Module 10B: Introduction to Woodlot - Income Tax and Estate Planning

Forest Industry Sector - Overview

The forest industry is important to Nova Scotia’s economy. It is a large contributor to the Province’s GDP – generating substantial export shipments (over $1.0 billion in good years) as well as employing over 11,000 individuals directly. The majority of forest product exports go to the US, with pulp and paper making the largest contribution.

The forest industry is important to Nova Scotia’s economy. It is a large contributor to the Province’s GDP – generating substantial export shipments (over $1.0 billion in good years) as well as employing over 11,000 individuals directly. The majority of forest product exports go to the US, with pulp and paper making the largest contribution.

In Nova Scotia, approximately 70% of the forest land base is privately owned. Consequently, the majority of the fiber used by the forest industry sector comes from private land.

As demand grows for sustainably managed wood, private forest land owners will continue to play an important role in the Province’s economy.

Lesson One - Woodlot and Income Classification

The purpose of this guide is to outline and discuss the main income tax rules and business issues that apply to woodlot operations in Nova Scotia. It is not intended to be a comprehensive tax guide. Other taxes (e.g. GST/HST, property, deed transfer, etc.) are outside the scope of this guide and will not be dealt with. A glossary of terms is provided at the end of the module.

In this guide, the word “woodlot” is used in a broad sense to mean land covered with trees. A woodlot includes treed land held primarily as a source of fuel, posts, logs or trees, whether the trees are grown with or without human intervention. The term also includes treed land that is part of a cottage property and a farmer’s wooded land.

Income tax rules and tax planning opportunities with respect to woodlots are complex. Of necessity, this guide will discuss issues from a broad perspective only. It will not attempt to investigate all the traps and pitfalls of the increasingly technical legislation. In the application of the following discussion to a particular situation, competent professional assistance is highly recommended.

Nature of Business

Commercial vs. Non-Commercial Woodlot

Where a taxpayer acquires a woodlot with intention to sell or resell the wood and operates a woodlot as a business with a reasonable expectation of profit, it is called a commercial woodlot. A woodlot that is not operated by a taxpayer as a commercial woodlot is referred to as a non-commercial woodlot.

The determination between commercial and non-commercial is extremely important, as it is used to determine how your revenue is taxed by Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), which will be discussed in more detail under Business Income and Capital Gains. See Appendix 1 for a decision tree on nature of business and income.

Reasonable Expectation of Profit

You can only determine whether or not a woodlot owner reasonably expects to profit from the woodlot by looking at the facts. You should ask yourself the following questions:

- Do I have a forestry management plan? Is it comprehensive? Am I implementing it?

- How much time do I spend on the woodlot operation compared to time spent on other income earning activities?

- How big is the woodlot? (It may be too small to give a reasonable expectation of profit).

- Do I qualify for some type of government assistance?

- What annual revenue, profits, or losses has the woodlot made in the past?

- What are my farming or forestry qualifications (education and experience)?

- Do I belong to an association of woodlot owners or other relevant professional business organizations?

No single factor will determine if your woodlot has a reasonable expectation of profit. Some factors may be more important than others, depending on the circumstances. For a woodlot operation to have a “reasonable expectation of profit”, a taxpayer should be able to show that with experience, time spent on training, skills, plans and financing, the operation will be profitable over the long run. It is not sufficient to purchase or own a property and hope that it will yield a profit.

Mixed-use Woodlots

A mixed-use woodlot is one where part of the property is personal (non-commercial) and part is business (commercial). Canada Revenue Agency determines what the principal use of the property is. If greater than 50 percent is used personally, it is considered a non-commercial woodlot, and, if greater than 50 percent is business, then it is a commercial woodlot. This is done on a deed-by-deed basis therefore, if the property consists of several separate deeds, each one is considered independently.

Is my Commercial Woodlot a Farm Business?

The Income Tax Act defines farming as:

“tillage of the soil, livestock raising or exhibiting, maintaining of horses for racing, raising of poultry, fur farming, dairy farming, fruit growing and the keeping of bees, but does not include an office or employment under a person engaged in the business of farming”

Note that this list is not exhaustive and it has been determined by the courts that the word farming can include growing trees. The Canada Revenue Agency takes this view: if the main focus of the woodlot business is not lumbering or logging, but is planting, nurturing and harvesting trees under a forestry management or other similar resource plan, and significant attention is paid to managing the growth, health, quality and composition of the stands, it is generally considered a farming business (a commercial farm woodlot). Under these circumstances, reforesting an area of land to produce mature trees at a date that may be 40 to 50 years in the future would be considered farming.

Reforesting is usually a combination of planting and naturally seeded regeneration. Naturally seeded regeneration by itself would not amount to a farming business.

If the main focus of a business is logging (a commercial non-farm woodlot) - not growing, nurturing and harvesting trees - carrying out reforestation activities would not transform that business into a farming operation.

A woodlot owner who grows evergreens to sell as Christmas trees is regarded as being in the farming business regardless of whether he is carrying on any other type of farming operation - provided the operations are carried on with a reasonable expectation of profit.

Where a “traditional” farmer is also a woodlot owner, the Canada Revenue Agency generally considers income from the woodlot to be income from farming.

In practice, it is easier for a corporate taxpayer to carry on a reforestation, cultivating, and harvesting operation as a farming business. The indefinite life of a corporation lends itself to the long business cycle of a tree farming operation.

Contractors and Loggers

There is a class of woodlot owners who purchase cutting rights or forested land for the purpose of harvesting and marketing the wood product. Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) considers these taxpayers to be carrying on a logging business rather than farming. While this appears generally to be the case if purchases are of mature forests only, it does seem debatable where immature woodland is being cultivated to maturity. As discussed above, where a taxpayer relies on naturally seeded regeneration, whether or not the business is a farming business depends upon the focus of the business and how the trees are nurtured.

Exercise 1

Jennifer has a management plan for her 115 acre woodlot. Since she does not live near her woodlot she hires a qualified contractor to manage it for her. The contractor looks after all the operations including harvesting, planting, thinning etc. according to the management plan. Does Jennifer’s woodlot qualify as a commercial farm business? (see exercise 1 for answer)

Business Income and Capital Gains

Business Income

Commercial

Income from a business has always been taxed differently than capital gains. Business income is fully included in income, but capital gains income is given preferential tax treatment. If the woodlot owner has a commercial woodlot (for example, actively cuts and sells the wood product with a reasonable expectation of profit) it seems clear that he/she is in business, and revenues received are included in computing business profits.

Capital Gains

Non-Commercial

On a non-commercial woodlot, where harvesting wood is not part of the taxpayer’s principal business activities, and money or other valuable consideration is received for the sale of timber or the right to cut timber, the sale proceeds are subject to tax on capital account. Generally they are taxed as a disposition of “personal use property.” A loss on the sale of personal use property is not usually deductible. Where the proceeds from a sale of timber exceed the greater of $1,000 and the adjusted cost base of the wood, the sale may result in a capital gain.3 See Appendix 1 for decision tree on nature of business and income.

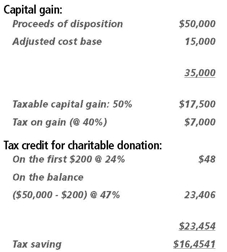

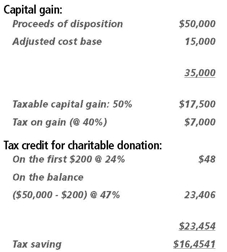

A capital gain is calculated by deducting the adjusted cost base of the wood sold from the proceeds of sale, less any costs of disposition. If only a portion of the woodlot is cut, the adjusted cost base relating to the sale is calculated as the percentage of wood cut over the total wood volume multiplied by the total cost (not including the residual value of the bare land). For example, let’s say a 50 acre woodlot was purchased in 1990 for $25,000 and the value of the bare land was $5,000. If only 10 acres were cut the adjusted cost base would be calculated as follows:

|

10 acres / 50 acres x ($25,000 - $5,000) |

|

|

= 0.2 x $20,000 |

|

|

= $4,000 |

The portion of the capital gain that is taxable depends on the date that the sale is made. Since October 17, 2000, only half (50 percent) of the capital gain is included in taxable income.

You should note that if a taxpayer has merely owned a woodlot without being in business, gearing up to start a commercial business and harvest the wood may result in a deemed (assumed) sale and repurchase of the property at fair market value. We will discuss this in more detail later under the heading “change-of-use.”

"Adventure in the Nature of Trade"

A sale of timber that is an “adventure in the nature of trade” is considered to be business income. The main consideration in determining whether a sale of timber is an “adventure in the nature of trade” is whether the taxpayer’s actions were essentially what would be expected of a dealer in the same property.

