, then crush with roller.

- For high risk of seedling debarking weevils, wait at least two years after harvest before planting.

- If necessary, use one application of Velpar L or Vision herbicide to control competition before planting.

(d) Planting

Order trees in advance. Select the best species to match your site. Choose the appropriate stock type unless land classification indicates otherwise.

(e) Weeding

Follow the 1 (e) suggestions for weeding in budworm damages stands.

Summary and Review

( Figure 13 ) will help you decide which stand establishment practices are best suited for your woodlot.

Forests generally grow slowly. It can take 40-60 years for a tree to mature. Stand establishment and development processes that occur on your woodlot will take time to see and understand. Carefully watch and note the effects of cutting and natural succession. Discuss your own particular situation with forestry personnel. You will begin to understand and apply this knowledge to improve the management of your woodlot.