Payments Based on Production or Use

Where a woodlot owner allows a person to cut and take timber and the payment is based on the volume of timber taken, the payment is normally taxable as business income. However, based on precedent from a court case, the one-time removal of all of the timber from agricultural property with a fixed price per cord or ton may be taxed as a capital gain.

If a contract fixes the price for the entire cut on a per hectare basis (instead of volume harvested), then the payment may be considered capital even though payments may be made periodically during the cutting.

Where a contract calls for a fixed price which cannot be varied in any event, but the timing of instalments of that fixed price is to vary depending on production or use, then a capital gain will result.

When is Income Reported?

For a commercial woodlot, Canada Revenue Agency requires the income to be reported when earned. This is the year in which the wood is cut and shipped, which is not necessarily when the cash is actually received. If it is a non-commercial woodlot, income is included based on the date of the sale agreement. If part of the proceeds is not due until a subsequent year, the capital gain in respect of the portion of the proceeds not received can be deferred until the taxation year in which they are due. A minimum of 20 percent of the gain must be included in income each year; therefore, it is possible to spread the inclusion of the capital gain over a maximum of five years. Note that taxpayers generally will try to spread over two years, as most do not want to wait five years for the full proceeds.

Who Reports the Income?

For tax purposes, the business income or capital gain must be included in the income of the beneficial owner of the standing timber. The deed to the property may only be in one name, but this does not necessarily mean that beneficial ownership fully rests in that person. Similarly, property might be in the name of two or more persons but this does not signify that all individuals have beneficial ownership. For example, two names could have been added to the deed for purpose of probate, but this may not result in the transfer or acquisition of beneficial ownership. If there is a change in beneficial ownership of the property, there is an assumed disposition, and this might result in a tax liability.

The rest of Part One of this guide will be devoted mainly to those taxpayers who own and operate a woodlot as part of their ongoing business activities (commercial woodlot).

Business Losses

When computing your business income, you are only allowed to deduct expenses that were incurred for the purpose of gaining or producing income from the business.4 This provision of the Income Tax Act operates nicely when profits are being earned, but leads to uncertainty when losses are incurred.

If losses continue for several years it becomes more and more important that you can demonstrate a “reasonable expectation of profit” (supported by financial projections and other evidence), as the Canada Revenue Agency is more likely to challenge you with each year that passes. If you cannot demonstrate a “reasonable expectation of profit,” the expenses/losses (net of revenues) are considered to be personal in nature and cannot be deducted against other sources of income.

Types of expenses that can be deducted from business income are discussed in Part one, Lesson 3.

Exercise 2

Denis purchased a woodlot for $25,000. It was determined that the bare land value was $10,000. Denis later decided to harvest all of the wood and received proceeds of $60,000 for the wood (he kept the land). Professional fees on the sale of the wood were $1,700. Calculate the capital gain. (see exercise 2 for answer)

Module 10b - Lesson One Quiz

| Questions: | 12 |

| Attempts allowed: | Unlimited |

| Available: | Always |

| Pass rate: | 75 % |

| Backwards navigation: | Allowed |

Lesson Two - Business Types

Business Entities

The three most common types of business structures (sometimes called business entities) are proprietorships, partnerships, and corporations. Each of these has unique legal and income tax features.

Proprietorship

A proprietorship is a business carried on by an individual. The individual is the owner, in charge of and ultimately responsible for all activities of the business. The owner assumes all the risks and does not share the profits or losses. Profits are calculated after deducting reasonable expenses. There is no legal difference between the individual and the proprietorship. If the business fails, the individual’s personal assets may be subject to seizure by creditors.

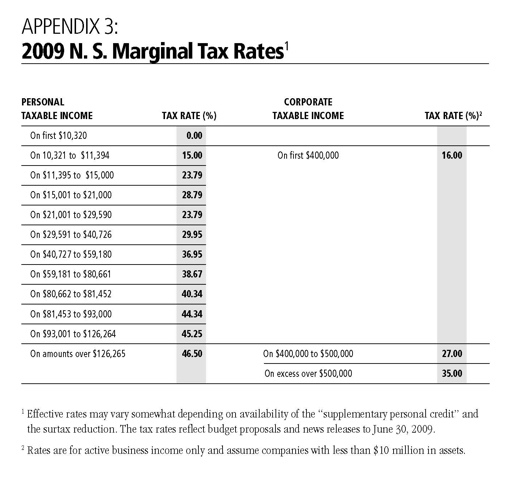

For income tax purposes, the business income and losses get added to the individual’s income from other sources. The proprietor is taxed on the net income, not based on cash drawings from the bank account. Tax is calculated on taxable income at graduated personal income tax rates.

Lumping income and losses from different sources together allows the individual to deduct losses against other forms of income, such as employment or investment income. This may be a big advantage during a business start-up period, when there are often losses.

If business losses exceed income from all other sources in a particular year, the excess may be carried back to recover tax previously paid or carried forward to reduce future taxable income. See Appendix 2 for details on the allowable carry-over period.

You should note that use of the word loss or losses refers to the situation where deductible expenses exceed revenues. It does not necessarily include the situation where a woodlot owner suffers an economic loss due to a natural event such as fire, hurricane or insect damage. Under these circumstances, the taxpayer might be entitled to a write-off only if there are previously undeducted costs associated with the woodlot. Such a write-off would not be available for any costs attributed to the underlying land.

When the owner sells or otherwise disposes of the business assets – for example, by transfer to family member, deemed disposition on change-of-use from business to personal use, or deemed disposition on death; then business income or losses may result as well as capital gains or losses.

Partnership

A partnership is an agreement between two or more parties to combine resources, credit, and expertise to carry on business together in order to earn a profit. Although the partnership possesses assets and property of its own, it is not a separate legal entity from the partners. Each partner is fully responsible for the debts and business obligations of the partnership. If the business fails, each partner’s personal assets may be subject to seizure. Although a written contract is not necessary, a signed partnership agreement is highly recommended. This agreement should set out the rights and obligations of the individual partners, including but not limited to:

- income sharing entitlements

- financing or capital requirements

- property to be contributed

- personal involvement requirements

- admission and departure of partners

- dissolution of partnership

A partner who contributes a particular asset to a partnership would not necessarily receive the asset back if the partnership is dissolved unless it is written into the partnership agreement or otherwise agreed to by the partners.

For income tax purposes, the partnership calculates its taxable income and allocates this amount among the partners. A partnership does not file its own income tax returns. Each partner includes his share of income or loss on his personal income tax return. (Again, the amount of cash drawn from the partnership’s bank account by a partner does not factor into the partner’s income.) The result is the same as if each partner were a proprietor who had earned that much income or suffered that much loss. The loss carryforward and carryback rules are the same as for a proprietorship.

An interest in a partnership is a capital property that can be sold or transferred to another person, subject to terms or conditions in a partnership agreement. Any gain or loss on the sale of a partnership interest would be a capital gain or loss. The cost of a partnership interest is increased by the partner’s share of earnings and reduced by the partner’s share of withdrawals or distributions from the partnership.

On wind-up, a partnership generally disposes of all of its assets to its partners at fair market value. Business income and capital gains would be allocated to the partners. However, a rollover is available on the wind-up of a partnership where each partner receives a pro-rata undivided interest in each property of the partnership. The benefit of this rollover provision is that inherent gains in the partnership property are not taxed until some time in the future. The drawback is that the partners must hold the property (distributed on wind-up) jointly. If this is impractical for some assets, they may be distributed to particular partners before the wind-up. A similar type of rollover is available where one partner buys out the other partners and carries on the business as a proprietorship.

Corporation

A corporation is a separate legal entity, distinct from its shareholders. It may own assets and incur debts and can generally contract and negotiate on its own behalf. Shareholders are not responsible for the debts of the company unless they have provided personal guarantees. Private companies are usually set up under the laws of a province, although federal incorporation is available. The incorporating statute will impose some formalities on the company, such as the need to hold meetings, elect directors and officers, and so on.

For tax purposes, a corporation calculates its own taxable income and files its own tax return. You can see from Appendix 3, a company in Nova Scotia pays tax at a favourable provincial rate on its first $400,000 and a favourable federal rate on its first $500,000 of business income earned in a particular fiscal year. If the business is profitable and generates more income than the shareholders need for personal living requirements, this difference in tax rates is a big advantage to incorporation. The tax savings provide additional funds to finance growth or reduce debt. However, this difference in taxes is actually a deferral of tax. There is a second level of taxation when the retained earnings of the company are eventually distributed to the shareholders. Nevertheless, this tax bill may be postponed indefinitely, as long as the profits stay in the corporation.

The shares of certain qualifying corporations are eligible for a $750,000 capital gains deduction on their disposition. There are tests to be met, but as long as substantially all of the company’s assets are used in the business, the shares should qualify. Other assets, such as excess cash, stock market investments, or rental properties, may create problems. The problems may be avoided with advance planning and preparation, so that the shares of many private companies will qualify. On the other hand, if the business is carried on as a proprietorship or a partnership, only capital gains on qualifying farm land, farm buildings, farm quota, and interests in family farm partnerships are eligible for the $750,000 capital gains deduction. So if the business is not farming, the $750,000 capital gains deduction can only be achieved if it is carried on through a corporation.

One disadvantage of incorporation is that if there are losses in the early years of a business, there is often no other source of income in the company against which they can be claimed. Otherwise, the loss carryover rules for corporations work exactly the same as for proprietorships and partnerships.

On the wind-up of the business and distribution of the assets to the individual shareholders, the company is taxed based on dispositions of assets at market value. Shareholders will also be taxed on the amount of taxable dividends they are considered to receive. This ends the tax deferral advantage of incorporation we mentioned earlier, which is why corporations often carry on as personal holding or investment companies after the business activities have been wound down.

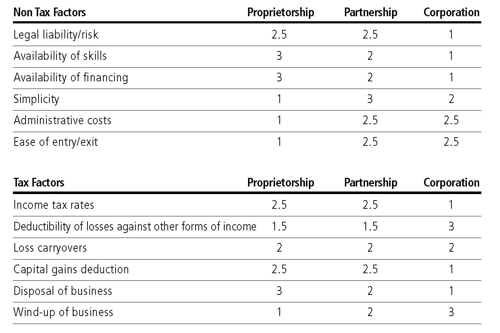

Choosing the right business entity

Choosing the right business entity will always depend on the particular circumstances of the business. Limited legal liability and lower income tax rates available through a corporation are often deciding factors, but these are offset somewhat by higher cost of administration and complexity.

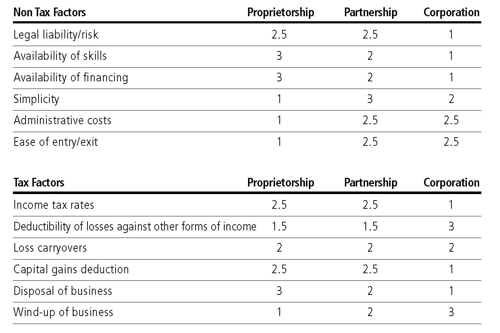

The table compares the tax and non-tax factors that should help you choose a business entity. A score of one shows the advantage lies with that choice of entity. A score of three shows a disadvantage for that entity. If there is no significant difference between two or more entities, their scores have been averaged. We have tried to rank the factors in decreasing order of importance. However, the scores and the rank are subjective judgements, meant to serve as a guideline only.

Change from one business structure to another

You can generally start a business operation as a proprietorship and transfer the business assets to a partnership or a corporation at a later time without immediate tax consequences. Usually, you can also incorporate a partnership without tax consequence or, as mentioned before, one partner can usually acquire the other partners’ interests in the partnership and carry on the business as a proprietor without tax consequence to the continuing partner.

There are no provisions in the Income Tax Act however, for the transfer of business assets of a company out to individual shareholders so that the business can be carried on as a proprietorship or partnership. Such a transfer can rarely be made without tax. Transfers of business assets between companies can often be achieved without income tax effect.

Although switching between business entities is often feasible, it is certainly a complex area from an income tax point of view. There are many technical traps to avoid and many planning opportunities that should be considered, such as estate planning, income splitting, creditor protection, and so on. Remember that the purpose of “switching” is to achieve long-term advantages. Up-front costs should be evaluated like any investment undertaken by the business. Professional assistance is a must.

Ranking of business entities based on tax and non tax factors. (Actual Nova Scotia Marginal 2009 tax rates are found in Appendix 3.) A lower score implies an advantage lies with that business entity for that particular tax or non-tax factor. A higher score implies a relative disadvantage. If there is no significant difference, scores have been averaged.

The above tables are meant to assist a woodlot owner in reflecting on factors that are most relevant to their situation. The rankings are subjective and may change based on individual circumstances.

Special Farm Rules

There are several special income tax provisions that are applicable to farmers.

Cash Basis Accounting

Non-farm business income is normally measured using the accrual basis of accounting, however farmers can choose to report on the cash basis.

Once you choose to file your tax return using the cash basis, you can only switch to the accrual basis of accounting with the approval of CRA.

If you use the cash basis, you only use revenues for which the cash has actually been received, and expenses actually paid in the year to determine income. This lets the taxpayer reduce income by paying off outstanding bills at year-end.

Cash basis farmers do have the option of adding an amount to their income up to the fair market value of their inventory. This allows them to smooth or average income. Using these provisions they can avoid the possibility of not paying any tax in one year, and missing the advantage of the low marginal rates, followed by a year of high taxable income, some of which is subject to the top marginal rates. The provision may also be used to increase income and take advantage of old losses that might otherwise expire.

Loss Carryovers

See Appendix 2 for loss carryovers allowed for farming losses.

Restricted Farm Losses

A business carried on with a “reasonable expectation of profit” may have losses. But where “a taxpayer’s chief source of income for a taxation year is neither farming nor a combination of farming and some other source of income,”5 the loss from farming that can be used as a deduction against income from other sources is limited to the first $2,500 of loss plus one-half of the next $12,500 for a maximum of $8,750. Any excess (known as a “restricted farm loss”) can be carried back or forward as shown in Appendix 2. Restricted farm losses can only be used to the extent of farm income in those years. In this way, the benefits from tax losses which often arise in the early years of business - and are accelerated by use of the cash method of accounting - are restricted for part-time farmers when farming if farming is not their main course of income. This is also true for an individual who combines farming with another source of income. See Appendix 1 for summary.

Whether or not farming is the taxpayers primary source of income has been the subject of endless court cases. The courts have considered time commitment, capital commitment, and expectation of profitability to be determining factors.

You need to ask:

- How much time is spent farming versus generating income from other sources?

- How much capital is invested?

- What is the gross revenue of the farming operation?

- How much farming experience and knowledge does the taxpayer have?

- What is the income potential of the farming business (as demonstrated by a business plan)?

You should note that for a hobby farm with no expectation of profit, no expenses are deductible on your tax return.

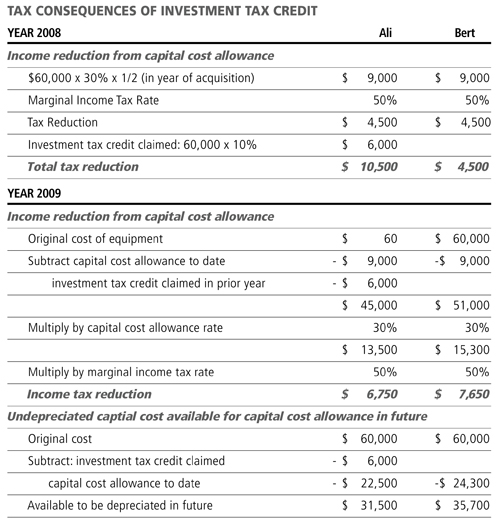

Investment Tax Credits

Investment tax credits are available to farmers and loggers in Nova Scotia for expenditures on “qualified property.” An eligible expenditure must be for a qualifying building or qualifying machinery and equipment. The asset must be new and unused at the time of purchase. Property that has been previously owned, used as a demonstrator, or leased is not eligible. The asset must be acquired to be used by the taxpayer in Canada primarily (more than 50 percent) in the taxpayer’s business of farming or logging. (Use in other industries may also qualify but that is outside the scope of this booklet.) Examples of buildings, machinery and equipment that qualify include nearly all structures, machinery and equipment used in farming or logging activities, except for cars and trucks designed for use on highways. However, logging trucks weighing more than 7,258 kilograms will qualify.

The available credit is calculated at 10 percent of the capital cost of eligible assets. The credit must be claimed within 18 months of the tax year end or it is lost.

Capital cost is the actual cost less any other government or non-government assistance received. HST recovered as an “input tax credit” is not included. The credits are available to all taxpayers regardless of size or legal structure of the business, and can be used to offset 100 percent of federal income taxes payable. If not enough federal taxes are payable against which to claim the investment tax credits, 40 percent of current year credits earned by individuals and certain corporations are refundable. A corporation will not qualify for this refund if it had - or was part of an associated group of companies that had - taxable income of more than $500,000 in the immediately preceding taxation year for years beginning after 2008 ($400,000 for 2008, $300,000 for years between 2003 and 2007). Further restrictions to the refund apply to companies (or groups of companies) with more than $10 million in assets.

Investment tax credits earned but not used to offset federal taxes payable or refunded to the taxpayer can be carried back three years and forward twenty years (for tax years after 2006, carried forward 10 years for years before 2006) and claimed against federal taxes in those years.

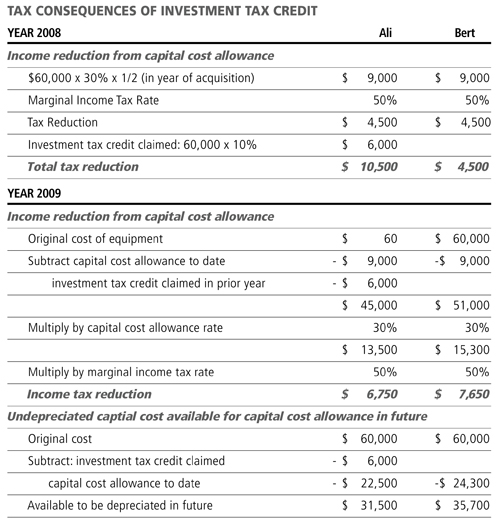

Here is an example that shows the benefit of investment tax credits. Let’s assume the following:

-

Two individuals, Ali and Bert, each acquire a piece of equipment for $60,000 in 2008. Ali uses the equipment in logging (an eligible activity for investment tax credit purposes) whereas Bert uses the equipment in an ineligible activity (perhaps construction).

-

In both cases the equipment can be depreciated at a rate of 30 percent for income tax purposes.

-

Both individuals are earning profits and have a marginal tax rate of 48 percent.

The tax consequences are shown in the table below. You will see that claiming an investment tax credit will result in lower capital cost allowance claims in following years.

Capital Gains/Succession

In many cases, farmers receive favourable treatment on the taxation of capital gains. There are also rollover provisions for the tax-free transfer of a farming business from parent to child. We will also discuss these in more detail later.

Exercise 3

Justin has just inherited a woodlot. He decides to supplement his income from a local garage with income from the woodlot. He has decided to purchase a small tractor to use with a trailer to haul wood. In the first year of business, he spends $20,000 on a used tractor and his other costs total $7,000. His loss in the first year is $10,000 (tractor depreciation plus other costs). How much of this is he entitled to claim against his income? (see exercise 3 for answer)

Exercise 4

Raymond purchased a new skidder in 2008 at a cost of $36,000. The skidder is used in a farming business and can be depreciated at a 20% rate. Raymond has a marginal tax rate of 30%. What would his income tax reduction be for the year 2008? (see exercise 4 for answer)

Module 10b - Lesson Two Quiz

| Questions: | 10 |

| Attempts allowed: | Unlimited |

| Available: | Always |

| Pass rate: | 75 % |

| Backwards navigation: | Allowed |

Lesson Three - Measuring Income

Record Keeping

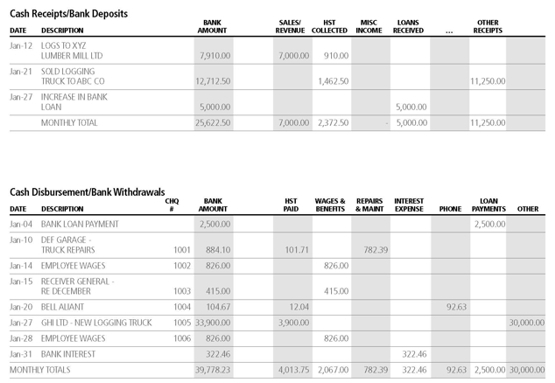

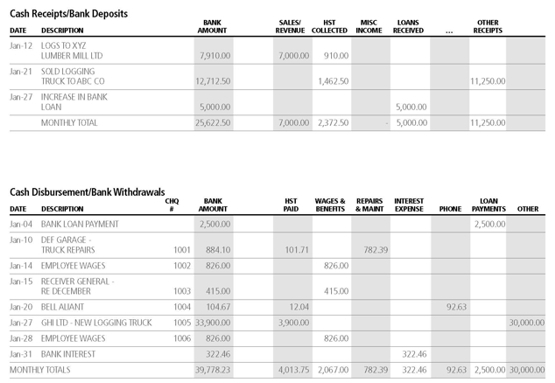

Anyone carrying on a business is required by law to maintain books and records so that they can determine income and what taxes they must pay. They must also keep records documenting the calculation of payroll taxes, HST, workers’ compensation, and so on. Keeping books and records generally centres on the bank account. As a rule, corporations and partnerships have a separate bank account through which the business transaction would flow. Although not legally necessary, record keeping for a proprietorship is much simpler if a separate bank account is kept for business transactions.

Record keeping systems are available to suit all levels of complexity. Generally they are designed to document and summarize revenue and expense transactions, and to keep a financial record of investments in assets and business liabilities.

Electronic record keeping through an off-the-shelf package is most common and not difficult to learn if you have basic computer skills. It is less prone to error and simplifies the record keeping process.

A basic manual record-keeping journal is shown in Appendix 4. You enter financial details of business transactions in a multi-column journal, often called a cashbook, as the cash is received or disbursed. You keep separate columns or accounts for each category of receipt or disbursement that is regular or large. This makes it easy to summarize accounts and prepare financial statements from time to time. Cashbooks are available with many columns and, if necessary, the receipt and disbursement transactions may be kept in separate journals.

In this basic manual system, you would keep an “open item file” for accounts receivable invoices and a separate one for accounts payable invoices. When preparing financial statements, you would take listings for businesses using the accrual basis and make appropriate adjustments for these unrecorded invoices. Other adjustments would also be made for unpaid wages and other liabilities as well as inventory levels.

A new cashbook should be used for each fiscal period. It should be totalled and balanced from time to time - preferably monthly - and ideally posted to a general ledger, which keeps a more permanent record of the business accounts. Regardless of the size of the business, it is important to compare and reconcile the transactions in the cashbook with those on the business bank statements. As business activity grows, you can upgrade to a more sophisticated manual record keeping system. However, a computer system will probably be the practical solution over the longer term.

Although a basic cashbook and general ledger work well to document and summarize transactions, you must also keep the supporting documents themselves - contracts, expense invoices, revenue invoices, deposit slips, bank statements and cancelled cheques, etc.

Canada Revenue Agency Requirements

The Canada Revenue Agency will allow the following methods of record keeping: - books, records, and supporting documentation prepared and kept in paper format

- books, records, and supporting documents prepared on paper, and later changed to and stored in an electronically accessible and readable format, such as a PDF file

- electronic records and supporting documents prepared and kept in an electronically accessible and readable format.

CRA does not specifically tell you what needs to be kept, but your records have to be reliable and complete, provide the appropriate information needed to determine your tax obligation, be backed up by original documents for verification of transactions, and include additional documents that help to determine tax obligations, such as appointment books, mileage logs, GST/HST returns, and so on. In addition to this, if your business is incorporated CRA requires you to keep any minutes of meetings held, record of a corporation that includes information relating to ownership of shares, general ledgers that summarize the transactions of each year, and special agreements needed to back up the entries in the general ledger if they are difficult to understand.

Per CRA, the general rule is to keep all records and supporting documentation, whether in paper or electronic format, for a period of six years from the date CRA assesses your tax return. You should note that if you use computerized systems to generate records, you must keep the electronic records, even when a hard copy is kept. Documents dealing with items of a long-term nature that would affect eventual sale or wind-up of business should be kept indefinitely. Examples would be loan documents, equipment purchases, share registry etc.

Accounting documents may be destroyed earlier if you have received permission from the CRA in writing. Even then, be cautious, as CRA’s blessing will not influence other government agencies such as workers’ compensation authorities.

The records and books of account must be located at the place of business or at another place designated by the Minister of Finance and must be made available at all times to officers of the Minister for audit purposes. Penalties may be imposed by CRA if adequate records are not kept, you do not give officials access to your books when requested, or you do not provide information to officials when asked. In addition expenses may be disallowed if you cannot provide supporting source documents. These fines can be large and therefore it is advisable to keep well-organized records.

Receipts/Revenues

Businesses normally generate their cash flow from one or two main sources, so the variety of cash receipts that a business must account for may be small. It is often helpful when managing a business to have a more detailed breakdown of these revenue sources, but there is no requirement to do so. A woodlot operator may want to track revenue from hardwood and softwood sales separately, for instance, or keep cedar and spruce sales separate, or track revenue from one woodlot separately from another.

If you need such a detailed breakdown, it can easily be handled with the record keeping system outlined above by adding the appropriate columns to the cashbook. Nevertheless, most cash receipts could be accounted for under the following headings:

- sales revenue/collection on account

- HST collected

- miscellaneous income

- loans received

- other receipts (e.g. equipment sales or trade-ins, advances from shareholders, HST refunds, income tax refunds, and so on)

- Sales revenues, sundry income and equipment sales are all relevant in determining taxable income.

Expenses

For a woodlot operation not carried on as a farming business, income must be reported using the accrual method. Generally speaking, expenses directly related to the commercial activity are deductible in the year incurred.

Capital costs

Payments on capital assets cannot immediately be deducted for income tax purposes. This is true regardless of whether the taxpayer calculates income using the cash basis or the accrual basis of accounting. Capital assets tend to be of a long-term nature and provide an enduring benefit. Examples include land, buildings, automotive and other equipment (such as motor vehicles, tractors, chainsaws, winching equipment, skidders, etc.), fencing, timberland, etc. Generally, equipment or tools that will be of use for more than one year are considered capital assets and are depreciated over the long term for income tax purposes.

For practical purposes, an immediate write-off is allowed for a tool costing less than $300. Note that an item that may appear by itself to be a capital item may be deductible as a repair if it is in fact a replacement part or component for a larger piece of machinery. Inventory (such as seedlings and plantations, see below) is not considered a capital asset and neither is the cost of supplies that are consumed in the business.

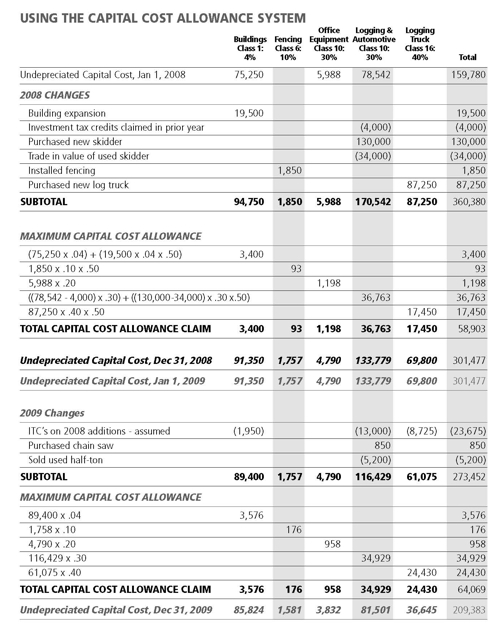

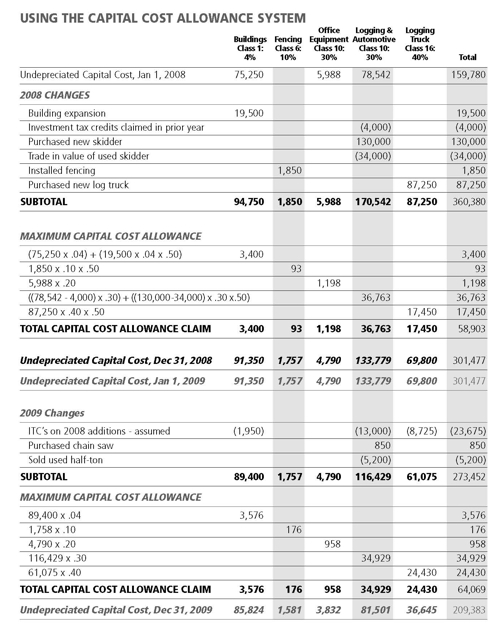

For income tax purposes, depreciable capital assets are grouped into classes. Capital cost allowance (depreciation) is then calculated at prescribed rates on a declining balance basis. Only one-half of the normal capital cost allowance rate is used on the net additions to a class for any particular year. Net additions are determined by subtracting from the cost of new assets the proceeds of disposal, up to the original cost, of any assets of the same class that were traded-in or otherwise disposed of during the year. The table on the next page shows the use of the capital cost allowance system.

You should note that if all assets in a class have been disposed of, any remaining balance may be written off. This is referred to as a terminal loss. On the other hand, if the proceeds from the disposal of assets result in a negative balance in the class, this amount gets included in income as recaptured depreciation.

Depletion

Canada Revenue Agency refers to woodlots as “timber limits,” in other words a treed area of land. The cost of a “timber limit” includes the cost of the underlying land and may also include the cost of surveys, cruises, maps, and so on. The total cost - less the residual value of the land and the cost of surveys, cruises, maps, etc. - is depleted when trees are harvested. A deduction for depletion, based on quantity harvested, is calculated by multiplying this “net cost” of the timber by the quantity of wood harvested and dividing by the quantity of timber in the limit as shown by a cruise. A further deduction – equal to one-tenth of the cost of surveys, cruises, maps and so on - is allowed until their cost has been fully deducted.

For example, let’s assume a woodlot owner is beginning to harvest a timber limit. The owner’s cost of the timber limit is $55,000 of which $8,500 is applicable to the residual value of the land. In addition, $5,000 has been incurred for cruises, surveys, etc. The cruise indicated there were 2,500 cords of timber in the limit of which 625 were harvested during the year. In the example below we show how to calculate the deduction for depletion of the timber limit.

Basic deduction:

= (Cords harvested / Cords documented by cruise) X (cost of timber limit less residual value of land)

= (625/2500) X ($55,000 - $8,500)

= $11,625

Additional deduction re: cost of cruises, surveys, etc.

= Total cost thereof X 1/10

= $5,000 x 0.1

= $500

Total depletion deduction for the year is $12,125.

Exercise 5

In 2007, Ian purchased 150 acres of land for $45,000. The bare land value of the land is $15,000. Prior to purchasing, he had the woodlot cruised, which indicated that the woodlot contained 2,400 cords of wood. In 2008 he purchased a used ATV for $9,000 and a used wood splitter for $2,000. In the fall he cut and sold 18 cords of stud wood and 6 cords of firewood.

A) Assuming a capital cost allowance of 30% for the ATV and 20% for the wood splitter and that he bought the ATV for 75% business use and 25% personal use, what deduction can he make for his equipment purchases in 2008?

B) How much can he claim for depletion of the land?

(see exercise 5 for answer)

There is an alternative method of claiming depletion for a timber limit in which the lesser of $100 and the amount received in the year for the sale of timber is allowed as a deduction. This method obviously has limited application and benefit, but may apply where the timber resources have not been documented by a cruise.

Inventory

The cost of seedlings and planting represent the cost of inventory for tree farmers, and, for cash basis taxpayers, these costs would be deductible as paid. The CRA’s position appears to be that these costs do not represent “purchased inventory” subject to the mandatory inventory adjustment. This means that even if there is a loss in the year, the cost of seedlings and planting do not need to be added back. Remember, however, that cash basis farmers can also smooth or average their income by adding to income an amount up to the fair market value of their inventory. For accrual basis taxpayers, these costs would be carried forward and deducted against future revenue. Harvesting costs (including depletion of timber limits for non-farmers) would be treated the same way. If the taxpayer operates woodlots but generally not as a farmer, the costs of seedlings and planting would become part of the cost of the timber limit.

Maintenance and operating costs

Annual maintenance costs such as thinning and spraying should be fully deductible as incurred or as paid, depending on which accounting method you use. Other costs such as labour, equipment operating and maintenance costs, property taxes, office supplies, and marketing expenses would also be deducted as incurred or as paid.

Vehicles – what can I deduct?

Vehicle operating costs incurred for earning income can also be deducted to determine your net income. Some of these costs include, lease payments, interest on loan to purchase car, repairs, insurance, fuel and so on. Again, depending on which method of accounting is used, they are either deducted when they are paid or become payable.

The rules for the deductibility of vehicle expenses differ whether the business is operated as a proprietorship or a corporation and whether the corporation owns the car or the individual does.

In a proprietorship, if the vehicle is also being used for personal purposes, appropriate adjustments should be made to the expenses claimed by the owner. Total expenses would be prorated between business versus personal use, based on a mileage log.

If vehicles used personally are owned by a corporation, taxable benefits will be assessed for personal use. On the other hand, if vehicles are personally owned and used in the corporation, the corporation can pay out a tax- free allowance on a reasonable per kilometre basis to reimburse you for business kilometres. The mileage allowance is deductible to the company and is deemed to include HST. There are various restrictions on the expenses that can be claimed based on the type of vehicle and its business versus personal use. You should consult your accountant to discuss and advise you in this area.

Interest and taxes

Interest and property taxes are deductible expenses provided they are incurred to earn income from a business or property. Although there may not be revenue in a given year, if a woodlot is held mainly with the intent to produce income, then interest and property taxes should be deductible.

Module 10b - Lesson Three Quiz

| Questions: | 10 |

| Attempts allowed: | Unlimited |

| Available: | Always |

| Pass rate: | 75 % |

| Backwards navigation: | Allowed |

Lesson Four - Miscellaneous Matters

Change-Of-Use

As we mentioned before, a taxpayer who has owned a woodlot without being in business and decides to harvest the wood through a commercial operation themselves may have a deemed (assumed) sale and repurchase of the woodlot at fair market value. This “change-of-use” and the income tax rules associated with it depend on changes in the taxpayers’ intentions and/or activities with respect to the property.

The gain resulting from the deemed sale on the property changing from personal use to business use would be a capital gain. The taxpayer then has an increased cost base in the property that should be eligible for a deduction for depletion, as we discussed earlier for timber limits. However, if the timber is part of a timber limit, the stepped-up cost base is reduced for depletion purposes by the non-taxable portion of the capital gain (now 50 percent) as well as any taxable portion that has been sheltered by the capital gains deduction. Tax deductions are only allowed when expenditures are actually made, or when items included in income actually result in additional tax.

If the change in use were from personal use property to farm inventory, the rules may have different consequences. If the taxpayer is using the cash basis method of accounting, no payment has been made for the cost of the inventory and no deduction would be allowed in computing business income. The end result of such a change-of-use may be a capital gain at the time of the change with no increased deduction against business income as the timber is harvested. You should note that such a change (capital personal use property to farm inventory prior to harvesting) would be very difficult to prove.

Government Grants

The general rule is that all government grants are included in income from a business.9 If the grant relates to the cost of acquiring capital property or an outlay or expense incurred however, the taxpayer may elect to offset the grant against these amounts.

So, for a woodlot owner, a grant received could only be excluded from the calculation of the current year’s income if it was used for the actual purchase or planting of a timber limit (or perhaps the purchase of a piece of machinery) and the taxpayer elects to apply the grant against the cost of the limit (or machinery).

If the grant was received to fund general operations, such as repairs and maintenance, it would either be fully included in income - with any expenses incurred fully deducted - or it would be offset against the expenses with the net expenses being deducted. These alternative methods produce identical results.

Year End

Since 1995, unincorporated businesses (proprietorships and partnerships) have been required to have a calendar year end (December 31) for tax purposes. A corporation may choose any year end, which provides more flexibility. You may want to have a different fiscal year, for instance, if your business is seasonal, choosing a fiscal year end date to coincide with a slack time in your business.

In certain cases, corporate tax may be deferred for the first year of operations by choosing a fiscal year that will postpone the recognition of income to the second year. For example if a business is incorporated in January and income begins to be earned in October, a fiscal year of September 30 could be chosen to obtain a maximum deferral of tax to 15 months after the income is earned.

In certain cases, corporate tax may be deferred for the first year of operations by choosing a fiscal year that will postpone the recognition of income to the second year. For example if a business is incorporated in January and income begins to be earned in October, a fiscal year of September 30 could be chosen to obtain a maximum deferral of tax to 15 months after the income is earned.

Income Splitting

In Canada, family members are mostly taxed independently on their income. This, combined with the graduated personal income tax rates, provides an opportunity and an incentive to reduce income taxes by spreading income among family members. Taxpayers and their advisors have devised various ways of splitting income and the Department of Finance has been busy blocking those methods that they find offensive.

Nevertheless, there are still many valid methods to split income and reduce the family’s total tax bill. For woodlot owners, probably the most relevant way to split income is to pay a reasonable salary or wages to spouses and children. Another is to have family members participate in the ownership of a business carried on through a corporation. Dividends can then be paid to the spouse and children over 18, resulting in lower overall taxes. (This method requires careful planning, as there are pitfalls.)

Other methods, which are not specific to woodlot owners, include pensions splitting for seniors, making spousal RRSP contributions and spending the earnings of the higher income spouse, while the lower income spouse saves and invests. This results in investment income being taxed at a lower rate.

The benefits of income splitting are shown in this example. Let’s assume that an individual operates a woodlot and has a taxable income from it of $60,000. The individual’s spouse works part-time outside the family business and has a taxable income of $15,000. The spouse also participates in the family business by keeping books and financial records, answering phones, delivering messages, doing odd jobs, and generally helping as much as possible. The spouse has not been paid a salary or wage for these services. By paying the spouse a $15,000 salary and reducing the individual’s taxable income by the same amount, the family’s total income is unchanged. But there is a big impact on the family’s income taxes. This impact is shown below.

1. Reduction in individuals income taxes by reduction of taxable income from $60,000 to

$45,000.

$15,000 x 36.951 = $5,543

2. Increase in spouse’s income taxes by increase in

taxable income from $15,000 to $30,000.

$15,000 increase at this level2 = $4,153

Total income tax savings = $5,543 – 4,153

= $1,3903

1. See Appendix 3 for marginal income tax rates

2. Note that there are three tax brackets within this increase, for simplicity we have only shown the final tax result.

3. Note the tax rates only take into account the basic tax credit.

Claw-Back, Etc.

Several federal programs are subject to an income or means test. For instance, individuals over the age of 65 are generally entitled to Old Age Security (OAS). For 2009, this is approximately $517 per month ($6,204 per year). However, as a senior’s income rises above $66,335, the OAS is “clawed-back”.

The amount “clawed-back” is equal to 15 percent of the amount by which the individual’s net income exceeds $66,335. Thus for 2009, an individual’s OAS will be completely repayable (“clawed-back”) when their income reaches $107,695. [($107,695– 66,335) x 15% = $6,204].

The age tax credit of $5,276 available to seniors is also subject to an income test. This credit against federal taxes is reduced as income increases above $31,524. For 2009 the credit is reduced by 15 percent of the amount of net income of more than $31,524, until it is fully eroded. Once an individual’s income level is more than about $66,697 they will no longer be entitled to any age tax credit.

Other federal programs that are influenced by family income levels include the “guaranteed income supplement,” the “family benefit system,” and the “goods and services tax credit.”

Many woodlot owners (particularly those who sell stumpage) do not have a regular income from the woodlot. So, they need to consider how irregular income levels affect the benefits available under these federal programs.

You can use one of two strategies to minimize the effects of these claw-backs. The first is to spread the income over several years to avoid any unnecessary claw-backs altogether. The second is to crowd as much of the income as possible into one or two years so that the benefits will be lost for only a short period of time. When choosing a strategy, you should consider your income from other sources, the corresponding marginal tax rate, and how much income will be made from the woodlot.

Filing your taxes on time

If you operate your woodlot as a sole proprietor or a partnership, the tax return is not due to be filed until June 15th of the following year, but any taxes owing are due by April 30. If your woodlot business is incorporated, you have three months from your year end date to pay any taxes owing and six months to file the corporate tax return.

Interest is charged daily by CRA at prescribed rates for any late payments on income taxes – the rate for the first quarter of 2009 was 6 percent. Interest and penalties paid to CRA are not deductible for tax purposes. If you do not file the return on time, in addition to interest, you will be charged a penalty. The penalty is calculated as 5% of the tax balance owing, plus 1% per month up to a maximum of 12 months. However, note that if you were fined a penalty in any of the last three taxation years, the penalty for the current year would be 10% of the tax balance owing plus 2% for each full month the return is late up to a maximum of 20 months.

Module 10b - Lesson Four Quiz

| Questions: | 10 |

| Attempts allowed: | Unlimited |

| Available: | Always |

| Pass rate: | 75 % |

| Backwards navigation: | Allowed |

Lesson Five - Introduction to Estate Planning

The Need for Estate Planning

This section is intended for people who own woodlots and want to plan for the future. It will help owners develop a clear plan of how to pass the woodlot on to a spouse or a child.

Often people pass away without making plans for the future. This can cause confusion and sometimes legal or other costs at a difficult time for the family. Sometimes it can result in significant taxes being due from the estate that might otherwise be reduced or avoided.

For these reasons, estate planning is essential. We will explain estate planning for woodlot owners in a general way and will not deal with all situations; rather we will only deal with the most common situations and problems that you might encounter. We will outline the background of estate planning and explain terms. We will also discuss various strategies that may reduce taxes on death. Planning now can make your wishes happen when you are gone.

The Estate Planning Team

Estate planning can be complex, and ensuring the plan is properly implemented is crucial to its effectiveness. Assistance of several professionals may be required, including a lawyer, an accountant, a financial planner, and an insurance agent. It is important the individuals that you select have a solid expertise in estate planning. Some questions that you may wish to ask potential advisors would include, but are not limited to:

- Do they have a professional designation or a relevant degree?

- What is their experience – how long have they been practicing estate plans?

- Have they put into practice estate plans with similar complexity to yours?

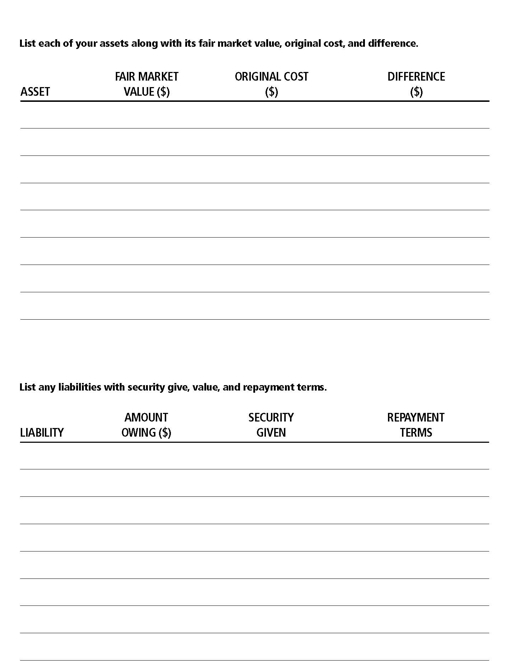

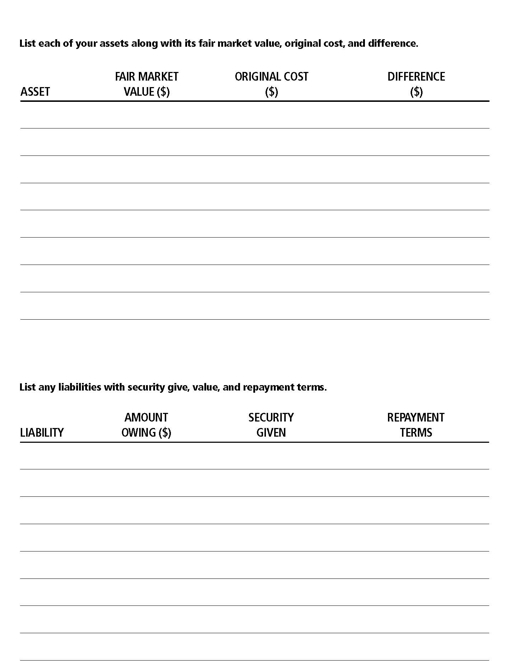

Time and money will be saved if you are able to gather all the necessary materials before you visit an advisor or begin to plan the estate. The following is a list of materials you should have:

- family details: age, marital status, involvement in woodlot or other business interests

- current will if you have one

- list of assets: cost, (V-day value if applicable), and market value

- any appraisals or other valuation information

- list of liabilities: amounts, security given, and repayment terms

- details of form of ownership of assets: personal, corporate, partnership

- financial statements and tax returns for several years

- details of life insurance policies

The Estate Planning Process

SETTING OBJECTIVES

The starting point for any estate plan is to determine your objectives. You need to know where you want to go before you can develop a plan to get there. As the planning process unfolds, it will become clear what you can and cannot do. It will also become clear that you may need to modify some of your objectives. But you should start with a general idea of what you want to do.

The first objective of most estate plans is to provide adequate cash flow to your spouse or any dependents. Other common objectives are to maintain family ownership of a particular asset such as a family business or a woodlot, or to have the ecological features of the woodlot preserved by donating it to, or granting an easement to, a conservation authority.

Most people are concerned that they treat their children equitably, or fairly. Equitably does not necessarily mean equally. You do not have to subdivide your woodlot so each of three children gets a small woodlot of their own. And, it makes little sense to transfer a woodlot to a child who has no interest in managing it - especially if another child does. Equitable treatment might involve leaving the woodlot to one child and cash or life insurance to another.

List your estate planning objectives below:

1.

2.

3.

4.

LISTING ASSETS

LISTING ASSETS

To plan your estate you have to know what it will consist of. You need to make a list of all of your assets. Some things, such as household effects, can be grouped by type. But any asset that might be disposed of individually should be listed individually. A woodlot, for example, would be listed individually.

As well as identifying the assets themselves, you need to estimate the fair market value of each one. In some cases it is worth getting formal valuations or appraisals but in many others you can make a reasonable estimate yourself. Knowing the value of your assets makes an even-handed distribution of your estate easier. It also makes it easier to estimate the taxes payable.

It is important to list the original cost of the assets. This is used to calculate the tax liability. This information can be difficult to find, so the estate planning process is a good opportunity to create an accessible record.

Listing Liabilities

Your estate consists of your assets minus your liabilities. For older woodlot owners, taxes may be the only significant liability, but, for younger people, that may not be the case. They may have mortgages on land, or still owe money on equipment. Part of the process of planning your estate is to develop a plan to deal with your liabilities at death.

Developing and Implementing the Plan

With this information, you are ready to develop a working plan. Modify your objectives as it becomes clear what is practical and rework the plan until it meets your needs and wishes.

Information about things to consider when planning your future can be found in Lessons Two, Three and Four. You should refer to this information when developing your plan.

Implementing the plan often just requires a fairly simple will. More complex situations might require the formation of trusts or corporations, reorganizing existing corporations, acquiring life insurance and so on.

It is important to periodically review your plan, as family situations, assets held, and objectives change over the years.

Module 10b - Lesson Five Quiz

| Questions: | 5 |

| Attempts allowed: | Unlimited |

| Available: | Always |

| Pass rate: | 75 % |

| Backwards navigation: | Allowed |

Lesson Six - Estate Planning Tools

WILLS

Your will is the basic document in estate planning. The will determines how the estate will be distributed. In it, you can direct that a specific property (including a woodlot, a favorite fishing rod or a specific amount of cash) go to a certain person. The will also determines the distribution of the rest of your estate - the residue that is left after specific bequests have been dealt with.

More complex wills can provide for the establishment of various trusts and may give very specific direction as to the disposition of assets. That is, your will may specify exactly how and when your assets will be disposed of, who gets them, and under what conditions.

In your will you appoint an executor to manage your estate. You can have co-executors if you feel more than one person is required to carry out your wishes. An executor is generally a family member, but can be a friend, a lawyer or a trust company. Being an executor is a serious responsibility so you should choose yours carefully, and you must be sure they are willing to accept the appointment. The will should give the executor the power to make any income tax elections (choices) that they deem advisable.

Your spouse has an interest in all of the family’s assets under the Matrimonial Property Act. She or he is entitled to enforce the scheme of distribution of property under the Act rather than following the terms of the will. In other words, what you put in your will may be over-ridden by the rules of this Act, unless a marriage contract is in place. So it is important to involve your spouse in the whole estate planning process.

If you die without a will, or intestate, your estate will be distributed according to a statutory plan. If you are survived by a spouse, the first $50,000 of your estate goes to the spouse. If your spouse and one child survive you, the spouse and child would share equally in any part of the estate over $50,000. If two or more children and a spouse survive you, one-third of the assets over $50,000 go to the spouse and two-thirds to the children. If there is no spouse the estate is split equally among the children. This may not be what you wish; the cost of administration of the estate increases; and it may cost more in income tax in the event of death without a will. As such planning should include everyone who might be affected by the provisions of your will.

You can write a will on a piece of paper or you can buy a kit that shows you what to do. However most lawyers charge fairly modest fees for a simple will, and it is probably worth the cost to be sure it is done right.

Trusts

A trust is a relationship where one person (the trustee) holds property for the benefit of another person (the beneficiary). There can be more than one trustee and/or more than one beneficiary.

A trust is created by a person called the settlor. The settlor transfers property to the trust by means of a trust agreement. The trust agreement governs how the trust will operate, including how income and capital will be distributed. Each trust agreement is unique and this provides quite a bit of flexibility. The beneficiary of a trust owns the trust but does not manage it.

A testamentary trust is one that arises on and as a consequence of a person’s death. These trusts receive special tax treatment including a non-calendar year end, no installments, and graduated tax rates. Testamentary trusts are generally created under the terms of a person’s will.

A discretionary family trust is an “inter vivos” trust, which means it is created during the lifetime of the person who contributes property to the trust. This form of trust is generally used in effecting an estate freeze. The beneficiaries are primarily the members of one family (including by marriage), the distribution of trust income and/or capital is within the complete discretion of the trustees, and the trust property often consists of shares of one or more private companies.

The benefits of a trust can include income splitting with family members, access to multiple capital gains exemptions, deferring capital gains (otherwise resulting from deemed disposition) until death of spouse, access to multiple marginal taxation rates (testamentary trusts only), creditor protection, and separate control from beneficial owners.

Trusts are used in specific situations, such as when transferring property to a minor child. A trust is often used to manage an investment portfolio for the benefit of a spouse or child who lacks financial skills or responsibility. Another use of a trust would be to transfer a woodlot to children who are not yet ready to manage it.

The drawback of using a trust is that the transfer of property to the trust is a disposition of property and may create some immediate tax liability. This is something you can discuss further with your professional advisor.

Another particular type of trust is referred to in the Income Tax Act as a spousal trust. A spousal trust is one where no one but your spouse may benefit from the income or capital of the trust during the spouse’s lifetime. When the spouse dies, the remaining capital of the trust is distributed to the other beneficiaries, usually your children.

A spousal trust is used to provide income for the spouse to live on, while passing the capital (the original money or other assets in the trust) on to the next generation.

The Taxation of Capital Gains

A capital gain (or loss) occurs when a taxpayer disposes of a capital property. A disposition includes a sale, a gift or any other transaction where the “beneficial ownership” of the property changes. If you give your son your house, he takes on the beneficial ownership of the house, for example.

There are also a number of situations where the Income Tax Act deems that a disposition has taken place. That is, there are times when it is assumed, or deemed, you have disposed of your property. For estate planning purposes, the most important of these is that you are deemed to have disposed of all of your property when you die.

All disposals have proceeds of disposition or deemed proceeds of disposition. Generally, this is the money that was received for the property disposed of, usually simply the sale price of a property that has been sold. The proceeds can be zero, as when a property is destroyed or a debt goes bad.

Exchanges of property will produce proceeds of disposition. If you exchange properties with another person you will have proceeds of disposition equal to the fair market value of the property you receive. That is, if you exchange your woodlot for your friend’s house, which is worth $80,000, you will have proceeds of disposition of $80,000.

To determine the amount of a capital gain or loss, you take the proceeds of disposition and subtract from it the adjusted cost base of the property and any costs of disposition (legal fees, real estate commissions, and so on). There can be a number of complex technical adjustments, but in most cases the adjusted cost base of a property is simply its original purchase price.

There are two important exceptions to this rule. The first is a property that has been inherited. As we noted above, if a parent has left you a property in their will, they are deemed to have disposed of that property for proceeds equal to the fair market value of the property at the time. Their deemed proceeds become your deemed cost.

The other exception is a property that you owned on December 31, 1971. This was the day before capital gains became taxable in Canada and is referred to as Valuation Day or V-Day. There are two ways to calculate the adjusted cost base of a property owned on V-Day.

The basic way is by using the median rule. Using this method you find the adjusted cost base by working out which of these three amounts – the cost, the proceeds of disposition, or the fair market value on Valuation Day – has a value that falls in between the other two – this is the median. Usually this will work out to be the V-Day value. The other method (which most people use) is to elect (choose) to use the V-Day value – that is, the value from December 31, 1971.

Only one-half of a capital gain is taxable (for gains acquired after October 18, 2000). This taxable capital gain is included with your other income and taxed at your marginal tax rate. There is no specific “Capital Gains Tax.”

If the adjusted cost base plus the costs of disposition exceed the proceeds of disposition, then there is a capital loss. The allowable capital loss is one-half of the loss. Gains and losses are netted - or offset - against each other for the year. If there is a net loss, it can be carried back one year and forward indefinitely. A capital loss can only be deducted against capital gains.

Your principal residence is a special type of capital property. It includes your house plus one acre, unless you can demonstrate that more land is required for the use and enjoyment of the property. An example of a need for more land would be a zoning by-law that requires a minimum lot size. A gain on the disposition of your principal residence is not taxable. This is true even for any gain that might result from a deemed disposition on death.

Here are two examples of how the capital gains rules work.

Example 1

Assume that you purchased a woodlot in 1965 for $3,000. At December 31, 1971, it was worth $5,000. In 2008 you sold it for $75,000 and paid a real estate commission of $4,000 on the sale.

Your proceeds of disposition would be the sale price of $75,000. There are two ways to arrive at your adjusted costs base.

By the median rule method, the adjusted cost base would be the median (middle) amount of the cost of $3,000, the V-Day value of $5,000, and the proceeds of disposition of $75,000 (in this case it is the V-Day value of $5,000).

By the V-Day value method the adjusted cost base would simply be the V-Day value of $5,000.

In our example, the two methods produce the same result; an adjusted cost base of $5,000 and a gain of $70,000. From the above result, we subtract our cost if disposition, the commission of $4,000. This leaves us with a capital gain of $71,000. The taxable capital gain included in your income is 50% of this or $35,500.

Example 2

Assume a woodlot was purchased in 1980 for $10,000 and today is worth $80,000. You decide to give the woodlot to one of your children. Your proceeds of disposition will be the fair market value of $80,000. Your adjusted cost base is the original purchase price of $10,000. As there are no costs of disposition on the transaction, your capital gain is $70,000. And your taxable capital gain is 50% of that or $35,000.

Dealing at Arm’s Length

The Income Tax Act refers many times to dealing at arm’s length. People deal at arm’s length when they have separate and opposing economic interests. The Income Tax Act deems (assumes) that related persons do not deal at arm’s length. Related persons are your parents, children, spouse, in-laws and any corporation that you or they control. Unrelated persons may not be dealing at arm’s length, but this is dependent on the facts of the situation.

The importance of the concept of arm’s length is that transactions between persons not dealing at arm’s length are deemed to take place at fair market value rather than the notional transaction price. The effect of this is that if you leave your woodlot to your children, you will be deemed to have disposed of it for its fair market value.

Spousal Rollovers

The general rule is that, when you die, you are deemed to have disposed of all of your property at its fair market value – except for property that passes to your spouse or to a spousal trust. This property is deemed to be disposed of at your adjusted cost base. You should note that this transaction is not tax-free, but rather tax-deferred, as tax will be payable when the property is later disposed of by your spouse.

If you transferred property to your spouse during your lifetime, it is treated the same way. It is deemed to be disposed of at your adjusted cost base. Complex rules known as attribution rules prevent the transfer of income and capital gains between spouses. These are best explained by a tax specialist, but here is a simple example.

If your woodlot cost $7,000, for example, and is now worth $55,000 you could transfer it to your spouse with no immediate tax cost. You would be deemed to have disposed of the woodlot for $7,000 so you would have no gain or loss. Your spouse would be deemed to have a cost of $7,000. If your spouse then sold the woodlot for $55,000, there would be a $48,000 capital gain of which one-half ($24,000) would be taxable.

If you had transferred the woodlot to your spouse during your lifetime, the taxable capital gain would be included in your income. If the actual sale takes place after your death, the gain will be included in your spouse’s income – regardless of whether the property passed to your spouse during your lifetime or on your death.

Your executor can elect out of the adjusted cost base rule and have property deemed to be disposed of at fair market value. This can be useful in some situations – for example, when there are unused capital losses.

Unused capital losses can only be applied against capital gains. If the property passes to your spouse under the normal adjusted cost base rule, there will be no capital gain and your spouse will be subject to a larger capital gain when he or she disposes of the property.

Life Insurance

Life insurance can serve a number of purposes in estate planning. When you pass on, it can provide cash flow to allow your spouse and dependents to maintain their lifestyle while they are still young. It can provide ready cash to pay estate liabilities – you may have significant liabilities that will need to be met from estate funds. Later on, it can provide the cash to pay taxes rather than forcing your survivors to sell a property you wish to remain in the family.

Finally, many people simply want to leave something to their children. Life insurance is a way for you to save up this inheritance and be sure that it will be paid if you die prematurely.

All life insurance policies have a beneficiary or beneficiaries. Usually the beneficiary is a specific person or persons, but it can also be your estate. If it is your estate, control of the proceeds of the policy is dealt with by your executor.

Module 10b - Lesson Six Quiz

| Questions: | 9 |

| Attempts allowed: | Unlimited |

| Available: | Always |

| Pass rate: | 75 % |

| Backwards navigation: | Allowed |

Lesson Seven - Transfer of Your Woodlot/Succession Planning

General rule - sale at fair market value

As we have already mentioned, the general rule is that if you sell, gift or transfer your woodlot, it is deemed to have taken place at fair market value. The difference between the fair market value and the adjusted cost base is taxable as a capital gain, with the exception of transfer to your spouse as discussed earlier. This could result in large amounts of tax payable and may even require premature harvesting of all or part of the woodlot in order to obtain enough cash to pay the tax liability.

Farm Property